Valentine’s Day is coming up and you may be thinking of giving your partner a piece of jewelry, or of helping to pick one out yourself. As you think about what you like and can spend, add this to your considerations: Where does the jewelry come from, and under what conditions were the minerals mined? Because these conditions can be ugly.

Take for example the widespread use of toxic mercury to process gold in small-scale mines, causing catastrophic pollution. When I visited a mining village in the Philippines, I saw the mercury-contaminated liquid flowing straight from processing mills into a shallow river in which children were standing to pan gold, or playing, or crossing to get to school. Mercury causes damage to the nervous system and is particularly harmful to children.

Some children who work in gold mining also use mercury to separate out the gold, unaware of its health effects. Fifteen-year-old “Aileen” told me she suffered regular spams, which can be a symptom of mercury poisoning: “I mix the mercury with my bare hands… I get spasms in my hands and my legs. Sometimes my hands feel like they are swollen.”

We have also documented serious human rights violations in diamond and gold mining. Children have been injured and killed when working in small-scale gold or diamond mining pits. Whole communities have faced ill-health because nearby mines have polluted waterways and soil with toxic chemicals. In war, civilians have suffered enormously as abusive armed groups have enriched themselves by exploiting gold and diamonds. Some governments have been directly complicit in child labor and other abuses linked to mining, and have had no trouble selling tainted minerals in global markets.

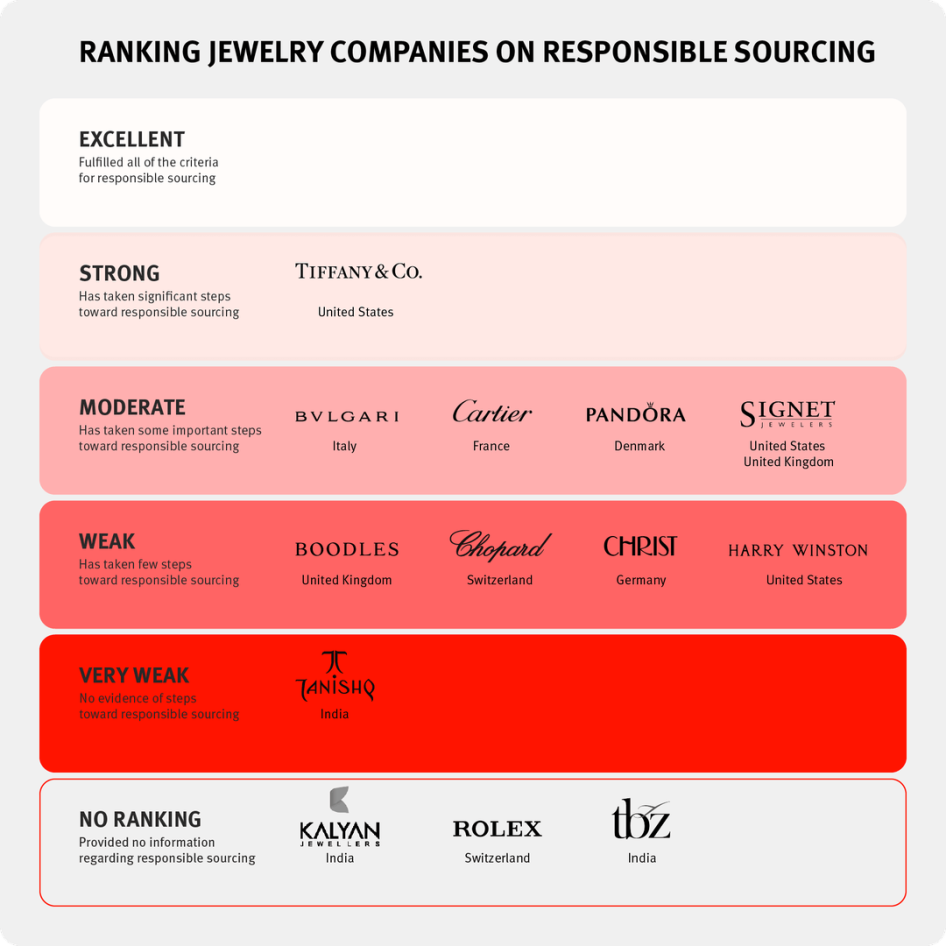

We recently examined 13 well-established jewelry brands for the steps they are taking to prevent human rights abuses throughout their supply chains. We found that most of these companies are unable to trace the origins of their gold and diamonds, cannot adequately assess the full range of human rights risks facing their operations, and are not being transparent enough about their supply chains or even about their own efforts to prevent abuses.

We also found that many companies are over-reliant on the Responsible Jewellery Council, an industry group with over 1,000 members. The RJC has positioned itself as a leader for responsible business in the jewelry industry, but its governance, standards, and certification systems have shortcomings. Despite its limitations, many jewelry companies present RJC certification alone as evidence that their gold and diamonds are “responsibly” sourced.

The good news is that some companies have adopted very good practices that could be replicated by others. Among the companies we examined, Tiffany and Co. stands out for its ability to track its gold back to the mine and its thorough assessments of human rights. In the industry more broadly, some exciting initiatives have emerged in recent years to show that change is possible. A growing number of small jewelers are sourcing their gold from small-scale mines that have been transformed, with the help of nongovernmental groups, into professional operations where rights are respected. I recently met some of them at the “Fair Luxury” conference in the UK: A room packed with young jewelry makers and designers—most of them women—who were sourcing their gold from fair-trade-certified mines, and who were eager to see more gold and precious minerals from such sources on the market.

Consumers also increasingly demand responsible sourcing. Many younger consumers in particular are concerned about the origins of the products they buy, and want to be sure that the jewelry they purchase has been produced under conditions that respect human rights.

So, when you buy a piece of jewellery this Valentine’s Day, ask the jeweller where the piece is from and what steps they have taken to ensure it was produced responsibly. The more customers ask tough questions, the better.