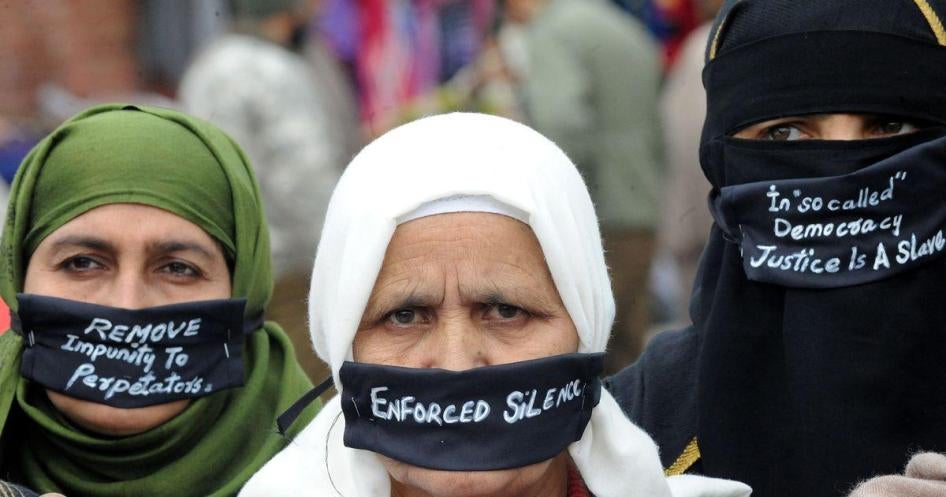

Protests broke out in Jammu and Kashmir after soldiers shot and killed six persons in Shopian district on March 5. An Army spokesman claimed all six were involved in terrorism either as militants or “overground workers”, the government’s term for civilians who provide ideological or material support to armed groups. The spokesman said they had failed to stop at a checkpoint and had opened fire at the soldiers, who had acted in self-defence. Protestors say four of the men were not militants but victims of a staged armed encounter or indiscriminate shooting. They are demanding an impartial investigation.

These allegations are not surprising. Security forces in India have over the years been accused of engaging in extrajudicial killings. While soldiers deployed in counterinsurgency are shielded from criminal prosecution by the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, police and federal forces also have effective legal immunity from prosecution. Serious concerns about police killings during security operations date back to Punjab through the mid-1990s to the Maoist insurgency today. In a 2016 report on deaths in police custody in India, Human Rights Watch not only documented violations of arrest procedures by the police leading to abuses, but found that investigating officers will shield their colleagues rather than bring those responsible for abuses to justice.

The Bharatiya Janata Party-led government, however, seems to be taking this impunity one step further. Criticism of human rights abuses is deemed unpatriotic by the party’s ultranationalist supporters. Perpetrators are frequently protected, such as the officer who strapped a civilian atop a military vehicle as a human shield against stone-throwing protestors in Kashmir in April. Instead of prosecuting him, the government praised the officer’s actions and honoured him with a commendation. Ignoring complaints from Kashmiris, the attorney general at the time said the “Army should be applauded”. In February, some BJP leaders joined the Hindu Ekta Manch in a demonstration in support of a Hindu police officer accused of raping and killing an eight-year-old Muslim child in Jammu.

Controversy continues to surround the case of BJP president Amit Shah, who was arrested in 2010 for his alleged role in an extrajudicial killing by the police in Gujarat. In November last year, the National Human Rights Commission issued a notice to the BJP chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, Adityanath, after he said “criminals will be jailed or killed in encounters”. The commission warned that such a statement was tantamount to giving security authorities “a free hand to deal with the criminals at their will and, possibly, it may result into abuse of power by the public servants”.

While all killings by security forces are supposed to be investigated, as the Supreme Court reminded the government in July 2016, there are serious concerns over the possibility of independent inquiries when there is open support for alleged perpetrators from political leaders. In Uttar Pradesh, a police crackdown has led to the killing of 39 alleged criminals since March 2017.

Reforms needed

Numerous international experts, including the United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, have called upon India to address unlawful killings and excessive use of force by security forces. Yet, instead of engaging in security sector reform and training law enforcement officials to act in a rights-respecting manner, the authorities in India are often selective in ensuring justice and accountability.

The presumption of innocence is not a vague concept. It exists to protect the weak and vulnerable. Instead of taking short cuts and unlawfully killing suspects, Indian authorities should instruct the commanders of police and soldiers to go back to basics – find evidence and prosecute crimes. When it is left to the security forces to be both jury and executioner, the entire criminal justice system breaks down.

Deep reforms are necessary. One place to start is by following the recommendations of numerous government commissions to repeal the Armed Forces Special Powers Act and replace it with a law that upholds human rights. The government should also strictly enforce laws and guidelines set out by the Supreme Court and the National Human Rights Commission, clearly and unequivocally signal through public messaging and prompt accountability that there will be no tolerance for unlawful killings by security forces.