It should be no surprise that the first year of the Trump presidency has been brutal for refugees. Not only are resettlement numbers down to the lowest levels recorded in the nearly 40-year history of the program, but the trends by nationality raise disturbing questions in light of the president’s hateful and bigoted rhetoric about refugees and immigrants.

Reflecting his contempt for a program he has compared to a “great Trojan horse,” the State Department’s refugee bureau has been leaderless since Donald Trump became president. But that could change with the May 24 nomination of Ronald Mortensen, to serve as assistant secretary of State for the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration. Mortensen is a retired foreign service officer with humanitarian-assistance experience, but he is also an outspoken critic of illegal immigration and a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates for restrictions on newcomers to the U.S.

Mortensen’s nomination has to be confirmed by the members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The committee should take a close look at his writings. He has accused Sen. John McCain of “dogged support for illegal aliens [that] has left the United States vulnerable to terrorists.” In an op-ed for the Hill, he characterized the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program as rewarding Dreamers “for destroying the futures of innocent American children.” The senators should also ask Mortensen what he thinks about worrisome trends already in effect in the refugee program.

At the halfway point of this fiscal year, the United States had admitted only 10,548 refugees, a 74% drop compared with the same period in 2017. This at a time when Middle Eastern nations are struggling to maintain asylum for 5.6 million Syrian refugees, when more than 700,000 displaced Rohingya have poured from Burma into Bangladesh, and when most of the world’s 20 million refugees are stuck in protracted situations with little prospect of returning home anytime soon.

The Trump administration has slowed down refugee admissions by throwing sand into the gears of resettlement processing. This has included “extreme vetting” and the redeployment of the Refugee Corps officers, who usually interview potential resettlement candidates in overseas camps, to the stepped-up efforts at the U.S. border to interview people making asylum claims.

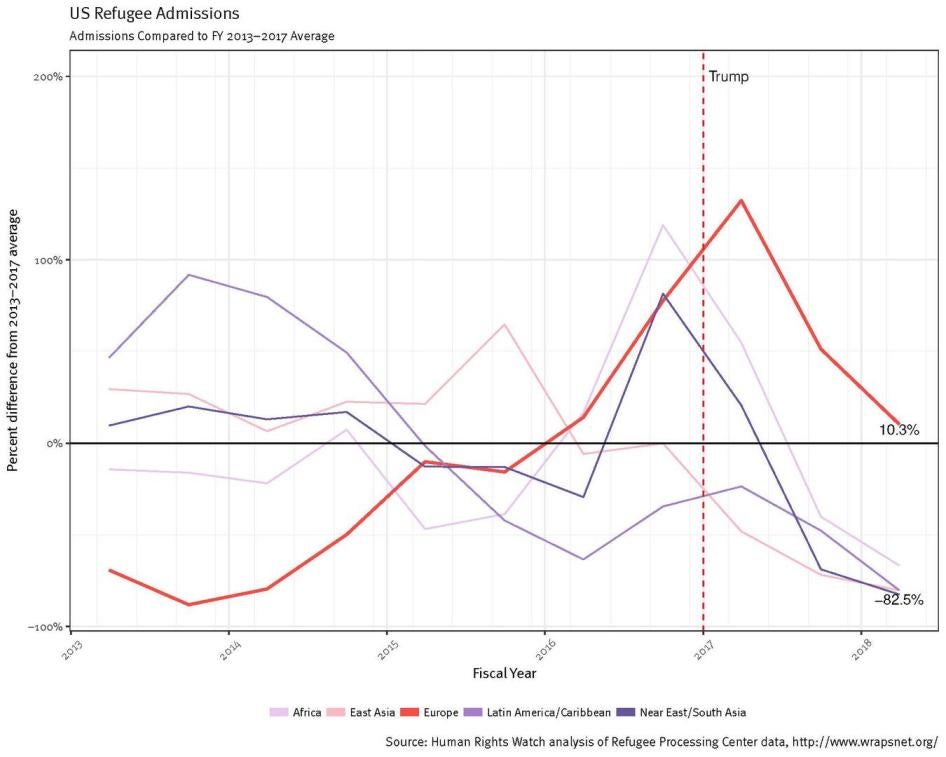

The slowdown in resettlement and the falling overall numbers of refugee admissions tell only part of the story.

We examined the latest fiscal year 2018 refugee data against averages from the previous five years and found that the plunge in admissions has largely spared a handful of white-majority European countries. The U.S. is currently admitting 110% of the European admissions it had typically resettled while admitting only 22% of the usual numbers from the rest of the world. Admissions are down from the five-year average by 67% from African countries, and about 80% from Middle Eastern/South Asian countries, East Asian countries, and Latin America/Caribbean countries.

Admissions from countries covered by the president’s travel ban have virtually ceased — refugees from Iran are at 2.2% of the five-year averages; from Syria, at 1.8%; from Somalia, 4.5%.

Admissions from Ukraine are up 109%, and Russia, 134%. This pattern is also reflected in regional targets. Halfway through the fiscal year, the European regional ceiling is already 87% filled, overwhelmingly by Ukrainian Christians, but the Middle East/South Asia ceiling is only 16% filled. And 72% of the refugees admitted from that region so far this year are non-Muslims, down from 54% in the previous five years.

“The process works like the assembly line in a factory,” Barbara Strack, who retired in January as chief of the Refugee Affairs Division at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, told the New York Times. “This fiscal year, the administration essentially ‘broke’ the assembly line in multiple places at the same time.”

President Trump has scapegoated refugees, called for a total ban on the entry of Muslims, and expressed an immigration preference for people from places like Norway. It’s now up to the Senate to discover whether Mortensen will bend a truncated U.S. refugee resettlement program further toward the president’s prejudices or consider restoring a system that has provided hope and rescue for some of the world’s most persecuted and vulnerable people.