Glossary of Abbreviations

|

ABA |

American Bar Association |

|

ASF |

Lawyers without Borders (Avocats sans Frontières) |

|

CMO |

Operational Military Court (Cour Militaire Opérationnelle) |

|

CNDP |

National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès National pour la Défense du Peuple) |

|

Congo |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

|

FARDC |

Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo) |

|

FDLR |

Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Rwanda) |

|

ICC |

International Criminal Court |

|

ICTR |

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda |

|

ICTY |

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia |

|

M23 |

March 23rd Movement |

|

MONUSCO |

United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Mission de l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation en RD Congo) |

|

NGO |

Non-governmental Organization |

|

OTP |

Office of the Prosecutor (of the International Criminal Court) |

|

UNDP |

United Nations Development Program |

|

UNJHRO |

United Nations Joint Human Rights Office |

|

UNPSCs |

United Nations Prosecution Support Cells |

Summary

“When the court arrived in Minova, I felt a bit happy. I thought, ‘Finally, here is someone to listen to us and the horrible things that happened to us.’… But the judgment [it handed down], it is a lie. We were hurt. Where are they, then, those who hurt us? I am ready to continue and go anywhere for justice to be done.”

—Rape victim who participated in the Minova trial, Minova, May 2014

In November 2012, Congolese army soldiers retreated from the advancing M23 rebel group that had taken the strategic city of Goma in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. They redeployed in Minova, a market town on the shores of Lake Kivu. En route and in Minova and surrounding communities, the soldiers engaged in a 10-day frenzy of destruction: looting homes, razing shops and shelters in camps for displaced people, and raping at least 76 women and girls.

The violence from November 20 to November 30 prompted a public outcry in Congo and beyond. Congolese authorities, who had announced a “zero tolerance” policy toward serious crimes—including sexual violence—now faced intense international pressure to bring the perpetrators to justice.

One year later, in December 2013, 14 officers and 25 rank-and-file soldiers of the Congolese army were put on trial in Goma, the capital of North Kivu province, on various charges, including the war crimes of rape and pillage, rape as an ordinary crime, and various military offenses. In more than 40 days of hearings over five months, close to 75 of the 1,016 people who joined the case as victim participants gave testimony, in addition to the defendants and other witnesses. The court held 10 days of hearings in Minova, thus bringing justice closer to those affected by the crimes.

International and national non-governmental organizations viewed the Minova trial as a test case for the Congolese justice system and its ability to hold perpetrators of grave human rights abuses to account. Many hoped it would demonstrate a real commitment by Congolese authorities, including the military, to ensure that justice would be served for grave international crimes.

The trial verdict, rendered by a local military court in Goma on May 5, 2014, quashed these hopes. Of the 39 accused, only two of the low-ranking soldiers were convicted of one individual rape each. The high-level commanders with overall responsibility for the troops in Minova were never charged; those lower-ranking officers who were charged were all acquitted. A number of soldiers were convicted of the war crime of pillage, despite an obvious lack of evidence against them.

Based on more than 65 interviews and a review of court documents, this report offers insight into the inner workings of the Congolese military justice system in the Minova case. It provides a detailed analysis of the investigation and trial—examining what went right and what did not.

Fair and impartial justice does not mean securing convictions at all cost. It is important that the military court acquitted those against whom it did not find sufficient evidence of wrongdoing. Yet, the Minova investigation and trial failed to establish what exactly happened in Minova, to identify those who were responsible for the crimes, and to bring justice to the victims.

Building on the Minova trial as an example, the report identifies reforms to the national justice system that are needed to strengthen the fight against impunity for international crimes in Congo. These include strengthening the legislative framework; increasing the specialized expertise of the justice system to handle atrocity crimes, including through the creation of a specialized investigation cell; and bolstering the independence of both the civilian and military justice systems. The government’s proposal to establish an internationalized justice mechanism within national courts remains of critical importance.

The Congolese government has legal obligations under international law to ensure that those responsible for sexual violence and other grave international crimes such as murder, pillage, torture, and the use of child soldiers are investigated and prosecuted in fair and credible trials.

There has been some progress in Congo over the past 10 years, with about 30 cases involving war crimes and crimes against humanity charges tried before local military courts. However, the vast majority of atrocities committed in Congo by members of armed groups and national armed forces during the fighting over the past two decades remain unpunished.

* * *

There were positive aspects to the Minova trial, which reflect some of the progress and experience amassed in Congo over the past decade in rendering justice for grave international crimes.

For example, the government affirmed its commitment to justice and made funds available for the trial, during which all parties had legal representation. Military judges on the bench directed the hearings effectively. Challenges, such as protecting or organizing victim and witness participation, were well addressed. Military prosecutors and judges directly applied provisions of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), notably with regard to the legal theory of command responsibility and protection measures that are not available under Congolese law. Diplomatic pressure helped to ensure the case went to trial: the United Nations, for example, which had supported Congolese troops in military operations, threatened to withdraw military support unless those responsible for crimes were arrested and brought to justice.

There were also unique challenges present in the Minova case. Different army battalions and thousands of soldiers were in Minova at the time of the crimes, making it difficult to identify individual perpetrators. Commanders were replaced just before the retreat towards Minova and individual soldiers were in disarray, outside their regular units. No evidence emerged that soldiers had been ordered or encouraged to rape and pillage, but commanders failed to control their troops and to prevent, stop, or punish crimes. In addition, the timing of the investigation and trial was politically difficult: the conflict with the M23 continued as investigations were underway and many believed that the trial would harm soldier morale. In December 2013, when the case was rushed to trial, largely due to international pressure, the high-level commanders present in Minova in 2012 were already being touted as national heroes for having defeated the abusive M23.

Nonetheless, Human Rights Watch has identified three key sets of problems in the case:

- Several prosecution offices were involved in the investigation and prosecution of the case, creating confusion. There was no investigation plan or strategy to tackle such a mass crime scene. Lack of expertise and diligence contributed to the poor quality of the investigation and a weak prosecution file;

- The rights of defendants to a fair and impartial trial were compromised. In particular, some rank-and-file soldiers suffered from weak legal representation and were convicted for the war crime of pillage and sentenced to up to 20 years in prison despite a lack of evidence. Congolese military law does not allow the right to appeal before the type of military court that heard the Minova trial; and

- The selection of accused by military prosecutors raised concerns about the political will of the armed forces to allow all those responsible for the numerous crimes in Minova to be prosecuted. Some of the officers indicted appeared to be uninvolved scapegoats for other officers with genuine command roles. There did not seem to be any willingness to seriously investigate the responsibility of certain suspects beyond field commanders, notably high-level officers who were present in Minova and may have had command responsibility.

These three failings exemplify some of the major problems that hamper accountability for serious crimes in Congo. These difficulties remain unaddressed despite years of international assistance and training of military justice officials aimed at strengthening the capacity of the national judicial system to handle grave international crimes, and promoting accountability before national courts to complement work of the ICC.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Congolese government and parliament to move forward with the proposal to establish a temporary internationalized justice mechanism involving both national and international judicial staff within the national justice system to investigate grave international crimes. Although two draft laws have faced some political resistance, such an internationalized mechanism remains critical to bolster specialized expertise and shield proceedings from interference.

Providing justice is a legal obligation of states toward individuals who have suffered grave crimes. In addition, credible, fair, and impartial trials for war crimes and crimes against humanity can be important in fostering longer term peace and stability by signaling that atrocities will not be tolerated.

National trials such as the one held to prosecute the Minova crimes do the opposite—discouraging victims and entrenching the perception that justice is arbitrary and that high-level commanders are protected no matter what happens. Congolese authorities and their international partners should urgently work to meaningfully address the challenges that continue to hinder effective justice in Congo.

Recommendations

To the Congolese Government

Seek New Investigations into Additional Minova Crimes

- Direct the office of the military prosecutor to conduct new investigations into possible crimes committed in Minova and surrounding villages that have not been prosecuted previously, in accordance with the prohibition against “double jeopardy,” and with a view to holding accountable those most responsible for the crimes.

Bolster Accountability through an Internationalized Justice Mechanism

- Work to review and pass a law establishing an internationalized justice mechanism within national courts to investigate grave international crimes.

Strengthen the Quality of National Investigations and Prosecutions

- Draft a national criminal policy on prosecutions of grave international crimes that highlights objectives and priority needs in this field, details the government’s own contribution to strengthen accountability, and serves as a basis for consultations with international donors;

- Create a specialized investigation cell of military investigators and prosecutors with specialized training in the investigation and prosecution of grave international crimes, including gender-based crimes and sexual violence, to be deployed in provinces where these crimes are most often adjudicated; and

- Work to pass legislation implementing the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) into Congolese law to improve the national legislative framework to prosecute grave international crimes.

Bolster Independence of Prosecutors and Judges across the Justice System

- Contribute to creating an enabling climate for the fight against impunity by making public and private statements reaffirming the government’s support for independent and impartial investigations into grave international crimes, irrespective of the identity of the suspects;

- Investigate and impose sanctions against political or army officials who try to interfere with the work of judges and prosecutors dealing with grave international crimes;

- Take measures to tackle corruption among officials in the military and civilian justice systems, including by ensuring appropriate salaries and sanctioning corrupt behavior; and

- Given concerns about trials concerning grave international crimes before the military justice system, transfer jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide from the military justice system to civilian courts irrespective of the perpetrator, while maintaining some involvement of military justice officials.

Improve Fair Trial Rights for Defendants

- Draft and work to pass a law specifying that indigent defendants have a right to free legal assistance paid by the state. Ensure that such pro bono lawyers are exempted from paying judicial fees to make copies of criminal files;

- Strengthen legal assistance for defendants in cases of grave international crimes before Congolese courts, by ensuring that suspects have access to a lawyer at the early phases of the investigation, including all their interrogations by investigators. Work with international partners to ensure that lawyers receive the necessary training and assistance to competently represent persons accused of grave international crimes; and

- Ensure, in accordance with the Congolese Constitution, that the right to appeal is available for all and before all jurisdictions in Congo. To that effect, present again to parliament the draft law creating a right to appeal before operational military courts and create an appeal for those who enjoy “privileges of jurisdiction.”

Improve Protection, Victims’ Rights

- Draft and work to pass a law on the protection of victims and witnesses that details protection measures available inside and outside the courtroom, and that is consistent with defendants’ rights to a fair trial. Ensure that women’s groups are consulted and able to participate in the drafting process so that their different protection needs are adequately included;

- Work with the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo (MONUSCO) and other international partners to set up an independent national protection program for victims and witnesses of grave international crimes; and

- Immediately pay reparations ordered against the state by criminal courts in cases of grave international crimes and sexual violence. Start consultations to design an effective and sustainable reparations scheme for grave international crimes.

To the Personal Representative of the Congolese Head of State in Charge of the Fight against Sexual Violence and the Recruitment of Children

- Collaborate with the minister of justice to design a plan of action to improve the capacity of the national judicial system to handle complex cases involving sexual violence, including by ensuring that investigators receive adequate training in conducting investigations into international crimes and sexual violence and by creating a trained pool of female military investigators, magistrates, and prosecutors with expertise in investigating and adjudicating grave international crimes;

- Ensure that a prosecutorial strategy on the fight against impunity includes specific incidents of mass sexual violence; and

- Together with the Ministry of Justice, help initiate broad consultations on reparations for victims of grave international crimes, ensuring that victims in particular, but also reparations experts and victims associations have an opportunity to provide input.

To the Congolese Defense Minister

- Investigate and sanction attempted interference by the military command into investigations and trials of grave international crimes.

To the Congolese Parliament

- Pass legislation implementing the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court into Congolese law;

- When it is submitted again by the government, pass legislation creating an internationalized justice mechanism in the national judicial system; and

- Pass legislation on the protection of victims and witnesses that details protection measures available inside and outside the courtroom and creates an independent protection program.

To the Military General Prosecutor’s Office and the High Military Court

- Support the government’s proposal to create an internationalized justice mechanism for the prosecution of grave international crimes;

- Support the creation of a specialized investigation cell focusing on grave international crimes;

- Refrain from intervening in cases handled by prosecutors before lower courts, unless strictly and legally necessary; and

- Request cooperation from the ICC in relevant national cases, using article 93(1) of the Rome Statute.

To the Military Prosecution Offices in North Kivu and South Kivu, and Other Provinces where Grave International Crimes are Committed

- Establish a clear investigative plan and prosecution strategy when opening a complex case involving grave crimes, and identify benchmarks to measure progress in building the case;

- Strengthen collaboration with experts from the UN Prosecution Support Cells, by involving them at the onset of investigations into specific cases, when the investigative and prosecutorial plans are designed; and

- Denounce attempted interference in cases of grave international crimes by political authorities or the military hierarchy.

To the United Nations, Intergovernmental and Governmental Donors and Partners, including MONUSCO, the United Nations Development Program, the European Union, Belgium, France, South Africa, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States

- Call for new investigations into Minova crimes that have not been prosecuted previously, in accordance with the prohibition against “double jeopardy,” and support national efforts to that effect;

- Support the government’s proposal to establish an internationalized justice mechanism in the national judicial system as an effort to improve the capacity and independence of the national judicial system in prosecuting grave international crimes;

- Increase public and private statements about the importance of accountability for grave international crimes, use diplomatic leverage to urge that investigations in specific cases of serious international crimes are progressing, and press the Congolese government to ensure respect for the independence of prosecutors and judges.

- Call for progress on necessary legislative reforms, including adoption of the ICC implementing legislation;

- Continue the use of coordination mechanisms in Bukavu and Goma to coordinate financial and logistical support to specific international crimes cases; see that these mechanisms continue to be used to press for real progress in open investigations into war crimes and crimes against humanity;

- Improve coordination on projects aimed at strengthening national prosecutions of serious international crimes at the conceptualization phase; establish a working group on complementarity in Kinshasa and engage the government on drafting a national criminal policy on accountability for grave international crimes;

- On the basis of the independent evaluations of the performance and impact of the UN Prosecution Support Cells, identify necessary adjustments and finance such improvements, including the hiring of individuals with proven expertise and experience in investigating and prosecuting grave international crimes, gender experts, and experts with specialized training in gender-based crimes and sexual violence; and

- Support specialized capacity-building for investigators and prosecutors in the field of investigations and prosecution techniques specific to grave international crimes, including the investigation of sexual violence, gender-based crimes, and crimes perpetrated against women.

To MONUSCO

- Continue crucial support to national investigations of grave international crimes in Congo, including through UN Joint Human Rights Office independent investigations and public reports; the deployment of joint investigation teams; the UN Prosecution Support Cells; logistical, security, and protection assistance to national justice actors; arrest of suspects; pressure for progress in open investigations, and use of conditionality in application of the UN Human Rights Due Diligence Policy; and

- Improve the coordination and complementarity of the UN Joint Human Rights Office and the UN Prosecution Support Cells in assisting the national justice system with the investigation and prosecution of grave international crimes to avoid duplications and make the most of respective strengths.

To the Justice and Corrections Unit and the UN Prosecution Support Cells

- Ensure that international experts with appropriate experience in war crimes cases, gender, gender-based crimes, and crimes perpetrated against women, are hired in the UN Prosecution Support Cells, including by increasing the number of positions dedicated to independent experts, as opposed to officials seconded by governments; and by encouraging international institutions, such as the ICC, other international tribunals, and UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Commissions of Inquiry to allow their staff to participate in the Prosecution Support Cells while on limited, reimbursable leave;

- Implement a more proactive approach to the UN Prosecution Support Cell mandate, notably by seeking more direct involvement in specific cases under investigation from the outset;

- Monitor blockages or interference from the political or military hierarchy in cases of grave international crimes, press judicial staff to use national administrative and judicial mechanisms to report this interference, and report interference to the hierarchy within MONUSCO, so that it can also be brought up with authorities in Kinshasa; and

- Produce a yearly public report on activities undertaken, providing details on the specific cases worked on and the type of technical advice, training, and logistical support provided.

To the International Criminal Court

- Continue investigations in Congo, focusing on cases that cannot be investigated and prosecuted fairly and credibly before national courts;

- Upon creation of an internationalized justice mechanism, discuss a division of labor, the sharing of information and expertise, and cooperation between the two jurisdictions; and

- Adopt an institution-wide strategy on positive complementarity, as well as a Congo-specific strategy highlighting measures that the registry and the Office of the Prosecutor can take to encourage national prosecutions of grave international crimes.

Methodology

This report is based on 68 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch between May 2014 and June 2015. Shortly after the conclusion of the Minova trial on May 5, 2014, Human Rights Watch carried out research in Goma, Bukavu, and Minova in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Human Rights Watch interviewed 28 people during that mission, including Congolese judicial officials, defense and victims’ lawyers and other legal practitioners, representatives of Congolese and international non-governmental organizations, diplomats, United Nations officials, and victims of human rights abuses who had been involved in or closely followed the Minova trial.

Between July 2014 and June 2015, Human Rights Watch conducted additional interviews in person in Kinshasa, the capital of Congo, as well as by telephone and email, with UN officials, International Criminal Court officials, military justice officials, individuals with expertise in the investigation and prosecution of grave international crimes, Congolese government officials, and Congolese and international experts on the justice system in Congo. The reactions of Congolese officials to our findings have been integrated in the report. Most interviews were conducted in person and in French or English. Interviews with victims were carried out in private and in Swahili with the assistance of an interpreter. No incentives were provided to individuals in exchange for their interviews.

Human Rights Watch worked with a Congolese human rights activist who monitored all sessions of the Minova trial. Staff also obtained copies of and analyzed several public court documents related to the case, including the indictments, handwritten official records of the hearings, closing briefs presented by the lawyers of the victims and defendants, and the judgment.

Many individuals interviewed did not wish to be cited by name given the sensitivity of some of the issues covered in this report. To respect the confidentiality of these sources, we have used generic descriptions of the positions held by many of the interviewees.

I. Background

Since the early 1990s, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo has been wracked by a series of regional and local armed conflicts. Rebel movements have emerged repeatedly, often with the support of neighboring countries. Dozens of armed groups still operate in Congo today. Both these armed groups and the regular Congolese army forces battling them have preyed on civilians, committing grave violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. These include ethnic killings, pillage, mass rape and other forms of sexual violence, burning and destroying homes, and recruiting and using child soldiers.[1]

For a long time, the Congolese government implemented a policy of integrating abusive rebel leaders into the regular army instead of holding them accountable for serious human rights abuses.[2] This approach has encouraged the emergence of new rebel groups and further abuses and violence.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) opened investigations in Congo in 2004 and has handled a small number of cases related to international crimes in Congo. In recent years, Congolese authorities, with the support of international partners, have taken significant steps at the national level to bring to justice those who commit these grave crimes. The Minova trial is one such case handled by national military courts in Congo.

Minova and Surrounding Villages, November 2012

In April 2012, an armed conflict erupted in eastern Congo’s North Kivu province between the Congolese army and a new rebel movement, the M23.[3] The M23 was formed in April 2012 after a mutiny by former members of a previous rebel group, the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP). Most of the group’s fighters had integrated into the Congolese armed forces in 2009.

With significant support from senior Rwandan military officials, the M23 gained control of much of Rutshuru and Nyiragongo territories in North Kivu by July 2012.[4] On November 20, 2012, the M23 seized the eastern city of Goma.[5]

Goma’s fall to a rebel group was significant for the Congolese population and army, reminiscent of Rwandan and Ugandan occupation of parts of eastern Congo in the 1990s. Goma’s fall had a deep impact on troop morale. After the M23 occupied Goma, several Congolese army battalions were given the order to retreat to Minova, a town 50 kilometers away, in order to reorganize and prepare next steps.

On the way to Minova, once there, and in surrounding communities, soldiers committed widespread looting of homes and mass rapes of women and girls. Human Rights Watch documented at least 76 cases of rape of women and girls by soldiers from November 20 to November 30 in Minova and the nearby villages of Bwisha, Buganga, Mubimbi, Kishinji, Katolo, Ruchunda, and Kalungu.[6] In a report documenting grave international crimes committed by the Congolese army and M23 fighters in Goma, Sake, and Minova at the end of 2012, the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office documented 135 cases of sexual violence committed by soldiers in the same 10 days, namely rapes against 97 women and 33 girls ages 6 to 17, and five attempted rapes.[7] Most crimes were reported to have happened on November 22-23.

Many more women and girls may have been raped but did not speak up due to stigmatization and shame associated with rape in Congo. Several women described to Human Rights Watch a recurrent pattern of attack: soldiers in official army uniform forced their way into their homes at night, pointed guns at them, and demanded money. The soldiers then threatened to kill the women if they refused to have sex with them or if they screamed for help. Some women were raped by multiple assailants in front of their husbands and children. Other women were raped as they fled the M23 advance.

A 30-year-old mother of four from a village outside Minova told Human Rights Watch that she was preparing dinner on the evening of November 22 when she heard gunfire. Four uniformed soldiers entered her home and started looting it. They bound her husband’s hands and feet, then tied him to the door and beat him with the butt of their guns:

They said: “Give money. Give everything you have.” Then they all raped me. They said that if I resisted, they would kill me. The bedroom didn’t have a door, so [the children] could easily see what was happening. My husband has since abandoned me. He says he can’t stay with me because he saw how they raped me.[8]

Human Rights Watch also documented at least one killing of a young boy by a soldier. The UN Joint Human Rights Office documented extensive and systematic looting by soldiers in Minova and in at least eight surrounding villages, as well as in two camps for internally displaced persons in Mubimbi the night of November 22-23, and in Minova, the night of November 23-24, 2012.[9]

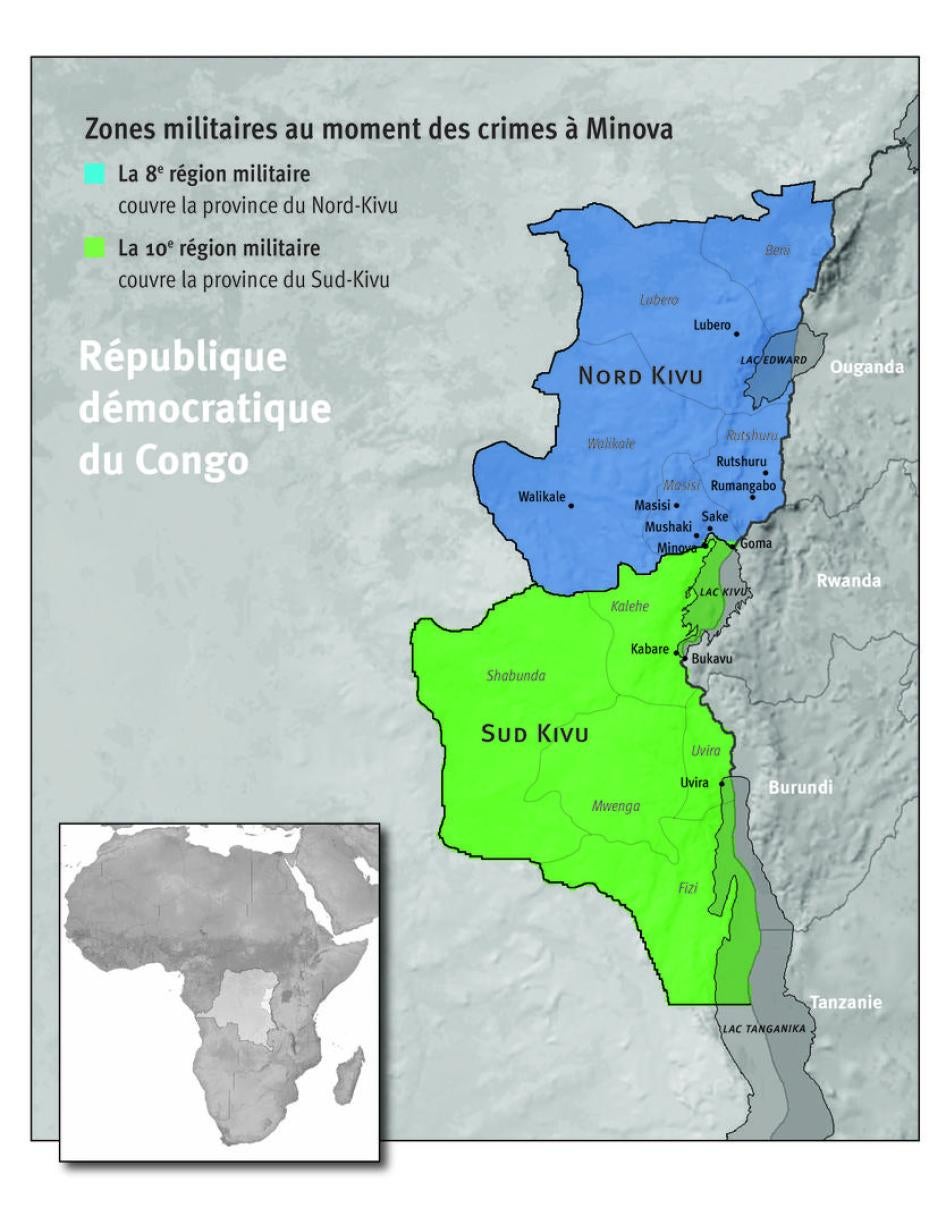

Several hundred soldiers were present in Minova in late November 2012.[10] The battalions that fought the M23 around Goma at the time—and which later retreated toward Minova—included the 802nd, 804th, 806th, and 810th Regiments and the 391st and 41st Commando Battalions from North Kivu’s 8th Military Region.[11]

The 1006th and 1008th Battalions from South Kivu’s 10th Military Region were also in the area, although the date of their arrival in Minova is not clear. Soldiers from the Republican Guard, which ensures presidential security, as well as a headquarters battalion from the 8th Military Region, the military police, and several senior officers were also present. The soldiers were new to the area and the attacks happened at night, making it especially difficult for victims to identify perpetrators.

Army officers and senior government officials said that soldiers were demoralized and angry after the loss of Goma and moved in a disorganized manner towards Minova and surrounding villages.[12] Restoring order after such a serious defeat and retreat was an arduous task. However, international criminal law required the commanders in charge of troops in November 2012 to take concrete and targeted measures to prevent, stop, and punish those responsible for the crimes.[13] As described later in this report, the Minova trial did not fully uncover what occurred in Minova, leaving many questions unanswered.

Minova Investigation and Trial

The UN peacekeeping mission in Congo, (MONUSCO), publicly denounced the abuses shortly after they had happened and called for an immediate investigation.[14] In the following weeks, the media reported that nine soldiers had been arrested in connection with the Minova events, two for rape and seven for pillage, although it turned out that several of them were not involved in the crimes and were later released.[15]

The investigation was complicated by the location of Minova, which lies at the border between South Kivu and North Kivu provinces and between the 10th and 8th Military Regions. Given the location of the town and the soldiers implicated in the crimes, the jurisdiction of both the South Kivu and North Kivu military prosecutors was at play.

The investigation was initially led by the South Kivu prosecution office, which conducted three short investigation missions to Minova in late December 2012 and in February 2013, organized with the support of international partners. In part due to growing international pressure on Congolese authorities regarding the case, the General Military Prosecution Office in Kinshasa sent a general military prosecutor to take over the investigation. He went to Goma and Minova in April 2013 and questioned suspects and senior army officers. No further investigative steps appear to have been taken after that.

The prosecutor of the North Kivu Operational Military Court (Cour militaire opérationnelle, CMO) eventually issued indictments on November 5, 2013 against 39 accused: 14 officers and 25 regular soldiers of the Congolese army.[16] All but one of the officers were charged with the war crimes of rape, pillage, and murder committed by troops under their control.[17] The soldiers faced various charges, including the war crimes of rape and pillage, rape as an ordinary crime, and military offenses.[18] Joining the case as victim participants were 1,016 victims.[19]

The North Kivu CMO, which heard the case, was established under the military judicial code by presidential decree in 2008 to prosecute violations committed by members of the armed forces during military operations in times of war. The UN and civil society organizations strongly resisted the use of the CMO for the Minova trial, notably because it does not allow appeals of judgments and there were concerns that it would be more prone to command interference than regular military courts.

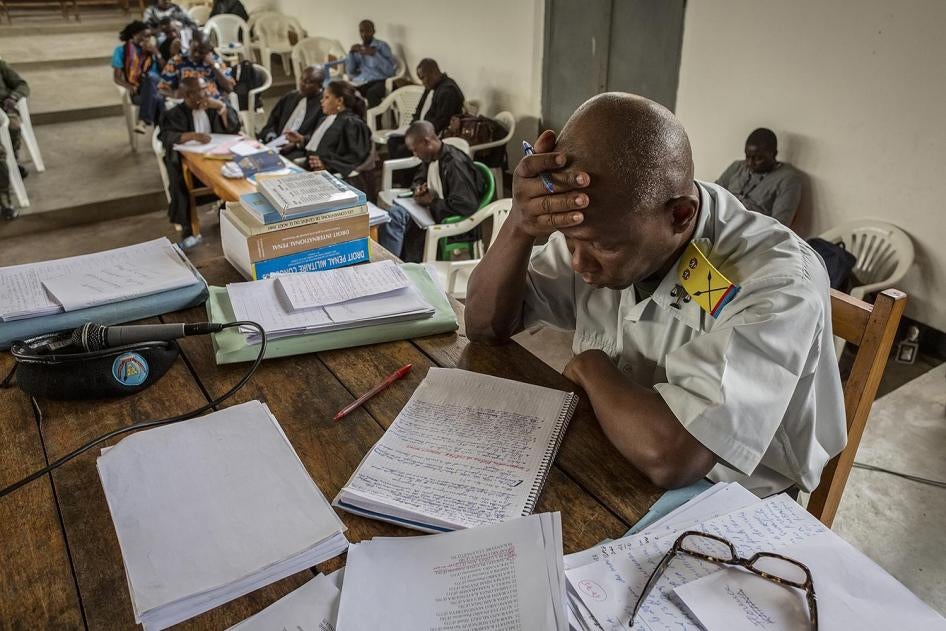

During the trial, 39 defendants, 15 witnesses (such as doctors, local chiefs and civil society representatives) and 76 victims-including 50 victims of rape and 26 of pillage—testified.[20]

On May 5, 2014, the CMO rendered its verdict:

- Of the defendants, two of the rank-and-file soldiers initially accused of rape as an ordinary crime were convicted, one for raping a girl as an ordinary crime and the other for rape as a war crime. They were sentenced to 20 years and life in prison respectively;

- All other regular soldiers were acquitted of the war crime of rape, but were convicted of other crimes including violating military instructions and the war crime of pillage, with sentences ranging between three and 10 years in prison;

- All the officers prosecuted on account of their responsibility as superiors were acquitted of all crimes; and

- The officer accused of being a direct perpetrator was acquitted of rape but found guilty of stealing a motorbike and sentenced to five years in prison.[21]

Victims and civil society activists reacted to the verdict with widespread disappointment.[22]

II. The Investigation and Prosecution

Our analysis of the Minova case found that the criminal investigation into the crimes was of poor quality, due largely to a lack of expertise and diligence on the part of the Congolese military investigators and prosecutors. This was despite the involvement of the UN Prosecution Support Cells that are mandated to assist national investigations and prosecutions of serious international crimes.

While Human Rights Watch could not review the evidence contained in the Minova file, which is confidential and restricted to the parties, we were able to interview individuals close to the case and to analyze public trial documents. The following observations are based on that material.

The investigations into the Minova crimes started late and took place under difficult circumstances. At the time of the withdrawal towards Minova, military justice officials usually based in Goma had fled the city and thus did not accompany the troops. This created a delay in the investigations.[23] The fighting with the M23 continued for several months after the Minova episode and the region remained highly militarized, which created a difficult security situation for victims and witnesses.[24]

At least five different military police and prosecution offices were involved in investigating and prosecuting the Minova case.[25] This appears to have created confusion in the investigations and made it difficult to have a coherent investigative and prosecutorial strategy.[26] For example, the military prosecutor who brought the case before the Operational Military Court, Col. Jean Baseleba bin Mateto, had not been involved in the investigations, which may have complicated his role at the trial.[27]

Lack of Investigative Plan to Tackle Mass Crimes

While some military investigators and magistrates, notably from South Kivu province, had previously worked on cases involving grave international crimes, others from North Kivu had not.[28] Since Minova is located in South Kivu province, military justice officials in Bukavu started the investigations. They focused on interviewing a large number of victims.[29] The interviews were conducted quickly and involved a short set of recurring questions such as “What is your name? What happened to you? Who attacked you? What did you lose? What are you expecting from justice?”[30]

The written notes of the victims’ statements were brief and failed to highlight other information that could have been important for the case. There were no details to help confirm the dates of the crimes, the troops involved, the injuries suffered, and a pattern of attacks.[31] According to one judicial official interviewed by Human Rights Watch after the trial: “The victims’ statements were like short identical forms; nobody checked the allegations.”[32] A victims’ lawyer said: “It was as if the military police had been in a rush to do the interviews quick—quick and leave.”[33]

Little or no effort was made to conduct in-depth analysis of the evidence collected. Very few interviews held jointly with victims and witnesses or defendants to resolve contradictory testimony were organized before the trial, which could have helped establish facts where testimonies conflicted.[34] The military investigators also did not include a map of Minova and surrounding villages, which would have helped judges visualize the location of the various troops and their movements.[35]

In April 2013, Gen. Timothée Mukunto Kiyana of the General Military Prosecution Office (Auditorat Général) in Kinshasa took over the investigation. He did not seem to take into account or build on the testimonies collected by the Bukavu prosecution office.[36] General Mukunto met with the commanders of the battalions identified in the UN Joint Human Rights Office report as being responsible for the crimes committed in the Minova area, in particular the 391st and 41st Commando Battalions, and demanded they give him the names of soldiers involved in the crimes.[37]

The commanders of these two battalions produced lists of soldiers absent from the roll calls that were conducted during the time in Minova.[38] The soldiers absent during the roll calls, together with their company and battalion commanders, were eventually charged and made up the majority of accused subsequently brought to trial.[39] For most of the soldiers named on these lists, Human Rights Watch is not aware of any further investigative steps taken to confirm whether they were indeed involved in the crimes of pillage and rape. It is also not clear to what extent other battalions present in Minova or surrounding villages–for example, Kalungu–were investigated.

The military prosecutor, Colonel Baseleba, tried to bring additional information or witnesses at trial, but the judges repeatedly reminded him that steps to corroborate information ought to have been taken before the trial.[40] After the trial, one judicial official involved in the proceedings commented:

In matters involving international crimes, it is imperative to better train those who conduct the investigations. If they conduct the investigations like they would for ordinary crimes, then they have not gone deep enough. Judicial police need to be trained so that they don’t hit so wide off the mark.[41]

Prosecution Errors

Several errors in the file also point to a lack of preparation or diligence by military prosecutors.

For example, five soldiers were sent to trial despite the fact that no information about them could be found in the investigation file.[42] The judges initially ordered that the five be released, but later it became clear that the prosecution had failed to obtain the transfer of their files from a garrison tribunal in Uvira, South Kivu, where the soldiers were first detained.[43] Their files were eventually added to the Minova case given that the accusations they faced were related to the events in Minova.[44] Two of these five accused are those who were convicted of rape in the Minova trial.[45]

In another example of prosecution error, one company commander, Capt. Byamungu Rusemasema, was indicted by mistake, since he did not hold the position of company commander as alleged by the prosecution at the time of the crimes in Minova. The prosecution did not try to reassess his potential role in the crimes and the CMO eventually decided it lacked jurisdiction over his case.[46]

Further, the indictments against the commanders, which are based on their “command responsibility” over soldiers accused of having directly committed the crimes, wrongly applied the legal theory for some of the crimes. For example, all commanders charged under command responsibility were charged with the war crime of murder, yet only one murder was discussed in the Minova case—that of a 14-year-old boy who was shot as he tried to resist a soldier stealing the family goat. The direct perpetrator, Cpl. Alphonse Magbo, was identified and charged in the case. But since he was a soldier of the 1008th Battalion of the 10th Military Region, he was not a subordinate of any of the indicted commanders.[47]

Finally, in his closing statement, the military prosecutor sought guilty verdicts against four defendants for crimes with which they had not been charged, adding to the confusion of the case.[48]

Difficulties in Establishing Sexual Violence

The two defendants convicted of rape in the Minova case were direct perpetrators who could be identified by their victims. One of the convicted soldiers, Second Lt. Sabwe Tshibanda, belonged to the 1007th Regiment of the 10th Military Region and was identified by the victim who remembered that the man who raped her was missing a thumb. The victim reported this fact together with the rape to the local priest the morning after, and he in turn informed a military commander present in the area. The soldier was arrested at the time and the victim identified him again in the courtroom during the Minova trial.

The other convicted soldier, Cpl. Kabiona Ruhingiza of the 8th Military Region, raped the 8-year-old daughter of a fellow soldier with whom he shared accommodation at a school in Minova. The perpetrator was caught while committing the crime by two other soldiers of his battalion and admitted the crime to his commander. The mother of the girl identified him during the trial.[49]

No other soldiers or commanders in the case were convicted for sexual violence in Minova and surrounding villages.

Some observers said that forensics evidence, notably DNA testing and medical certificates, could have made a difference in the Minova case.[50] The military justice and health systems in Congo currently do not have any DNA testing capacity. But given the number of soldiers present in Minova at the time of the crimes, the fact that they belonged to several different military regions, battalions, and companies, and the dispersal of victims, it seems that DNA testing would have been excessively difficult and expensive. While this investigative technique may potentially be helpful in other, more contained, cases, it is very costly and resource intensive.

Very few medical certificates of victims were presented in the Minova case.[51] Several medical certificate forms that currently exist for rape victims in hospitals and health centers in eastern Congo could be of more assistance in trials if they included additional forensic and narrative information, such as a description of the attack or information about other injuries sustained by the victim. This additional information could be helpful not only to strengthen the credibility of victim testimonies at a later phase, but also to elicit broader information that may help identify to which battalions the perpetrators belong and therefore the responsible commanders.[52]

One key difficulty in establishing responsibility for the mass rapes in the Minova case was due to the presence of multiple army units in the area at the same time. This made it difficult to identify individual perpetrators, their battalions, and in turn their commanders. Victims’ evidence was clear and consistent that their attackers were Congolese army soldiers, however. More work should have been done to analyze collated victims’ testimony in order to identify the dates and locations when spates of sexual violence attacks happened and to cross-check that information with troop movements. The responsibility of top military officers who bore overall responsibility for the Congolese army troops at the time of the Minova retreat (above the battalion level if specific battalions could not be identified) should also have been examined further.

Insufficient Support from UN Prosecution Support Cells

MONUSCO has a clear mandate to assist national investigations and prosecutions of grave international crimes.[53] Two MONUSCO components provide such support: the UN Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO) and the UN Prosecution Support Cells (UNPSCs).

UN Joint Human Rights Office

The UN Joint Human Rights Office organizes and financially supports investigative missions by so-called Joint Investigations Teams, made up of UN Joint Human Rights Office human rights investigators, Congolese investigators and prosecutors, as well as other international partners.[54]

These missions provide critical logistical support for national justice officials, especially in accessing remote locations. The presence of UN human rights investigators, who have often conducted their own investigations previously, can sometimes make victims and witnesses more comfortable speaking to justice officials.[55]

The UN Joint Human Rights Office also provides logistical assistance to investigations and trials and protection for victims, witnesses, and judicial actors. The office shares specific factual information and findings from their own investigations with the Congolese investigators and prosecutors, and it closely monitors and presses for progress in open cases.[56]

In the Minova case, the UN Joint Human Rights Office documented crimes allegedly committed in Minova and surrounding villages in November 2012 and published its findings in a report. It pressed the military justice system to open an investigation and facilitated investigation missions to Minova for the South Kivu military justice officials. The protection unit of the UN Joint Human Rights Office oversaw protection of victims and witnesses and security for judicial officials and the office collaborated with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to facilitate the participation of victims in the trial.[57]

UN Prosecution Support Cells

The UN Prosecution Support Cells, still relatively new, aim to improve the quality of national investigations and prosecutions of the most serious crimes by working alongside Congolese military investigators and prosecutors to provide training and technical advice when investigating these crimes.[58] They also help organize and coordinate international support for “mobile courts” (or in situ hearings). They aim to increase capacity and encourage better performance, by bringing some external scrutiny over the work of Congolese justice officials.[59]

A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to regulate the functioning of the UN Prosecution Support Cells was concluded between the Congolese government and MONUSCO in December 2011. Eight UN Prosecution Support Cells have been established in total, in Beni, Bukavu, Bunia, Goma, Kalemie, Kindu, Kisangani, and Lubumbashi.[60] The UN Prosecution Support Cells have made the tacit decision to only get involved if asked by national judicial authorities in connection with a specific case.[61] Over the past three years, the cells had received over 40 requests for support from the Congolese justice system covering several hundred suspects.[62]

Because one of the key challenges in the fight against impunity in Congo is the insufficient quality of investigations and prosecutions, the UN Prosecution Support Cells represent a targeted response with the potential to make an important difference. Given that a number of other international partners are also involved in logistical support to the justice system and the organization of mobile courts, technical assistance to investigations and prosecutions is the most novel part of their mandate and should be the focus of their action.

Parties and observers in the Minova case, including military justice officials, voiced a number of concerns regarding the UN Prosecution Support Cells’ assistance. The UN Prosecution Support Cell experts who were deployed in the region at the time did not actually have prior experience related to prosecuting grave international crimes or international criminal law.[63] This not only limited their ability to provide quality training or specialized technical advice on how to approach complex, mass crimes, but also undermined their legitimacy with Congolese justice officials.

UN Prosecution Support Cell experts were also said to be too passive regarding the implementation of their mandate. They were not involved directly in investigations, invoking respect for national sovereignty.[64] Instead, when asked, they provided very basic feedback and some technical advice regarding investigative techniques, such as writing up victims’ and witnesses’ statements taken in Minova and drafting a letter rogatory.[65]

As illustrated above, the military investigators and prosecutors would have needed sophisticated advice to prepare an investigation plan and prosecutorial strategy to enable them to establish criminal responsibility for a mass crimes scene, involving over a thousand victims and numerous perpetrators. UN Prosecution Support Cell experts interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that it was not their role to give advice on investigative strategy or to press for specific targets to be prosecuted on the basis of the evidence collected in the Minova case. Other UN officials disagreed with this limited approach and said the Prosecution Support Cells could and should do more.[66]

In conclusion, it seems that important weaknesses in the Minova investigation can be explained by a lack of expertise and diligence on the part of military investigators and prosecutors. Intense pressure from the international community and authorities in Kinshasa seems to have been a factor in the Minova case going to trial in a rushed manner in November 2013.[67] Yet it is not clear that more time would have necessarily resulted in a significantly better investigative file. No investigative steps were taken between the interviews with commanders in April 2013 and the issuing of arrest warrants in early November 2013, squandering over half a year of possible work. In addition, the military investigators and prosecutors in the Minova case with whom Human Rights Watch spoke for this report stated that, from their point of view, the investigation was complete when the file was sent to trial.[68]

Capacity-building for military police and prosecutors in the field of international crimes and sexual violence is important to help increase the number of officials with specialized expertise. International crimes are often more challenging to investigate and successfully prosecute than “ordinary” crimes, due to the complexity of the law, the scale of the crimes, and the large number of players involved.[69]

At the same time, a lack of genuine will or interference from the judicial hierarchy or political and military authorities can adversely impact the quality of investigations, no matter the amount of technical training provided to judicial staff. Several observers pointed out that, while certainly a gap, it is not clear that improved expertise and better investigations would have made a fundamental difference in the outcome of the Minova case.[70]

III. Fair Trial Issues

Justice is realized in the criminal justice system when the rights of the accused under international law are fully respected, including receiving a fair and public trial before a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal.[71]

More attention was paid to respecting the rights of the accused in the Minova case than in many other war crimes trials in Congo.[72] For example, all defendants had legal representation throughout the trial hearings and the judges took the time to hear all parties and to allow questioning of witnesses by defense lawyers. Most defendants were also physically present during their entire trial, with the exception of four officers who were called back to the front-lines.[73] Motions presented by the defense were given due consideration and Operational Military Court judges granted some of their requests, including a motion to delay the start of the trial to allow more time for the defense to prepare.[74]

Yet, despite these positive elements, there were serious shortcomings regarding the fairness of the proceedings.

Lack of Clear Evidence against Many Convicted Soldiers

Trial monitors and parties involved in the proceedings told Human Rights Watch that the evidence that the prosecution presented in the Minova case was both vague and weak against most defendants.[75]

The indictments against 18 rank-and-file soldiers were fully identical and did not specify any date, location, victim, or conduct with regards to rape and pillage accusations against them. During the hearings, judges questioned most soldiers only about their alleged absence from camp during the roll calls.[76] The commander of the 391st Battalion, Capt. Patrick Kangwanda Swana, kept a log book with written records of the roll calls, including during the time in Minova, but other commanders did not.[77] The only evidence about unauthorized absence against many soldiers was therefore their commanders’ recollection and word. Most soldiers denied having missed the roll calls. Being absent when ordered to stay in the camp was a violation of military orders (also a criminal charge against the soldiers in the case), but should be insufficient to prove involvement in the other crimes, namely pillage and rape. Examples of statements made by the soldiers during the hearings include:

Judge to defendant Kaserera-Bolali Roger: “Were you present at the roll call?”

Kaserera-Bolali: “Yes.”

Judge: “Why is your name on the list [of those absent], then?”

Kaserera-Bolali: “It was what came out of their mouth, they said they were going to sacrifice the soldiers.”[78]

Judge to defendant Mogisha: “You were absent for four days, why?”

Mogisha: “[My commander] said that I am undisciplined, that I need to be sacrificed.”

Later, after Mogisha’s commander says that he was arrested with a new jacket in his possession:

Judge to Mogisha: “Did you hear what your commander said?”

Mogisha: “It is not true. Since then, [my commanders] keep creating troubles for me. They say we are bad soldiers. They even asked me for money!”[79]

The CMO judges acquitted all but two soldiers of rape, citing briefly in the judgment a lack of evidence.[80] At the same time, the judges found all rank-and-file soldiers guilty of the war crime of pillage, in addition to violating orders, and sentenced them to heavy prison sentences.[81] A non-governmental organization staff member who followed the trial closely told Human Rights Watch:

It was a bit of a sacrifice, this trial. Soldiers not staying at the camp is a common phenomenon in Congo; absence at roll calls does not prove anything. And this young captain [Captain Kangwanda], he now has a lot of problems for having given the names of the soldiers, even if he was not convinced himself of their guilt in the first place.[82]

A military judicial official involved in the trial said:

The soldiers were not happy at all. They were sacrificed. They were convicted just because of their absence that day. The court found them guilty of pillage without any evidence, maybe to please the international community.[83]

No Right to Appeal

Article 87 of the Congolese Military Judicial Code states that the judgments of military operational courts cannot be appealed.[84] While all parties in the trial before the CMO are affected by this provision, including the prosecution and victim participants, it has particularly serious consequences for defendants who face stiff sentences—including the death penalty—in trials for serious international crimes. The provision is contrary to the fundamental right to have one’s judgment and sentence reviewed by a higher tribunal, which is enshrined in the Congolese Constitution and international law.[85]

At the start of the trial on December 4, 2013, lawyers from the American Bar Association (ABA) who represented some of the victims filed a preliminary motion arguing that the absence of the right to appeal was unconstitutional.[86] They asked that the CMO refer the matter to the Supreme Court of Justice to resolve the issue. The following day the CMO judges rejected the motion on the grounds that it had been poorly argued in that it did not cite the correct law at issue, namely the presidential decree of January 2008 creating the CMO.[87] The victims’ lawyers still later tried to appeal the Minova judgment after the verdict before the High Military Court in Kinshasa, arguing that there were errors in the judgment. The High Military Court had not responded to the request at time of writing.

Only victims’ lawyers tried to act on this issue in the Minova trial. The defendants’ lawyers did not try to assert their clients’ right to appeal either at the beginning or at the end of the trial, even though several were sentenced to heavy prison sentences despite a lack of evidence, as discussed above. This may be an indication of the poor legal representation available for some of the defendants.

Weak Legal Assistance for Rank-and-File Soldiers

The Minova case was marked by a stark variation in the quality of defense available to the accused. The officers who were able to choose and pay their legal representative received a competent and strong defense on legal and factual issues.[88] The pro deo (pro bono) lawyers who were assigned to soldiers for no payment had no expertise in international crimes cases and provided a considerably less vigorous and effective defense.[89]

None of the defendants in the Minova case had access to a lawyer during investigations, including when they were formally interrogated. This was contrary to article 19 of the Congolese Constitution, which states that an accused person should have access to legal assistance at all stages of the criminal proceedings.[90] The defense lawyers noted that this created difficulties and contradictions later during the trial.[91]

All lawyers were nominated on the day of the opening of the trial, or later.[92] Even if the CMO judges eventually agreed to a 15-day adjournment to enable lawyers to prepare, this was still a brief time frame to study a voluminous and complicated file and to consult with clients. The designated lawyers from the Goma Bar Association had little or no experience with grave international crimes and most had never received training on international criminal law.[93]

In addition, pro deo lawyers did not receive any payment. The UN Development Program (UNDP) covered transportation in Goma, as well as transportation, accommodation, and meals for the defense lawyers who went to attend the in situ hearings in Minova, but no government compensation or other support was granted.[94] This limited financial support created real difficulties.

Access to the case file was a challenge. Only one paper copy of the Minova file exists and it was kept at the registry of the CMO in Goma. Consulting the file at the registry is without cost but can only be done during specific hours and is not possible during hearings.[95] It is therefore much more practical for the lawyers to have a copy of the file to study outside the registry. But, under Congolese judicial rules, heavy fees have to be paid to make copies of the case files.[96] Even if the CMO judges ordered that these fees should not be paid by pro deo lawyers in the Minova case, they still could not cover the cost of making the actual copies, in the absence of financial or technical support.

Also, the length of the trial made the lack of compensation even more problematic. This led to inconsistent attendance at trial by pro deo lawyers.[97] Some tried to come to most hearings at their own expense, while others did not come at all.[98] A group of lawyers organized to attend the hearings in rotation. This was insufficient, however, because they did not necessarily inform each other of what had happened in court. Due to their inconsistent attendance, the lawyers sometimes raised issues that had already been discussed or failed to follow up on important points.

IV. Determination of the Accused and Command Responsibility

Military prosecutors have broad discretionary power, based on evidence found during investigations, to decide which suspects should be indicted and brought to trial.

Seven soldiers caught in the act (in flagrante delicto) and arrested in and around Minova in November 2012 were among the accused brought to trial. But due to the circumstances at the time, including the large number of soldiers present in the area, it was extremely difficult for the prosecution to identify more direct perpetrators of the numerous rapes and acts of pillage. Under international law, however, it is not only those who commit the crimes who bear criminal responsibility, but, in certain circumstances, their military and civilian superiors.

From the onset, it was clear to most participants and observers in the Minova case that justice would hinge on the ability and willingness of the military justice system to investigate and establish the role played by commanders.[99] An NGO observer close to the investigation and trial said: “It was a situation where abuses were committed en masse. It was difficult for the victims to precisely identify their attackers. It was clear that one needed to look into the responsibility of the commanders.”[100]

A military justice official involved in the investigation said: “Given that none of the victims could recognize the direct perpetrators, we had to look into the responsibility of their commanders, who should have taken precautions or other measures.”[101]

Yet, the vast majority of interviewees for this report said that they believed the “real suspects” were not in the dock in the Minova trial.[102] In this section, we review how the military justice system handled the responsibility of commanders.

Command Responsibility Theory

“Command responsibility” as a mode of liability does not exist under Congolese law and is often misunderstood. In the Minova case, like in previous cases before military courts, the Congolese military prosecutors and judges used article 28 of the Rome Statute, which defines this theory.[103]

It is a widely accepted principle of criminal law that commanders who incite, order, facilitate, take part, or are complicit in the crimes should be investigated. All these actions imply criminal intent (mens rea) on the part of the commanders and direct or indirect involvement in the crimes.

But international law goes beyond this and foresees that commanders can also be held criminally responsible for the actions of their subordinates if they failed to prevent, stop, or punish grave violations of international humanitarian law, provided certain requirements are met. Under the “command responsibility” theory, commanders therefore bear responsibility because of their inaction in the face of grave international crimes.

Command responsibility, which was first applied in post-World War II prosecutions, is codified in article 86 of the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, as well as the statutes of several international and hybrid criminal tribunals, and many national criminal codes and military manuals.[104] It is an important legal theory to hold accountable military and civilian superiors of troops responsible for atrocities, given that these persons are often not directly involved in the crimes or even present when they are committed.

The development of this mode of liability comes from the recognition that grave violations of the laws of war are often committed by low-level military personnel because their superiors fail to prevent or punish these crimes. A passive attitude on the part of commanders in the face of grave abuses can encourage further crimes. It would be wrong for commanders standing by as serious crimes are committed to escape criminal responsibility just because they do not carry the weapon or order the offense.

Under command responsibility, commanders have an active duty to ensure that their subordinates respect the laws of war and to appropriately punish those responsible for violating them. According to international law and jurisprudence, four elements must be met for a military or civilian superior to hold individual criminal responsibility for crimes perpetrated by his subordinates: 1) the accused was the superior, de jure or de facto, of persons who committed a crime; 2) the accused had effective control over these persons; 3) the accused knew or should have known that their subordinates were committing or about to commit a crime; and 4) the accused failed to prevent or stop the crimes, or, if the crimes had already been committed, punish those responsible.[105]

Command Responsibility in the Minova Case

No information emerged during the trial suggesting that soldiers were ordered or encouraged to rape and pillage in Minova and surrounding villages. The question therefore is whether commanders responsible for the troops in Minova had control over them, knew or should have known about the crimes being committed, and did what was necessary to prevent, stop or, if the crimes had taken place, punish the soldiers responsible.

A total of 14 officers, holding ranks ranging from captain to lieutenant-colonel, were indicted. Thirteen of these 14 officers were charged for war crimes committed by troops under their command as a matter of command responsibility. Twelve belonged to the 41st and 391st Battalions of the 8th Military Region. The two senior commanders and four low-level company commanders from each battalion were indicted. An officer from a military police battalion was also charged under the command responsibility theory.

In the judgment, the Operational Military Court judges went over the “command responsibility” requirements listed above, citing international jurisprudence, and decided to acquit all indicted commanders. The military police battalion officer was acquitted because no evidence was presented that soldiers under his command were involved in the crimes. The judgment concerning the other commanders is discussed below.

Two Dismissed Battalion Commanders

The original commanders of the 391st and 41st Commando Battalions, Colonels Nzale and Ntore, were among those indicted in the case under command responsibility. According to testimonies heard at trial and the judgment, they had been dismissed from their command positions by Gen. Gabriel Amisi, the commander of land forces at the time, on November 19, 2012, before he ordered the retreat towards Minova. (They were allegedly dismissed because of their poor performance in military operations during the fall of Goma.[106]) Nzale was taken prisoner by M23 fighters on November 20, while Ntore went to Bukavu for medical treatment.[107] They never went to the Minova area and were suspended of all military duties at the time of the crimes.

These two officers were nonetheless indicted for the war crimes of pillage and rape committed in Minova. In addition, the prosecution introduced an additional indictment against them for “demoralizing the troops.”[108] According to trial observers and lawyers who attended the hearing, General Mukunto threatened the two officers in the courtroom.[109] In the official records of the hearing, as the case on war crimes charges was drawing to an end, he is quoted as saying:

Regarding the court’s decision to acquit Lieutenant Colonel Nzale under the case RP 009/2013 [for demoralizing the troops], the prosecution promises him that he is a traitor and a traitor can betray again, his place is not in the FARDC [Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo]! This applies to Lieutenant Colonel Wasinga Ntore too.[110]

The CMO judges demanded that General Mukunto stop the threats. In the judgment, the judges found that Colonels Nzale and Ntore did not have effective control over the troops that committed the crimes in Minova because “they were not in function anymore, did not have the capacity to give orders, and exert control over their implementation anymore or to punish the crimes. Control had been handed over to those replacing them since their dismissal in Mubambiro on November 19, 2012.”[111] The court eventually acquitted the two commanders of all charges.

The prosecution of these commanders was interpreted by many as an attempt to make them scapegoats for the Minova crimes because of their poor performance during military operations. A defense lawyer told Human Rights Watch:

The government really wanted these officers to be convicted. That is why Mukunto came from Kinshasa, so that they could say that these two were responsible for the crimes in Minova. He threatened them during the hearing—it was clear that he came to show what needed to be decided.[112]

A military justice official involved in the Minova investigation said: “Officers who had never arrived in Minova were prosecuted. That did not make any sense. These two were innocent and others should have been indicted.”[113]

Acquittal of Other Commanders

For the remaining officers, the judges found that they were indeed in charge, had effective control over the troops in Minova, and knew that crimes were being perpetrated.

The judges however decided that the criminal responsibility of these commanders for the crimes in Minova could not be established because they “did not fail to punish the crimes or to refer the suspects to the judicial authorities.” They added: “As a matter of fact, it is thanks to these commanders that the suspects have been identified and brought to this court.”[114]

But there are problems with this reasoning. First, while it is true that the battalion commanders gave the judicial authorities the names of soldiers who were later prosecuted, they only did so in April 2013, upon General Mukunto’s request. A handful of soldiers caught drunk or in possession of looted goods were referred to the judicial authorities at the time of the Minova events but most soldiers arrested in Minova were later released and reintegrated. In addition, as established during the questioning of commanders at trial, no official military reports were filed on the crimes, suggesting that these commanders did not really intend to act on the crimes in Minova.[115]

Second, the decision does not discuss other elements of command responsibility, notably whether the commanders took any steps to prevent or stop the crimes. There is no discussion in the judgment of measures that the commanders could have taken as they led their troops towards Minova, such as instructing their subordinates about the need to protect civilians in accordance with the laws of war. According to testimony at trial, several commanders were at times located just a couple hundred meters from where the crimes were being committed.[116] At trial, the judges repeatedly asked the commanders why they did nothing other than wait around and do roll calls when they heard the gunshots.[117] In the judgment, however, the court finds that the commanders could not leave camp while the crimes were ongoing, as this could have worsened the situation by leaving the soldiers without supervision.

International jurisprudence recognizes that the determination of whether commanders took “all necessary and reasonable measures” requires a case-by-case analysis of the facts of the case and of what the superiors were in a position to do in the given circumstances.[118] International tribunals have determined that commanders must take measures that are “specific and closely linked to the acts they are intended to prevent.”[119] As such, it is not clear that routine measures such as roll calls would be sufficient, at least concerning the superior officers, such as battalion commanders.[120]

The CMO bench, in accordance with the Congolese Military Judicial Code, was composed of two professional military judges and three military officers from the 8th Military Region, with no legal training, acting as associate judges. These associate judges are chosen randomly from a list prepared by the military command.[121] Judgments are decided by majority, following a secret vote. One military judge indicated that in cases involving grave international crimes and complicated legal theories such as command responsibility, benches should always be composed of at least a majority of professional military magistrates.[122]

Other Officers Not Indicted

Evidence presented at trial, including testimonies and citations from investigative interview notes, established that a number of officers above those indicted in the case were also present in Minova during the crimes. These high-ranking officers were questioned by the General Military Prosecution Office in the course of the investigations, but they were neither called as witnesses during the trial nor indicted.

A military justice official involved in the case told Human Rights Watch:

Several commanders were interviewed but not indicted. Why this commander and not that one? It is important to realize that there were de jure and de facto commanders in Minova. Nobody tried to establish who was really in charge there.[123]

For example, senior officers were nominated “coordinators” and asked to take responsibility for some of the battalions in Minova for the period of the reorganization.[124] The indicted commanders said at trial that they regularly reported to and took their orders from these officers while in Minova. Although they were not the regular hierarchical superiors of the battalion commanders, these officers were de facto in charge of some of the troops at the time.[125] Under the command responsibility theory, the role of a de facto commander can also be examined.

In addition, several testimonies and interview statements in the case asserted that the entire high command of North Kivu’s 8th Military Region was in Minova at the time of the crimes, including Gen. Jean-Lucien Bahuma, the commander of the 8th Military Region, and several colonels belonging to the region’s headquarters battalion.[126] Some high-ranking officers from South Kivu’s 10th Military Region were also present.[127]

According to testimonies and witness statements, many of these senior officers took part in a military strategy meeting on November 22 at the Lwanga Institute, near the Catholic parish in Minova. November 22 is one of the dates most cited by victims at the Minova trial for when the crimes took place.

The Minova judgment states that commanders of the 8th Military Region admitted during the interviews with the military prosecutors that pillage and rape happened on a mass scale in Minova. General Bahuma is reported to have said that “there was a problem of control over the troops, which allowed soldiers to leave their units and go into Minova town where they committed the crimes that were later denounced by the civilian population.”[128]

There was no testimony at trial about what the high-level command did to prevent or stop the crimes happening at the time. A lawyer with access to the investigation file and notes of the interrogations of these commanders told Human Rights Watch: “The questioning [of these top commanders] was weak. They were not asked where they were, what they did as the crimes were being committed and after.”[129] There was also no information put forward about steps these high-level commanders may have taken to ensure justice was served for the crimes in Minova.

At trial, several indicted commanders said that the high command of the military region was present and in charge in Minova and that it would therefore have been difficult for them, as low-level commanders, to take the initiative to stop the crimes. A defense lawyer said in court:

You cannot limit yourself to the commanders lower down in the chain of command. All these people received orders; you need to check what was done by the top commanders in Minova.[130]

The presiding judge of the CMO replied:

This court is seized of the indictments it has received; you can’t ask us to make anybody else come. It is for the prosecution to decide whom to prosecute.[131]

Human Rights Watch asked several military justice officials involved in the Minova case why these other commanders were not indicted. One military justice official involved in the investigation said:

We could have gone all the way up to General Bahuma but the decision was made to stop at low-level field commanders. I don’t have an explanation for that. I was not the one who decided who should be indicted.[132]

A military investigator involved in the investigation said: