A late-night fast-food run led to a nearly 5-year ordeal for Jason DeFriese, a college junior who was stopped for speeding and charged with driving under the influence in March 2013. Jason was put on probation, administered by Private Correction Services (PCS), a private probation company in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. He and his family spent $10,000 on probation-related costs.

A number of states allow private probation companies to supervise probation for minor crimes, such as traffic offenses. These companies make all their profits from the people they supervise, and have a financial interest in keeping people on probation for as long as possible, Human Rights Watch found in a new report, “Set up to Fail.” The fees associated with private probation can be insurmountable, especially for people living in poverty, forcing them to sacrifice things like adequate food and housing to pay their probation company.

The arresting officer who pulled Jason over for speeding suspected he was intoxicated, but Jason said he had spent the evening playing intramural softball with friends before deciding to stop for food on his way home. Recalling the advice of a family lawyer, he refused to take a breathalyzer test. The officer arrested him and charged him with speeding, and because he refused a breathalyzer, an automatic driving under the influence (DUI).

At Jason’s hearing, the court dropped the speeding charge and deferred sentencing for the DUI. He was placed on “suspended imposition of sentence” probation, meaning that as long as he did not violate the terms of his two-year probation, the case would be closed without a conviction on his record. PCS, the probation company, would supervise Jason.

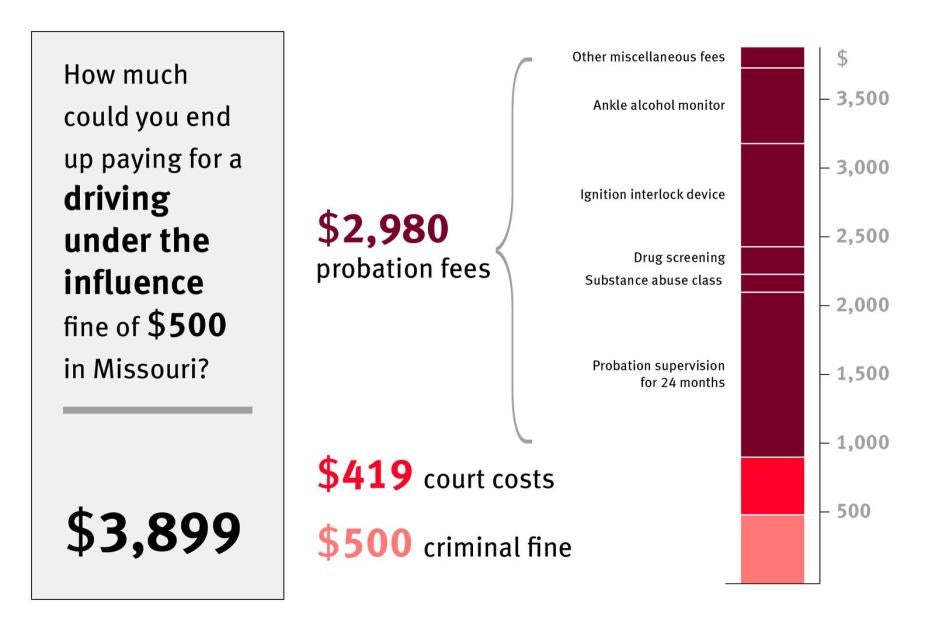

The court required him to pay $418 for court costs and another $310 for miscellaneous fees. He was required to avoid all illegal drugs and alcohol, complete a substance abuse traffic offender program, complete 40 hours of community service, and pay for periodic drug tests and monthly supervision fees of $50. He would also have to have an ignition interlock device installed on his car for nine months to be able to drive, for a total cost of just over $1,000, and pay any other fees that PCS might assess.

Jason graduated from college a few months after his probation began, moved home to St. Louis, and began working at a fitness center. PCS would not let him report to a local agency, so he drove two hours to Cape Girardeau every month to check in with his probation officer.

Eight months into his probation, Jason’s ordeal took a turn for the worse. The PCS probation officer decided to run a random drug test, which came back positive for alcohol. Jason says he hadn’t been drinking, and his results would not have been flagged as a violation by the state-run laboratory that uses a higher cutoff point to avoid picking up incidental exposures. In fact, Jason’s job at the fitness center meant that he was consistently exposed to alcohol-based cleaning products, and he also used alcohol-based hygiene products, like mouthwash, which may have contributed to a positive result.

Although the state lab would not have considered Jason’s result a violation, the court found that Jason had violated the terms of his probation. The judge told Jason that if he violated his probation again, he would go to jail. Then, the day of the hearing, Jason’s probation officer told him to provide another urine sample. This time, Jason tested positive for both alcohol and marijuana.

“I was shocked, I was about to have a breakdown,” Jason said. “I told her I wanted to retake the test, but she wouldn’t let me.” Fearing what they believed might be another false positive, Jason’s father immediately drove him to a private lab to retake the test. It came back negative, but that didn’t change the court’s decision.

This time, the consequences were more severe: His conviction went on his record, and the judge sentenced him to 60 days in jail and a $500 fine, which was suspended but with a new two-year probation sentence. Jason served four days in jail, for which he paid $90 in jail boarding fees, and was ordered to wear a continuous alcohol monitoring device for 90 days. PCS installed and monitored the bracelet, which cost $91 every week. Jason drove the two hours to their office in Cape Girardeau every week so PCS could download the information from the bracelet. But in order to drive, Jason also had to again install an alcohol ignition interlock system on his car, which cost an additional $671 over three months.

In the meantime, Jason’s probation officer also placed him in an intensive drug testing program, which required him to call a testing center at 8 a.m. every day to see if he had been selected to take a drug test. Every day, two colors were selected for testing; Jason’s color was green. If his color was selected, he would have to report to the testing center later the same day for a drug test. On some occasions, he heard his color called on two consecutive days. Jason’s family paid anywhere from $46 to $96 per test. Every one of his tests during the 18-month period was negative.

“It would be once a week, or sometimes two times a week, but it felt like it was every day,” Jason said. “I get it if you go in once a month, but I had an interlock in my car, I had an ankle bracelet on, how much testing does it take to realize that I’m not on drugs?”

The daily call-ins made it difficult for Jason to continue working. He eventually resigned from his job at the fitness center, as he couldn’t continue to ask for time off to take a drug test or visit his probation officer.

“Thankfully, I had the support of my parents,” Jason said, but “I was thinking about other people, how would other people do it?”

Jason and his family were paying a hefty price for probation and all its requirements. Jason’s father even created a spreadsheet to document the expenses, including 68 drug tests. When, after 90 days without any incident, Jason requested the removal of the alcohol monitoring bracelet, his probation officer wrote a note to the judge expressing reservations about Jason’s ability to stay sober without the bracelet. The judge denied the request and Jason wore and paid for the bracelet for an additional five months, which, at $91 per week, netted PCS approximately $1,820. His alcohol monitoring device never showed any violations.

Jason completed his probation in October 2017. His dream is to manage a parks and recreation department, and he wonders where he’d be if he hadn’t had to quit his job. But he recognizes that he’s luckier than many others, whose families wouldn’t be able to support their children financially through thousands upon thousands of dollars in probation fees.