"Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime"

Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India's ChhattisgarhState

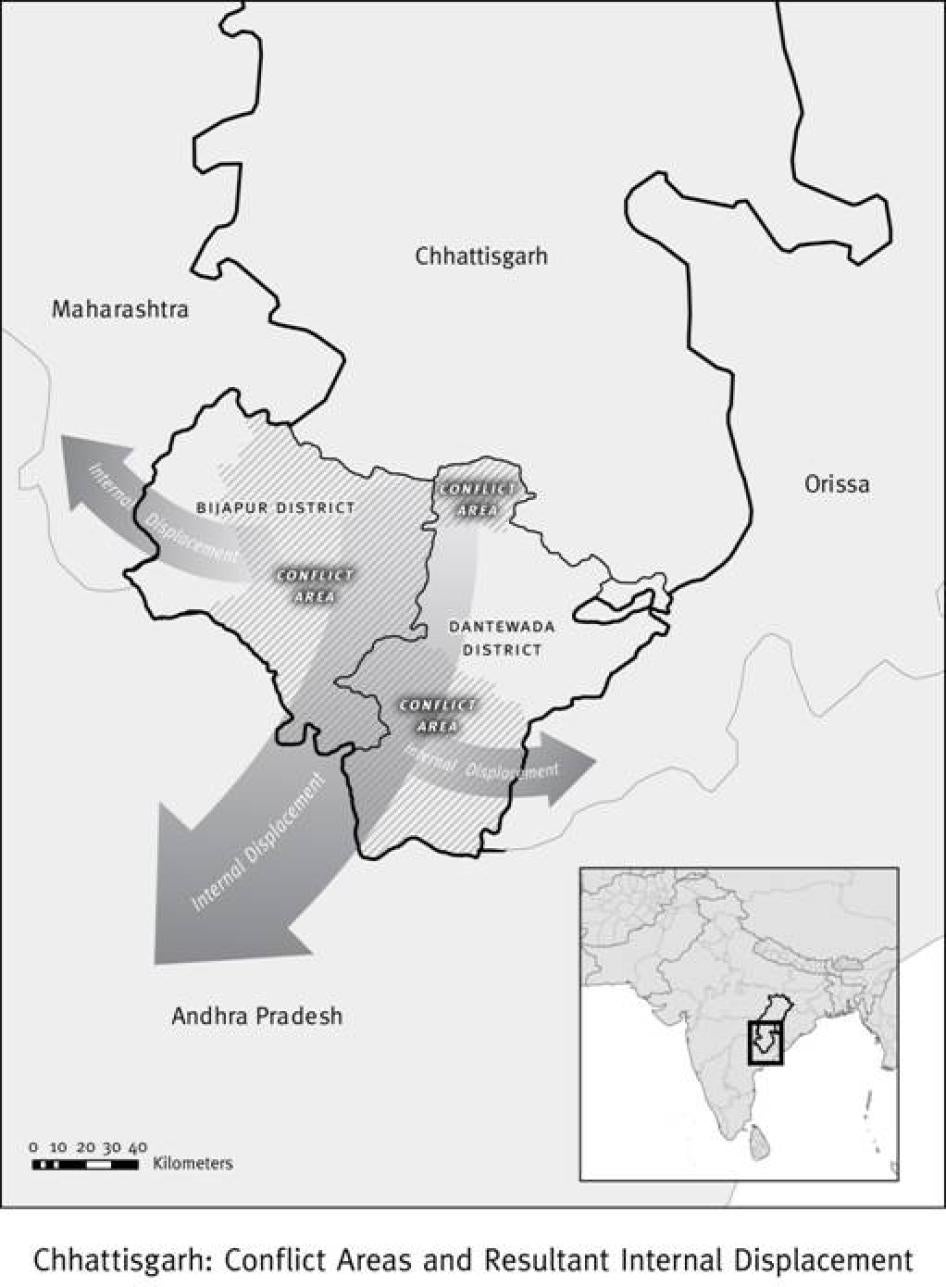

Maps

© 2008 John Emerson

© 2008 John Emerson

Glossary/ Abbreviations

Abhiyan |

Campaign |

Adivasi |

Literally meaning "original habitant," a term used to refer to indigenous tribal communities in India |

Anganwadi |

Government-run early childhood care and education center under the Integrated Child Development Services Scheme |

Ashram school |

Government-run residential school in rural areas |

Bal sangam |

Village-level Naxalite children's association |

Block |

Administrative division. Several blocks make a district |

CAF |

Chhattisgarh Armed Force, under the control of the Chhattisgarh state government |

CNM |

Chaitanya Natya Manch,a street theater troupe organized and managed by Naxalites |

CPI (Maoist) |

Communist Party of India (Maoist), a prominent Naxalite political party |

CRPF |

Central Reserve Police Force, paramilitary police under the control of the Indian central government |

Dalam |

Armed squad of Naxalites |

Dalit |

Literally meaning "broken" people, a term for so-called "untouchables" |

DGP |

Director general of police |

District |

Administrative division. Many districts make a state |

District collector |

Highest district-level administrative officer |

Director general of police |

Highest police official in the state |

|

Gram Panchayat/ Panchayat |

Literally meaning "assembly of five," a term used to refer to the village-level councils of elected government representatives |

ICCPR |

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

ICESCR |

International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights |

IED |

Improvised explosive device |

IRB |

Indian Reserve Battalion, paramilitary police under the control of the Indian central government |

ITDA |

Integrated Tribal Development Agency |

Jan adalats |

"People's courts" organized by Naxalites |

Jan militia |

Armed informers who travel with dalams |

MHA |

Ministry of Home Affairs |

NCPCR |

National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights |

NHRC |

National Human Rights Commission |

Patel |

Village headman |

PLGA |

People's Liberation Guerrilla Army, standing army of CPI (Maoist) party |

Sangam |

Village-level Naxalite association |

Sarpanch |

Village official-head of the gram panchayat |

SHRC |

State Human Rights Commission |

SP |

Superintendent of Police |

SPOs |

Special police officers, auxiliary police force |

Superintendent of police (SP) |

Highest district-level police officer |

Tribe/tribal |

Term used to refer to indigenous people in India |

I. Summary

We often wonder what sins we committed to be born at this time. Our lives are impossible. Naxalites come and threaten us. They demand food and ask us to help them with information about police movements. Then the police come. They beat us and ask us for information. We are caught between these people. There is no way out.

- A resident of Errabore, a government-run camp, January 2008

In Chhattisgarh state in central India, a dramatic escalation of a little-known conflict since June 2005 has destroyed hundreds of villages and uprooted tens of thousands of people from their homes. Caught in a deadly tug-of-war between an armed Maoist movement on one side, and government security forces and a vigilante group called Salwa Judum on the other, civilians have suffered a host of human rights abuses, including killings, torture, and forced displacement.

The armed movement by Maoist groups often called Naxalites spans four decades and 13 states in India. They purport to defend the rights of the poor, especially the landless, dalits (so-called "untouchables"), and tribal communities. Their repeated armed attacks across a growing geographical area led Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2006 to describe the Naxalite movement as the "single biggest internal security challenge ever faced" by India.

Naxalites have maintained a strong presence in southern parts of Chhattisgarh since the 1980s. Although many indigenous tribal communities living in these areas support Naxalite interventions against economic exploitation, an escalating pattern of Naxalite abuses, including extortion of money and food, coerced recruitment of civilians, and killings of perceived police informants or "traitors," has gradually alienated many villagers.

In June 2005 popular protests against Naxalites in Bijapur district in southern Chhattisgarh sparked the creation of Salwa Judum, a state-supported vigilante group aimed at eliminating Naxalites. Salwa Judum's activities quickly spread to hundreds of villages in Bijapur and Dantewada districts in southern Chhattisgarh. With the active support of government security forces, Salwa Judum members conducted violent raids on hundreds of villages suspected of being pro-Naxalite, forcibly recruited civilians for its vigilante activities, and relocated tens of thousands of people to government-run Salwa Judum camps. They attacked villagers who refused to participate in Salwa Judum or left the camps.

Naxalites have retaliated against this aggressive government-supported campaign by attacking residents of Salwa Judum camps, and abducting and executing individuals they identified as Salwa Judum leaders or supporters, police informers, or camp residents appointed as auxiliary police.

Neither the government nor Naxalites leave any room for civilian neutrality. Seeking protection from one side leaves area inhabitants at risk of attack by the other. Local journalists and activists who have investigated or reported abuses by Salwa Judum and government security forces have been harassed and described as "Naxalite sympathizers" by the Chhattisgarh state government, and live in fear of arbitrary arrest under the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act, 2005.

Even though some officials acknowledge that Salwa Judum's activities have exacerbated the violence, resulting in loss of civilian life and property, the Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments have failed to prevent or stop these abuses or hold those responsible accountable. In April 2008 the Supreme Court of India ordered the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to investigate complaints of abuse.

While there is hope that the NHRC will conduct a thorough investigation of abuses by both sides, many analysts believe that unless the Indian central and state governments acknowledge and remedy their failure to uphold the rights of tribal communities, the Naxalite movement will continue to grow. The governments must immediately address the human rights and humanitarian catastrophe that has resulted from their policies in Chhattisgarh and hold all those responsible accountable.

Government and Salwa Judum abuses

The Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments claim that Salwa Judum is a "voluntary and peaceful initiative by local people against Naxalites." Human Rights Watch, however, found overwhelming evidence of direct state involvement in Salwa Judum and the group's involvement in numerous violent abuses.

Over a period of approximately two-and-a-half years, between June 2005 and the monsoon season of 2007 (June to September), government security forces joined Salwa Judum members on village raids, which were designed to identify suspected Naxalite sympathizers and evacuate residents from villages believed to be providing support to Naxalites. They raided hundreds of villages in Bijapur and Dantewada districts, engaging in threats, beatings, arbitrary arrests and detention, killings, pillage, and burning of villages to force residents into supporting Salwa Judum. They forcibly relocated thousands of villagers to government-run makeshift Salwa Judum camps near police stations or paramilitary police camps along the highways. They also coerced camp residents, including children, to join in Salwa Judum's activities, beating and imposing penalties on those who refused.

Although Salwa Judum's raids were most frequent between June 2005 and mid-2007, they continue to carry out violent attacks in reprisal against former camp residents who have returned to their villages. There have also been reports of government security forces executing persons suspected of being Naxalites and labeling the executions "encounter killings," falsely implying that the deaths occurred during armed skirmishes.

Police arbitrarily detain individuals as suspected Naxalites, interrogate them, and in some cases, subject them to torture. Chhattisgarh police have recruited camp residents including children as special police officers (SPOs), an auxiliary police force, and deploy them with other paramilitary police on joint anti-Naxalite combing operations. This has exposed underage SPOs to life-threatening dangers, including armed attacks by Naxalites, explosions due to landmines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and Naxalite reprisal killings.

Since 2006 local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have reported the recruitment of underage SPOs by the Chhattisgarh police. The Chhattisgarh state government maintains that it has now removed all children from its ranks. Some officials claim that the recruitment occurred because many villagers did not have proper age records. However, Human Rights Watch found that there continues to be no procedure or scheme for systematically identifying, demobilizing, and reintegrating underage SPOs. The lives of underage SPOs who have not been identified and reintegrated remain at risk.

These ongoing human rights abuses have resulted in a massive internal displacement crisis that is yet to be addressed by the Indian central or concerned state governments. By December 2007 around 49,000 villagers had been relocated to at least 24 camps in Bijapur and Dantewada districts, while many others had fled to safer parts of Chhattisgarh. An estimated 65,000 villagers had fled to adjoining states of Maharashtra, Orissa, and Andhra Pradesh to escape the conflict. Roughly 30,000-50,000 have settled in Andhra Pradesh.

Three years after the forcible relocation of local populations into camps and the exodus from Chhattisgarh to neighboring Andhra Pradesh began, neither the Indian central nor the Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh state governments have developed a comprehensive policy to provide these displaced persons with protection and assistance. Most displaced persons have lost their homes, their land, most of their livestock, and their primary means of livelihood-agriculture. Those living in government-run Salwa Judum camps survive in cramped conditions and typically lack even the most basic sanitation and health care facilities. There are few opportunities for employment in the camps, leaving many residents with little or no income. While the Chhattisgarh state government initially provided regular free food rations to residents in some of the camps, in some instances those rations have been cut back or eliminated. Human Rights Watch also found that additional displaced persons live in unofficial settlements and so-called government permanent housing in Bijapur and Dantewada districts, which have access to fewer services than camps that are acknowledged by the Chhattisgarh government.

Villagers who fled to Andhra Pradesh also often live in dire circumstances. Many had no financial resources to purchase or rent land when they fled, and thus settled in forested areas. Saying that these settlements are illegal, Andhra Pradesh forest officials have repeatedly evicted villagers, often using excessive force and destroying their homes and personal belongings. One hamlet that Human Rights Watch visited has been destroyed nine or ten times since January 2007. Forest officials have forcibly relocated many displaced families without prior consultation with them. As a matter of policy, the Andhra Pradesh government denies to these displaced persons the benefit of government welfare schemes such as food subsidies and rural employment guarantees on several grounds, including that they are not "local residents."

The experience of some villagers from Etagatta illustrates the nature of the Salwa Judum campaign and its impact. Government security forces and Salwa Judum members raided Etagatta, a 50-household village in Dantewada district, in the summer of 2006. One eyewitness told Human Rights Watch that the attackers came without warning, beat villagers, and took away their belongings, including their livestock. Salwa Judum members and government security forces then burned all the 50 houses in the village. According to the eyewitness,

Salwa Judum people and police killed about 15 people from the village-5 women and 10 men. All of them were adults, about my age-in their 30s. They slit the throats of five people, one was a woman. I knew these five people well … There was no reason why they should have killed them. They attacked whoever fell into their hands … I cremated two of them. They raped and killed Ungi who was about 13 years old. They also repeatedly raped [name withheld]. First they raped her in the village and then they took her to the police station, raped her, and then released her.

The same villager reported that Salwa Judum members and government security forces also forcibly took about four men and ten women from his village. He said that while all the women later returned, the men did not. He never learned what happened to them.

Frightened, many villagers hid for several days in the jungle. Salwa Judum members and government security forces returned, found them there, and attacked them again. Finally, the villagers fled to Andhra Pradesh with the hope of reaching safe ground.

As soon as they settled in Andhra Pradesh, however, forest officials burned their hamlet, saying that it was illegal because it was located on forestlands. Describing the treatment meted out by forest officials in Andhra Pradesh, the villager said,

Forest officials used to beat us. About 12 to 20 of them would come in their vehicles, drag us out from our huts, and beat us. They beat both men and women, and abused us-"choothiya, bhosda, sala [derogatory terms], you have come here and cut forests." Sometimes, they used to come two or three times a day … They burned our huts about five or six times and each time we rebuilt them. Until we rebuilt the huts, we used to live under the trees in the forests.

Eventually, with the help of local residents, those displaced from Etagatta resettled to a safer part of Andhra Pradesh. However, much to their dismay, they found that Salwa Judum members from across the state boundary tracked them down. Salwa Judum members came to their new hamlet in mid-2007 in search of villagers from Chhattisgarh. The local sarpanch (village official) misled the Salwa Judum members by telling them there were no recent arrivals in the area. Still, displaced villagers from Etagatta live in constant fear.

Abuses by Naxalites

The Naxalites are responsible for numerous serious abuses. They claim to be leading a popular "people's war," including by seeking equity and justice for the poor, especially tribal communities. Nevertheless, their methods include intimidation, harassment, threats, beatings, looting, summary executions, and other punishment of villagers who either refuse to cooperate with them or are suspected of being police informers. They also forcibly demand money, food, and shelter from villagers, recruit children as soldiers for use in military operations against government forces, and use landmines and IEDs that have caused numerous civilian casualties.

Naxalites conduct public trials in what they call jan adalats (people's courts) to punish, including by execution, suspected police informers or alleged traitors. The accused are denied any right to legal counsel, independent judges, or right to appeal. Jan adalats are also used to target village leaders and wealthy landowners. For example, Naxalites bring landowners before such a court and ask them to hand over a portion of their assets for redistribution among poorer villagers; those that dare to oppose the ruling are beaten.

The most frequent complaint against Naxalites is their extortion of food and money. Some villagers reported that Naxalites forced them to donate food grains even when it left them unable to feed their own families. In other cases, Naxalites have threatened to kill villagers who refused demands for money. They also collect "fines" from villagers who refuse to attend their meetings.

Naxalites recruit and use children in military operations. It is CPI (Maoist) (a prominent Maoist political party) policy and practice to use children from age 16 in their army. Children between ages six and twelve are enlisted into balsangams (children's associations), trained in Maoist ideology, used as informers, trained in the use of non-lethal weapons like sticks, and gradually "promoted" to other Naxalite wings–chaitanya natya manch or CNMs (street theater troupes), sangams (village-level associations), jan militias (armed informers), and dalams (armed squads) before age 18. Some children who are able-bodied and fit are directly recruited into dalams. Children in sangams, jan militias, and dalams are trained in the use of weapons, including landmines.

Children in jan militias and dalams directly participate in armed exchanges with government security forces. Children in bal sangams, CNMs, and sangams do not directly participate in hostilities, but are nevertheless open to armed attacks by government security forces during anti-Naxalite combing operations. Naxalites attack and sometimes kill family members and friends of armed cadre members who desert.

Naxalites have retaliated violently against the operation of Salwa Judum. They have attacked Salwa Judum camps, killing many civilians. Individuals who participate in Salwa Judum, particularly Salwa Judum leaders and camp residents appointed as SPOs, are also vulnerable to Naxalite reprisals. Naxalite retribution against SPOs is particularly vicious. In some cases, Naxalites have reportedly mutilated the eyes and genitals of SPOs killed during their attacks.

Naxalites have abducted, tortured, and executed villagers whom they believed were Salwa Judum supporters or their family members. Villagers who left voluntarily or were forced into Salwa Judum camps fear being assaulted or killed by Naxalites in retaliation if they attempt to return to their villages. Human Rights Watch has information about 45 people who were killed for allegedly supporting Salwa Judum.

The Naxalites use landmines and IEDs frequently to attack government security forces. These attacks escalated after Salwa Judum began in June 2005. Between June 2005 and December 2007, Naxalites carried out at least 30 landmine and IED explosions, often using remote trigger mechanisms. Although these explosions are largely targeted against government security forces, they also killed and injured civilians on numerous occasions.

They have deliberately destroyed dozens of schools, ostensibly to prevent their use for police operations. Human Rights Watch gathered information about 20 schools that Naxalites destroyed, most of them after Salwa Judum started.

Key Recommendations: The need for protection and accountability

The Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments have an obligation to provide for the security of the population against crimes by Naxalites. However, government measures to maintain law and order must be in accordance with international human rights law. Instead of combining principled security measures with effective steps to address problems faced by tribal communities and the resentments that have made it easier for the Naxalite movement to recruit supporters, government authorities have subverted international human rights norms. Authorities have not only supported abusive Salwa Judum vigilantes but also have provided effective immunity from prosecution to persons responsible for abuses. This has perpetuated widespread human rights abuses for over three years, and has led to a growing displacement and humanitarian crisis, especially for tribal communities.

The internationally recognized United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (UN Guiding Principles) state that government authorities have the primary responsibility to establish conditions, as well as provide the means, which allow displaced persons to return voluntarily, in safety and with dignity, to their homes or places of habitual residence, or to resettle voluntarily in another part of the country. They also state that government authorities should develop resettlement and reintegration packages in consultation with the displaced population.

In keeping with its international human rights obligations:

- The Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments should take all necessary and appropriate measures to end unlawful Salwa Judum activities, end all government support to Salwa Judum, including the provision of weapons, and end all participation by government security forces in Salwa Judum operations, including raids and reprisals.

- The Chhattisgarh state government should initiate serious and independent investigations of individuals responsible for carrying out or ordering human rights abuses, regardless of rank, and prosecute as appropriate.

- Consistent with its constitutional obligation to ensure state compliance with the Constitution, the Indian central governmentshould call upon the Chhattisgarh state government to immediately investigate and prosecute individuals, including senior government officials, implicated in serious human rights abuses in Dantewada and Bijapur districts. The Indian central government should also express its willingness to conduct an investigation upon a request by the Chhattisgarh state government.

- The Chhattisgarh state government should end deployment of special police officers for paramilitary operations against Naxalites.

- The Indian central, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh state governments should ensure, in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles, that internally displaced persons are protected against attacks or other acts of violence, and that they are provided without discrimination, safe access to essential food and potable water, basic shelter and clothing, and essential medical services and sanitation.

- The Indian central, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh state governments should establish conditions for and facilitate the safe return or resettlement of camp residents and other displaced persons who voluntarily choose to return to their villages or relocate to another part of the country, and restore or provide government facilities in these villages.

- The Indian central government should ensure that Andhra Pradesh government officials immediately stop the destruction of IDP hamlets, illegal forced evictions, forced relocation of displaced persons, and confiscation of their property.

- The Indian central government should immediately develop a national scheme for identification, release, and reintegration of children recruited by armed groups or police, in consultation with governmental, nongovernmental, and intergovernmental organizations, and in accordance with the Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups.

The CPI (Maoist) party should immediately:

- End abuses-such as killings, threats, extortion, and the indiscriminate use of landmines and IEDs-against civilians, including individuals who have participated in Salwa Judum, camp residents who served as SPOs, and police informers.

- Issue and implement policies guaranteeing safe return for villagers who wish to leave Salwa Judum camps and return to their villages.

- Stop recruitment of children under age 18 into Naxalite wings including armed wings. Release all children and give those recruited before age 18 the option to leave.

II. Methodology

This report is based on research conducted by Human Rights Watch in Khammam and Warangal districts of Andhra Pradesh, and Bijapur, Dantewada, and Bastar districts of Chhattisgarh between November 2007 and February 2008. These locations are most affected by the conflict between Naxalites, Salwa Judum, and government security forces, and were chosen based on literature review and background interviews with independent researchers, local NGOs, journalists, and lawyers who had either studied the conflict in Chhattisgarh or assisted victims of the conflict.

During the course of the investigation, Human Rights Watch interviewed 235 people, including:

a)69 displaced persons who fled from 18 different villages from Bijapur and Dantewada districts, and settled in 17 villages in Khammam and Warangal districts;

b)71 camp residents (including former camp residents) from seven Salwa Judum camps and one government permanent housing site in Bijapur and Dantewada districts, including 50 civilians, three Salwa Judum leaders, and 18 SPOs;

c)10 former Naxalites including two former child dalam (armed wing) members.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 15 government officials in Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh, including the district collectors (the highest district-level administrative post) of Dantewada and Bijapur districts, the superintendent of police of Dantewada district (highest district-level police officer), the director general of police (highest ranking state-level police official) of Chhattisgarh, the divisional forest officer of Bhadrachalam division in Khammam district, and the sub-collector of Khammam district.

In addition, Human Rights Watch conducted 51 interviews with lawyers, local journalists, and representatives from local and international NGOs, including Vanvasi Chetna Ashram, People's Union for Civil Liberties, Forum for Fact-Finding, Documentation and Advocacy, Vanya, Gayatri Sangh Parivar, Bastar Tribal Development Society, CARE, MSF, and UNICEF (a UN agency).

Human Rights Watch had hoped to include the perspectives of persons arrested as suspected Naxalites, especially children, through in-person interviews. Unfortunately, this was not possible despite requests to the Dantewada police superintendent.

Due to security concerns, Human Rights Watch was unable to conduct interviews with villagers living in jungles and interior villages in Dantewada and Bijapur districts, and members of the CPI (Maoist) party. This report however incorporates the CPI (Maoist) party's position on the conflict by citing its press releases and its October 2006 letter to the Independent Citizen's Initiative, a fact-finding team from India.

Local NGOs providing services to villagers assisted Human Rights Watch in identifying victims and eyewitnesses to interview; we further developed contacts and interview lists through references from interviewees.

Most interviews were conducted individually, although they often took place in the presence of others. They lasted between one and three hours and were conducted in Hindi, Telugu, or Gondi, depending on the interviewee's preference. The Human Rights Watch team included researchers who are fluent in Hindi. In cases where the interviewees chose to communicate in Telugu or Gondi, the interviews were conducted with the assistance of independent interpreters selected by Human Rights Watch. Some interviewees reported information regarding their families, friends, and acquaintances. In the relatively few instances where interviews were conducted with several interviewees at once, they are cited as group interviews.

Cases of Salwa Judum and Naxalite abuses may be significantly underreported due to a number of methodological challenges, including villagers' fear of being identified, rightly or wrongly, as a Naxalite and therefore subject to interrogation or harassment by police, and, alternatively, their fear of reprisals by Naxalites or Salwa Judum members for reporting abuses.

Since most villagers keep track of time according to seasons, including agricultural seasons, in many cases interviewees were unable to give exact months for incidents. In some cases, interviewees described incidents with Indian festivals as time-indicators, or used their grade in school as a reference point. In this report, Human Rights Watch has in several cases provided approximate times based on such information from interviewees.

Human Rights Watch has used pseudonyms or withheld the names of almost all civilians, SPOs, and former Naxalites quoted in this report, consistent with our commitment to such individuals that their identity would not be revealed. Pseudonyms do not correspond to the tribe of the interviewee. Officials' names have been included where they gave permission for them to be used. Some NGO representatives requested that they or their organizations not be identified in order to protect themselves from reprisals by government and police, and identifying information has been omitted accordingly.

For security reasons, Human Rights Watch assured some interviewees that the location of the interview would not be disclosed. In this report, the names of most IDP settlements in Andhra Pradesh and some Salwa Judum camp names have not been disclosed, also at the request of interviewees who feared retribution.

The interviews have been supplemented by official data supplied by Chhattisgarh government officials in response to applications filed by NGOs or individuals under the Right to Information Act, 2005.

In addition to interviews with Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh state government officials, Human Rights Watch requested information regarding issues raised in this report in letters to state government officials, copies of which are provided in Appendix II. Human Rights Watch did not receive any substantive response to these letters.

Terminology

Unless otherwise specified, Human Rights Watch uses the phrase "government security forces" to refer to one or more of the security force units deployed in the region between June 2005 and June 2008: Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), Indian Reserve Battalions (IRBs), Chhattisgarh Armed Forces (CAF), and SPOs. It is virtually impossible for a civilian to clearly differentiate between the different types of police and other security force units and many interviewees used the broad term "police" to refer to these different forces. Human Rights Watch is not in a position to independently verify whether raids described by interviewees were conducted by the CRPF, IRBs, CAF, SPOs, or some combination thereof, and has therefore simply reproduced what interviewees told us.

Human Rights Watch found that some villagers who were forcibly relocated by Salwa Judum and government security forces are living in areas that are not recognized as camps by the government even though residents of these areas consider them camps. In this report, Human Rights Watch refers to such areas as unofficial camps.

In most places, this report refers to Dantewada and Bijapur districts that are now separate administrative divisions, each administered by a district collector. Until May 2007 Dantewada and Bijapur districts were part of one district-Dantewada, and administered by one district collector. Therefore, in some places, this report refers to Dantewada (undivided). It is important to note that most Indian fact-finding team reports were brought out before this administrative division; references to "Dantewada" in those reports would correspond to references to Dantewada (undivided) in this report.

Tens of thousands of people have been displaced from their homes by the conflict, either within Chhattisgarh, or into neighboring Andhra Pradesh or other states. Under international law, all are technically internally displaced persons (IDPs). However, government officials and others in the region typically use the term "IDP" to refer solely to individuals who have fled from Chhattisgarh into other states. This report follows this latter practice unless otherwise indicated.

Human Rights Watch follows the definition of child as given in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989; all references to children in this report are references to persons below age 18.

III. Background

In 2006 Prime Minister Manmohan Singh described the Naxalite movement in India as the "single biggest internal security challenge ever faced" by the country.[1] He also stated that Naxalism is not merely a law and order problem, noting that it is directly linked to problems of underdevelopment, exploitation, lack of access to resources, underdeveloped agriculture, lack of employment opportunities, and other factors.[2] Tribal areas, he pointed out, being largely excluded from most public services, are the most deprived, and form a breeding ground for Naxalism.[3] According to the 2007 annual report of the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs, the Naxalite movement has spread across 13 states in India.[4]

Naxalism in India

An armed peasant uprising in May 1967 in Naxalbari (West Bengal) marked the beginning of the Maoist revolutionary political movement in India. The movement is named after the region and thus called the Naxalite movement. Unlike the conflicts in Jammu and Kashmir and the northeast, which are self-determination movements, Naxalites call for a total transformation of the existing political system to create a new social order ending what they see as the exploitation of marginalized and vulnerable communities. Naxalites carry out their political agenda through various means including armed attacks against the state. There are many different political groups that believe in the Maoist ideology and identify themselves as Naxalites, but chief among them is the Communist Party of India (Maoist) (CPI (Maoist)).

Broadly, all Naxalite cadres operate underground and are organized into two components-an armed wing and a political wing. The political wing is headed by a national level central committee. Naxalites organize their activities in villages through underground village committees. The village committees, in turn, conduct their activities through sangams (village-level associations). A sangam is the village-level administrative unit that spreads Maoist ideology, aims to increase the Naxalite support base, assists the armed wing, and organizes jan adalats (people's courts).[5] Sangamschallenge and replace not only traditional tribal structures of village headmen and priests but also the gram panchayats (village-level councils of elected government representatives).[6] Naxalites also have street theater groups called chaitanya natya manch (CNM) that spread their ideology in villages.

The armed Naxalite wing consists of the standing army (the People's Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA)) and other smaller armed guerrilla squads that are assisted by groups of armed informers called jan militias. The army and guerrilla squads are generally referred to as dalams.

* * *

Naxalites wage a "people's war" not only by using methods such as organizing the poor to protest against exploitation, forcibly redistributing land, and opposing development projects that involve forcible displacement of marginalized communities, but also by attacking police stations to loot arms, destroying state infrastructure like railways, assassinating politicians, and extorting from businessmen.[7] These activities are crimes punishable under security and penal legislation in India.[8]

Until 2000 Chhattisgarh was part of Madhya Pradesh state in central India. The area that became Chhattisgarh is heavily forested, and home to some of India's indigenous tribal groups. Tribal communities make up about 32 percent of Chhattisgarh's total population,[9] and about 79 percent of the population in Dantewada and Bijapur districts in southern Chhattisgarh.[10] Maria Gonds and Dorla tribes are the two main tribal communities in this region.[11]

Naxalites commenced their activities in the Bastar region of Madhya Pradesh[12] in the 1980s.[13] A combination of political, economic, and social factors in this region, including economic exploitation of tribal communities, poor relations with the police, and absence of government facilities and state institutions, contributed to the popular support and growth of Naxalism.[14] For example, government authorities treated parts of Bastar region (especially Dantewada and Bijapur districts that are now part of Chhattisgarh) as remote administrative outposts or "punishment postings."[15] As one senior police official described it, "there is no administration in about 70 percent of this region [Dantewada and Bijapur districts], and only police have access to some parts."[16] The two districts (comprising of 1,220 inhabited villages) rank among the worst in India in terms of access to education and basic health care.[17] Census data from 2001 for these districts shows that there are no primary schools in 214 villages, and 1,161 villages have no access to health care.[18]

Prior to the Naxalite intervention, tribal communities living in this region had no rights or control over the forest, were forced to sell their produce to non-tribal contractors and money-lenders at low rates, and tribal women were at a high risk of sexual exploitation at the hands of money-lenders and contractors. Many observers believe that Naxalite initiatives resulted in improved living and economic conditions for many tribal communities.[19] The Naxalite agenda continues to include struggles for tribal rights to land, water, forest produce, better wages, health care, and education.[20]

While many villagers in Bijapur and Dantewada districts confirmed that Naxalites assisted tribal communities, they stated that their methods had gradually become increasingly authoritarian, undemocratic, and marked by human rights abuses including extrajudicial killings, beatings, and extortion.[21] Over time, this has created resentment among some villagers. Typically, the disaffected group consists of non-tribals, sarpanches (village official), village headmen, priests, and many people from the Dorla tribe, which is socially and economically better placed than the Maria Gond tribe.[22] Villagers who have been pressured to support Naxalites also say they have faced police harassment because they were perceived to be Naxalite supporters.

Naxalites have de facto control over large parts of Dantewada and Bijapur districts. With a network of sangams in this region, they have set up what they call janata sarkar (people's rule) and declared the Dantewada (undivided) area as a "liberated zone."[23]

Salwa Judum: Vigilantes to oust Naxalites

Since 2005 Dantewada and Bijapur districts have been the center of Naxalite-related violence in Chhattisgarh. In June 2005 some local protest meetings against Naxalites in Bijapur district sparked the creation of what is now known as Salwa Judum(literally "peace mission" or "purification hunt").[24] The Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments saw the protests as an opportune moment to challenge the Naxalite influence in the area. They provided support primarily through their security forces, dramatically scaling up these local protest meetings into raids against villages believed to be pro-Naxalite, and permitted the protestors to function as a vigilante group aimed at eliminating Naxalites.

Several government-run makeshift camps (also known as Salwa Judum camps, base camps, or relief camps) were started near police stations or paramilitary police camps along the highways, and many civilians were forced into these camps. The Chhattisgarh government, however, maintains that they started these "relief" camps to provide support to people who were fleeing Naxalite violence from villages:

The Naxalite problem has led to lack of security among large population of tribal [sic] and therefore State has constituted certain relief camps. The relief camps comprises [sic] of people who are either victims of Naxalite movement or fear the reprisals or attacks from Naxalite activities. The relief camps are only a State response to rehabilitate the displaced tribal as well as provide safety to tribal [sic] from fear of Naxalites. The relief camps are being constituted so as to discharge the constitutional obligation of providing security and safety to the tribal [sic].... The villagers have joined relief camps on their own volition.… There is no force employed on the part of the State to ask tribals to join the camps.[25]

Even though the Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments contend that Salwa Judum is a "people's campaign," there is evidence they actively promoted the creation of the groups. For instance, the 2005-2006 annual report of the Ministry of Home Affairs states: "The States have also been advised to encourage formation of Local Resistance Groups/Village Defence Committees/Nagrik Suraksha Samitis [Civilian Protection Committees] in Naxalite affected areas. In the year 2005, Chhattisgarh witnessed significant local resistance against the Naxalites in some areas."[26] The Dantewada (undivided) district collector's work proposal of 2005 illustrates how the Chhattisgarh government actively encouraged and assisted Salwa Judum. For instance, the work proposal states,

So far the people have been conducting the Abhiyan [campaign] on their own. The Naxalites are trying to dissuade them through persuasion or through threats. If they are not given support from the administration, the Abhiyan will die out.[27]

The work proposal also advocates arming tribal communities: "In addition to training the villagers, they should be given traditional weapons like bows and arrows, axes, hoes, sticks etc. Although most villagers already have such weapons, it would be good to encourage them by distributing ready made arrows or iron to make arrows."[28]

The Dantewada (undivided) district collector's memorandum of 2007 states that since June 2005 around 139 Salwa Judum padyatras (rallies) and 47 Salwa Judum meetings were held, and 644 villages from Dantewada (undivided) district "joined" Salwa Judum.[29] Indian NGOs and fact-finding team reports state that Salwa Judumwas able to operate on such a large scale because of the active support it received from the government.[30]

Deployment of government security forces

The Indian central government has deployed government security forces including paramilitary police such as the Indian Reserve Battalions (IRBs) and the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) to enhance security in these areas.[31]

In December 2007 Chhattisgarh police officials stated that there were 10,000 government security forces in Dantewada and Bijapur districts.[32] The 2007 annual report of the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs states that 13 battalions of central paramilitary forces have been deployed in Chhattisgarh.[33]

The Chhattisgarh government also raised an auxiliary police force of special police officers (SPOs) and reportedly is planning to convert this auxiliary police force into a regular battalion to counter Naxalites in the region.[34] The Police Act, 1861, empowers a local magistrate to temporarily appoint civilians as SPOs to perform the roles of "ordinary officers of police."[35] SPOs enjoy the same powers as the regular civil police,[36] but receive less training and fewer benefits.[37] The law allows for the appointment of civilian SPOs as a stop-gap measure where the police force is otherwise felt to be insufficient. It does not permit a local magistrate to deploy SPOs either indefinitely or in roles comparable to those played by paramilitary police such as the CRPF and the IRBs.[38]

The Chhattisgarh government started implementing the SPO program around June 2005.[39] There are some 3,500-3,800 SPOs in Dantewada and Bijapur districts.[40] Most SPOs are tribal camp residents (including children) and surrendered sangam members who are familiar with the jungle trails in interior forested areas and are therefore useful to the government security forces in their anti-Naxalite combing operations.[41] A senior human rights lawyer contends that the Chhattisgarh administration has misused section 17 of the Police Act, 1861, that states that civilians may be appointed as SPOs for "such time and within such limits" in cases where "the police-force ordinarily employed for preserving the peace is not sufficient":

The Indian Police Act does not envisage en masse recruitment of SPOs.… The wholesale arming of a social group to exterminate its enemies is not what is envisaged by sec. 17 of the Police Act, 1861. What the Chhattisgarh Government has done is to blatantly abuse the provision.[42]

Civil society challenges to a failed policy

The Indian central government now admits that Salwa Judumexacerbated the Naxalite conflict and violence in the region.[43] Several fact-finding teams and NGOs have repeatedly reported that Salwa Judum members and government security forces were using violent intimidation methods resulting in massive forced internal displacement, and have recommended that the Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments stop supporting Salwa Judum.They have also recommended that the governments initiate action against all persons involved in committing crimes.[44] Activists also filed two petitions in the Supreme Court of India in 2007, seeking the court's intervention against the operation of Salwa Judum.[45] In April 2008 the court ordered the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to investigate allegations of human rights abuses by both sides.[46]

NGO fact-finding teams have also appealed to Naxalites to end their violent backlash against Salwa Judum.[47] Many human rights groups and activists are making an effort to bring together a group of respected and neutral citizens who can mediate between the government and Naxalites to end this cycle of violence.[48]

IV. Abuses by Salwa Judum

From the escalation of the conflict in June 2005 until mid-2007, Salwa Judum leaders typically spearheaded its activities with the support of government security forces. Salwa Judum leaders mostly consist of people aggrieved by Naxalite activities-contractors or middlemen, members of non-tribal and landed tribal communities, sarpanches (village officials), patels (village headmen), and priests.[49]Salwa Judum members-ordinary tribal and non-tribal civilians, including children-carried out their leaders' instructions and conducted operations along with government security forces. They travelled from one village to another, particularly to villages that they believed were Naxalite strongholds, conducting violent raids, combing them for Naxalites, evacuating villagers to government-run camps (also known as Salwa Judum camps, base camps, or relief camps), and in some cases, beating, raping, and killing villagers.

During this period, Salwa Judum members and government security forces used a range of coercive techniques to force civilians to participate in Salwa Judum meetings or to relocate them to camps. They routinely claimed that villagers who did not join Salwa Judum must be Naxalites. On many occasions, they also carried out reprisal measures against camp residents who returned to their villages or against persons who fled from Chhattisgarh and settled in Andhra Pradesh.

The Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments deny providing support to Salwa Judum.[50] The Chhattisgarh government has maintained that:

The 'Salva Judum' movement is people's initiative and it is reiterated that 'Salva Judum' is notState sponsored. The State is committed to resolve the problem of Naxalism and any peaceful movement, which resists the violent methods, definitely gets support of States.… Salwa Judum is not a vigilante force but a spontaneous people's resistance group comprising of local tribals. The State cannot stifle the people's initiate [sic] taken by local tribals to counter Naxalism.[51]

In our research, however, we found overwhelming evidence of state support for Salwa Judum. Government security forces either actively participated in Salwa Judum abuses or, despite being present at the scene, failed to prevent Salwa Judum members from committing abuses. In fact, the chairperson of the second Indian Administrative Reforms Commission (a commission of inquiry set up by the president of India) criticized the Chhattisgarh government for delegating its law and order powers to an "extra constitutional [prohibited by the Constitution] power" like Salwa Judum.[52]

While there is evidence that joint raids by government security forces and Salwa Judum members have been on the decline since mid-2007, the practice has by no means ended-reprisals against villagers who leave camps are ongoing. The Chhattisgarh state government claims that it upholds the rule of law. However, over a three-year period starting mid-2005 it has shown little willingness to directly take on Salwa Judum as an abusive vigilante force and prevent government security forces from participating in such abuses.

Under international law, the Indian central and Chhattisgarh state governments are ultimately responsible for the lives and well-being of the population. Internationally recognized human rights set out in core human rights instruments guarantee all people equal and inalienable rights by virtue of their inherent human dignity.[53] Under these instruments, the state as the primary duty holder has an obligation to uphold these rights. This includes not only preventing and punishing human rights violations by government officials and agents, but also protecting communities from criminal acts committed by non-state actors such as Salwa Judum members.

India is party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), one of the core international human rights treaties. The Human Rights Committee, the expert body that monitors compliance with the ICCPR, has observed that a state party's failure to "take appropriate measures or to exercise due diligence to prevent, punish, investigate or redress the harm caused by such acts by private persons or entities" itself constitutes a violation of the ICCPR.[54] Similarly, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary, or Arbitrary Executions has observed that when "[a] pattern [of killing] becomes clear in which the response of the Government is clearly inadequate, its responsibility under international human rights law becomes applicable. Through its inaction the Government confers a degree of impunity upon the killers."[55]

A. Salwa Judum raids on villages coercing civilian participation

Human Rights Watch interviewed 52 individuals who were eyewitnessesto Salwa Judum raids on 18 villages in Dantewada and Bijapur districts. Each of these villages had been destroyed or vacated due to Salwa Judumraids since June 2005. These persons also gave Human Rights Watch a list of 26 additional villages that they said were burned by Salwa Judum members.[56] A petition filed in the Supreme Court of India estimates that between June 2005 and August 2007 Salwa Judum members and government security forces killed 537 villagers, burned 2,825 houses, and looted many thousands of other houses in Dantewada and Bijapur districts.[57]

All the eyewitnesses to Salwa Judum padyatras (rallies) in their villages stated that these were violent events aimed at either enlisting their participation in Salwa Judum meetings or relocating them to camps.[58] The coercive tactics ranged from threatening and imposing fines, to beating, abducting, and killing villagers, and burning and looting hamlets (See Appendix I).

According to some villagers, during Salwa Judum's most active period, between June 2005 and the monsoon season of 2007 (June to September), Salwa Judum members and government security forces conducted raids on their villages at least two or three times every month, and sometimes every day. Eyewitnesses estimated that they came in numbers varying from 50 to 2,000.[59] For instance, describing the number of people who raided his village, one local resident pointed to a field approximately the size of a soccer field and said, "this entire field was filled with them [Salwa Judum members and government security forces]."[60] During such raids Salwa Judum members were usually armed with sticks, axes, daggers, spears, and bows and arrows, while government security forces were armed with rifles.[61]

Sometimes the raid was preceded by a mandatory Salwa Judum public meeting. Explaining why her family members attended Salwa Judum meetings, Vasanti Kumar said,

Judum people told them [family members] that everyone should go for the meeting or else they will have to pay a fine of 500 rupees [roughly US$12] for each member in the family. My sisters and mother had no money so two of my sisters went for the meeting.[62]

A woman from Kothooru described how Salwa Judum members and government security forces came to her village, beat her, and forcibly took her to a Salwa Judum meeting.[63] Another woman from Neeram attended a meeting because Salwa Judum leaders had given a letter to a local sarpanch stating that if they did not come, then their village would be attacked.[64] One villager from Nambi described how Salwa Judum and government security forces went to the weekly market and intimidated villagers into attending meetings or relocating to camps.[65]

In these public meetings, Salwa Judum leaders appealed to villagers to join Salwa Judum to fight Naxalites. A teenage boy who attended the public meeting in Basaguda in June 2006 recounted the speeches at these meetings:

[They used to say,] "We [Salwa Judum] won't keep Naxalites in this country. We will chase them away to another country. We will all form Salwa Judum together and chase Naxalites. Come and stay with us in the camps to help us fight Naxalites."[66]

Sometimes senior police officials, administrative officials, and politicians attended these meetings.[67]

In some cases Salwa Judum members took away children and adults (both male and female) to attend meetings. In some others they took away only men and boys, leaving behind women, girls, and young children. Sometimes people who were forcibly taken to attend meetings were prevented from returning-to force the family to relocate to Salwa Judum camps. Explaining how the men who were taken away did not return, Mihika said,

I waited for my husband to come back but he did not return at all. He was taken to the camp [by Salwa Judum] about two years ago [in 2005]. So I ran away and came towards [name of place withheld] thinking it would be safer here.[68]

Mihika left her village and moved to another village with her five children who were all under age eight. She did not know where her husband was for a long time. She said that her husband eventually managed to escape from the camp and came looking for his family.[69] Several other people interviewed by Human Rights Watch described similar experiences.[70] Kaskul Naiyya said,

They [Salwa Judum and CRPF] forced all the men to go with them [for the meeting], including boys. Judum took away boys his age [pointing to a boy who said he was about age 13] as well. If there were no male members in the house, then they would take the woman from that house. The people they took did not return home.[71]

Naiyya's brother, age 17, who was forcibly taken away along with her uncle to attend a meeting, returned after a few days and told them that they had been taken to a Salwa Judum camp. But her uncle was prevented from returning.[72]

Salwa Judum members harassed villagers who did not voluntarily relocate to camps. For instance, one strategy was to cut off villagers' access to the weekly market.[73] One villager said,

People from Neeram are not allowed to cross the [Indravati] river anymore-even to go to the market. They have to go all the way to Naranyanpur market, which is a two-and-a-half-days' walk.[74]

A villager from Lingagiri described how after a Salwa Judum meeting in Lingagiri in early 2006, government security forces asked all villagers who had not relocated to the Basaguda camp to report at the police station every day. He said,

After the meeting, we had to go to Basaguda police station everyday. One member from each family had to go everyday and report that we are still there [and had not joined the Naxalites]. The timing for reporting was fixed-around 8 to 9 a.m. If we didn't go, the other villagers would be questioned and when we went the next time we would get threatened and beaten by Salwa Judum members. Even if we were sick we had to go and report in the police station if we didn't want to get beaten the next time.[75]

Typically, if villagers refused to relocate to camps despite threats and harassment, then Salwa Judum members and government security forces used other coercive techniques-they terrorized civilians by beating or abducting them, taking away their livestock, and burning huts and at times entire villages.

Raids on villages usually came without warning. "As soon as Salwa Judum members and CRP people [CRPF] entered the village, they started beating people and setting huts on fire. They didn't make any announcements or give any orders [to vacate the village]," said Vachcham Ragu from Sankanpalli.[76]

Describing an attack by Salwa Judum and government security forces on Pidmel, one villager said,

Judum came to my village along with SPOs [special police officers] for the first time in summer last year [2006]. They came and surrounded the entire village. Some of us managed to run into the jungle before they surrounded the village and some got caught. Those who got caught got beaten severely. They came three times to our village. First two times they beat people. The first time they came they also burned eight huts. My hut was not burned. Though they took away all the livestock-the poultry and goats. I lost three goats. They also looted all my utensils, our clothes, blankets, and barrels.[77]

In many cases Salwa Judum members along with government security forces killed civilians and raped women to terrorize them and force relocation. Human Rights Watch received reports from villagers of approximately 55 killings of family members, friends, or acquaintances but was not able to independently verify every case.[78] While most villagers typically fled at the first sign of a Salwa Judum raid, they sometimes returned to their villages to find bodies of people who were not able to escape.

A villager from Kamarguda explained how he cremated others from his village, and fled for safety:

There were around 50 huts in my village and all were burned by Salwa Judum members and police. They also killed three people-slit open their throats. [When we were fleeing] they [Salwa Judum members and government security forces] caught them [others from his village] in the jungle and then took them. Don't know where. I don't know where they killed them; maybe they killed them in the police station. But later we found their bodies in the Jagargonda jungle. Some of us found the bodies and cremated them. We found Mandavi Podiya's (age 70), Mandavi Budra's (age 40), and Mandavi Unga's (age 30) bodies. I left the next day.[79]

Villagers from Mukudtong described a raid on their village "immediately before dusshera [an Indian festival in September-October] in 2006":

Judum and police came to our village. They came in three or four trucks, and many more on foot.… Came and burned our village-about six huts were set on fire. The very first time they came, they came early in the morning-something like They first burned some huts and then announced that if we did not vacate our village and go to Injeram camp this would be the fate of everyone in the village, and that they would burn all the huts .… They also beat the sarpanch [village official] and the poojari [priest]. They beat others also. The people who came to our village had bows and arrows, sticks, and the police had rifles. From our village they also raped [name withheld] (about age 20). They raped her and left her in the village itself.[80]

Salwa Judum members came back again and burned their entire village. They continued,

Judum members came again after a month in the afternoon. This time they killed Madkam Adma (age 50). They shot him and stabbed him. Adma was in his house when this happened. They burned the entire village. The second time people came on foot only-Judum with SPOs and CRP police [CPRF]. SPOs were wearing police uniforms.[81]

The villagers said Mukudtong was not close to the road, making access difficult. Villages that were close to the roads had it worse, they said:

In Kotacheru they used to go almost every day because it was very close to the road. They killed five to six people. One of them was the patel [village headman]. His name was also Madkam Adma. We don't know the other names. [We heard that] they [Salwa Judum members and government security forces] raped many women from Kotacheru but we know only one of them who was raped-her name is [name withheld] (about age 22).[82]

Villagers also reported that Salwa Judum members abducted many people from markets and took them to camps. One villager from Toodayem said,

I had gone to the Matwada bazaar one day last year [2006] and Judum people saw me in the bazaar, caught me, and started beating me. They beat me with chappals [slippers] and lathis [sticks] on my face and back. I have lost my hearing in one ear after this. They kept screaming "Sala [derogatory term] you are with Naxalites and you are supplying them with food." And they were saying to each other "Let's slit his throat and throw him in the gutter." They dragged me to the Bhairamgarh camp. I had no extra clothes or food.[83]

Another villager from Tolnai said Salwa Judum members abducted around 15 people from his village who had gone to the weekly market in Errabore during the harvest season in 2006, and took them to Konta camp.[84]

In some cases, villagers "disappeared" after they were forcibly taken away by Salwa Judum members or government security forces: their relatives had no further information about them. Kadti Gowri from Nendra said that in February 2006 Salwa Judum members and government security forces forcibly took her to Errabore camp along with three others-her son-in-law, and his brother and father. The last she saw them was near a river behind Errabore camp. She said that she had searched for them, had not found them, and still did not know their whereabouts at the time of her interview with Human Rights Watch in December 2007. She fears that Salwa Judum members or government security forces may have killed them.[85]

B. Coercing camp residents' participation in Salwa Judum

Not only were villagers forcibly evicted from their villages and moved into camps, but once in the camps, they were coerced into participating in Salwa Judum's activities, which included attending meetings, going on processions, and even raiding other villages. One former resident of Mirtur camp narrated the trauma of camp residents:

All able-bodied men had to participate in all Salwa Judum's processions-even 12-year-olds had to participate in Salwa Judum's meetings.… We had to also go with them to burn our own village. We could not say no because then we would get beaten brutally. We were very scared of them and were sure that we will be beaten if we refused to go with them on such processions. They used to also force us to carry weapons on these processions. And the people who did not go got beaten severely.[86]

A former resident of Errabore camp described the hierarchy and rules in the camp. She said,

When Judum members want to go to a village or have a meeting, … the sarpanch either asks everyone to go or says that one member from each family [at the camp] should go. My father used to go from our family. When they announce that villagers should go with them to other villages, they also announce that whoever is going should carry weapons with them-whatever they have in their homes-axes, sickles, sticks, whatever. If some family does not go for these meetings or rallies, then the supply of provisions to the family is cut off.[87]

Another former resident of Geedam camp (now Kasoli camp) complained,

During that time [our stay in the camp], the government did not give us anything to eat-no [food] rations-nothing. On top of that, they would ask us to go for meetings and rallies. Imagine being hungry and going for these meetings. Some people refused and got beaten severely. All youngsters, that is, able-bodied men were supposed to go for these meetings and we had no choice.[88]

One resident from Jailbada camp tried to escape but was caught, brought back to the camp, and forced to attend Salwa Judum's meetings and rallies. Narrating how he was routinely harassed, he said,

[W]hen I tried going back, the police caught me, brought me back, and beat me. I have to go for meetings and rallies with Judum members. If I do not participate, then they [government security forces] drag me out of the house and say "Go back to your village" and force me to leave; or they threaten to beat me. Then if I go back [to the village], they come looking for me, beat me, and bring me back.[89]

C. Salwa Judum reprisals against villagers who leave camps

Many camp residents return to their villages during the day to restore their homes and cultivation. Some flee from the camps and attempt to return to their villages permanently.

Salwa Judum leaders from Dantewada told Human Rights Watch that "villagers are free to go wherever they want."[90] Several government officials also stated that camp residents are free to leave and return to their villages. The Dantewada Superintendent of Police Rahul Sharma assured Human Rights Watch:

It [the camp] is not a concentration camp and no one is forced to come here. People have been living in the camps for the last two years, but hardly anyone has gone back to their villages. It's all free. Anyone who wants to, can leave. They stay because of the government services.[91]

Another police officer from Dantewada stated,

We advise villagers not to go to their villages out of concern for their security. If they tell us in advance that they want to go, we will provide them with escorts. We go with them whenever they want to celebrate festivals in villages. But when they go to the villages without telling us it becomes a problem.[92]

The Dantewada district collector said the same, "People in the camps are free to go back to their villages, free to go anywhere at any time."[93]

These statements were contradicted by many camp residents who described reprisals for attempting to return to their villages. Salwa Judum members and government security forces have carried out reprisal measures against villagers who left camps. One former resident of Mirtur camp said that any attempt to leave the camp was viewed with suspicion. He said,

People were not allowed to go to their villages. If we went to our villages and came back then we were beaten. If there was an attack on police anywhere, then we would get beaten. Judum leaders and SPOs beat us. They would call us for a meeting and when we were in the meeting they would start beating us. We used to get beaten severely at least once every week. They used to beat us with big sticks. Only the men were beaten and they used to say that we were also part of the group that attacked the police.[94]

These reprisals are ongoing. Describing a Salwa Judum attack on their village a week earlier in December 2007, the former resident from Mirtur camp said:

Last Monday, Judum members came to our village and burned all the grain that we had harvested. They also beat a woman-they beat her with an axe. Even after we left the camp, Judum members used to keep coming to our village and take away our livestock. We do not stay in our village. We keep going back and forth between [village name withheld] and [village name withheld] to avoid Salwa Judum whenever they come.[95]

Some residents who went to their village every morning to cultivate their fields described an attack on them in December 2007,

Salwa Judum members from another village came a week ago and started beating people. They said, "We are staying in camps far from our villages. You are staying close to your village and go back and earn a livelihood [by cultivating your fields]. But we can't do the same." They threatened to pull roofs off the houses in the camp. The police, Salwa Judum, SPOs-all came. SPOs and CRP people [CRPF] beat us. They came in a large number-looked like a thousand. They beat 12 to 15 people.[96]

D. Salwa Judum reprisals against villagers who have fled to Andhra Pradesh

Salwa Judum and government security forces also cross over to Andhra Pradesh searching for people from Chhattisgarh who have settled there. In one case, they went to a village in Andhra Pradesh and abducted two men who had fled and settled there in February 2006. Eyewitnesses to the incident said that Irma Madan and Irma Vandan are brothers who were residing with them in the hamlet. Madan went to Surpanguda (in Dantewada district) in October 2007 to meet his cousin. His cousin then brought Salwa Judum members and government security forces to their village (in Warangal district) in search of Madan and his brother. The villagers said,

Around November 14 or 15 [2007], his cousin came along with Salwa Judum and police. About 40 or 60 Salwa Judum and police came at night-7 or 7:30 p.m. Police stayed at the checkpost. He [the cousin] came to the village with Salwa Judum. Salwa Judum people stood over there [pointing to a location about 100 yards away]. He walked into the village with a bag and asked for Madan, and met him. Then he asked to go to the toilet and when he went out he came back with Salwa Judum people. They surrounded Madan and took him. Then they did the same to his brother. All the villagers were alerted only as Madan's wife started screaming. They left their wives and children behind and only dragged away the men … The brothers fell at the feet of Salwa Judum people and begged not to be taken but they were beaten and dragged. We couldn't go to their rescue because there were so many of them and we were so few of us. We were also very scared-Salwa Judum was armed with machetes and knives, and the police had big guns…. We still don't know what happened to them.[97]

The fear of reprisals is so high that people who have settled on the Andhra Pradesh side said that they hide and run when they see Salwa Judum members. A member of a group of displaced persons said,

We have seen Judum and can even identify some of them because they are from neighboring villages from Chhattisgarh. These people usually come on motorcycles or in autos [rickshaws] and cover their faces with towels-so we cannot tell whether they are SPOs or Salwa Judum because sometimes SPOs also wear clothes like ours.[98]

One of the displaced persons continued,

Judum members identified me and asked me where I live. I told them that I do not live here and I come here for agricultural labor and go back. I did not want to tell them where I lived because I was scared they would come here and do the same thing. This happened one month ago [in November 2007].[99]

V. Abuses by the State

Although the director general of police (DGP) of Chhattisgarh stated that government security forces attend Salwa Judum rallies "because they have to be protected,"[100] nearly all of the people who reported Salwa Judum raids on their villages said that government security forces participated in the burnings, killings, and beatings.

When NGOs and human rights activists have brought to light human rights abuses and violations since mid-2005, the government has questioned the authenticity of their reports and largely ignored them, allowing human rights abuses and crimes to be perpetrated unchecked.[101] Chhattisgarh officials, including state police, have repeatedly harassed journalists and activists who reported such violations and abuses.

A. Killings, beatings, burnings, and pillage

Villagers consistently said that government security forces routinely participated in Salwa Judum raids through late 2007 and a number said that these security forces were still participating in reprisals up to the present.[102] A displaced person from Nayapara said, "Every day police used to come, beat us, threaten us, kill people, that's why we got frightened to death and ran here [Andhra Pradesh]."[103]

Lohit Rao's account of a raid by government security forces in Boreguda

Lohit Rao, age 37, from Boreguda, described to Human Rights Watch a brutal attack on his village and family. Rao said that Salwa Judum members began visiting Boreguda in 2005, together with government security forces (Boreguda falls under Basaguda police jurisdiction in Bijapur district). While, over time, Salwa Judum members stopped coming, government security forces continued to raid his village. The last raid that he witnessed was in December 2006. He fled to Andhra Pradesh after that.

Rao told Human Rights Watch,

On December 29, 2006 at about 5:30 a.m.… SPOs [special police

officers] killed my father. That is, the new ones that have recently

joined the police. They beat him with the rifle butt on his genitals

also.… I was hiding and watching.

We have two houses.… We had woken up and I was starting the

fire [for heat] when they came and surrounded our village. They

burned everything. If I tell you what all they took and burned, you

will run out of paper and ink.

They were asking my father to take them to the Naxalites.… Then

they brought my sister out and beat her. Then they beat my

mother. They took her [sister] to the fields and raped her. She

was 18 years old. I could hear her screaming. I was so scared I

didn't come out of my hiding place. I knew that if I came out,

they would kill me also. Later, we found her body near the fields.

They had put a gun in her mouth and shot her.…

About eight of them barged into my [other] house. We had so

many utensils-enough to fill up a tractor. They took all of that

and burned it.… On the same day they killed two others. Poojari

Motiram and Poojari Ramaiah.… We found two bodies-Motiram's

and my sister's in the fields. My father's in front of my house and

Ramaiah's behind his house.… They burned about 22 huts in

Boreguda….

I know they were all SPOs because they were wearing khaki

uniforms. They were few CRPF [Central Reserve Police Force]

wearing the uniforms with flowers [camouflage]. I don't know how

many SPOs and how many CRPF.[104]

On another occasion Lohit helped save a villager who was attacked by government security forces:

On another day- this is before my father and sister were killed

-they [government security forces] attacked another man

[name withheld] who was taking his cattle to the fields. He was

taken to the forests and they attacked him several times with

daggers. He was stabbed on his chest, neck, palm, hand, and

shoulder. They thought he died and left him there.

[He] had gone with his two children to the fields. The children left

the cattle, ran to the village, and told the villagers that the police

had come and were beating their father. So around 20 villagers

went to look for him. I was also there. We found him, put him in a

bullock cart, and brought him to Cherla.… They kept him in the

hospital for four days and then shifted him to Bhadrachalam

hospital. We spent 5,000 rupees (roughly US$125). He survived

the attack and now lives in Andhra Pradesh.[105]

A villager from Surpanguda narrated how government security forces came in helicopters and set his village on fire:

There are around 250 huts in my village, in different clusters. One year ago when I was staying there, the police came to my village- approximately in August 2006. They came and set fire to around 26 houses. I was there when the huts were set on fire. But because my village is very big and is in clusters, my cluster was not set on fire…. But I could see what was happening from my side. The people from the village started running as soon as they heard helicopters approaching and landing. Police came in three helicopters, landed there, and set huts on fire….

The police again came a second time in October this year [2007] and set huts on fire. This time they did not come in helicopters. They came by foot, and set fire to about eight huts.[106]

Some SPOs interviewed by Human Rights Watch also reported that government security forces participated in Salwa Judum raids. One SPO lamented how tribal communities were suffering because of the fighting: "Salwa Judum and police attack villages and burn them. It is sad because the Judum and police also kill adivasis [tribal communities] and Naxalites also kill adivasis. From both sides adivasis are getting trapped."[107] The SPO maintained that he had not joined these raids.[108]

When Human Rights Watch asked to speak with SPOs who had accompanied Salwa Judum members to villages, one police official made an announcement among SPOs inquiring which of them had gone to villages to burn them and bring villagers to camps.[109] Two SPOs came forward to share their experiences. SPO Kadti Soman said that he had gone with Salwa Judum members and government security forces to Uddinguda, Barraimuga, Birla, Gaganpalli, Ikkalguda, Kattanguda, and Darbaguda villages but was reluctant to elaborate on what SPOs had done in these villages.[110] He said, "We brought them [villagers] here [to the camp]."[111] Similarly, SPO Mandavi Mohan stated that he had gone with government security forces to Nendra in mid-2007 to "bring" villagers to the camp.[112]

Two other SPOs admitted to playing a role in starting the Jagargonda camp. One said, "I helped in starting the Jagargonda camp. We took the police and Judum there-we would go at around 3 or for patrols and gather people. About 40-45 of us would go each time and bring people to the camp."[113] Another SPO stated, "Judum and police from Dornapal took people from Miliampalli, Kunded, Metaguda, Kodmer, and Tarlaguda to the Judum camp in Dornapal. I was part of them."[114]