Update: On January 31, Euromaidanpress published an article pointing out that the banned Russian-language version contains a discrepancy in translation: whereas in one sentence in the book, Antony Beevor attributed the killing of Jewish children in Belaya Tserkov to “Ukrainian militias,” the Russian-language version published in Russia that was banned for import for sale in Ukraine, attributes the killings to “Ukrainian nationalists.” Mr. Beevor could certainly demand that the publisher amend this translation. But as the article points out, this does not make the Ukrainian government's decision justified or defensible, and we look forward to seeing the government rescinding it, and an end to its practice of banning books.

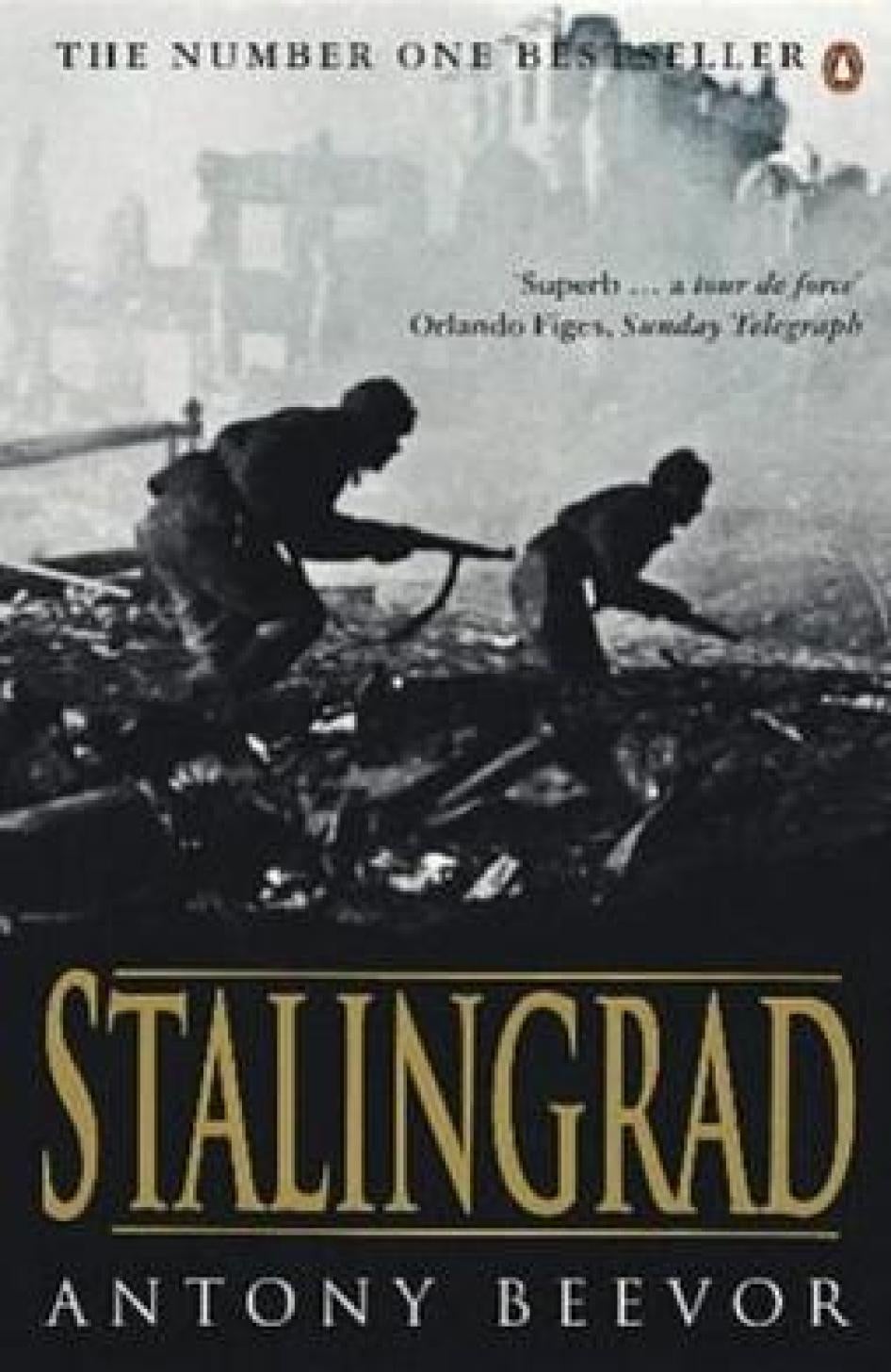

Ukraine recently banned the import of Antony Beevor’s 1998 bestselling history book on the battle of Stalingrad, the latest in a series of misguided steps allegedly to promote “national security” that violate freedom of expression in ridiculous ways.

The government said Beevor’s book fell afoul of a 2016 law banning the import, for commercial purposes, of “propaganda” encroaching on Ukrainian sovereignty and security. The offending passage relates to the August 1941 execution of 90 Jewish orphans in Belaya Tserkov, allegedly carried out by Ukrainian militias. A Ukrainian official with the agency that put Stalingrad on the list of banned books claimed Beevor’s source was, “reports of the Soviet People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs.” Beevor said his source is an anti-Nazi German officer.

Bookshops in Ukraine can import and sell English-language editions of Stalingrad, just not the Russian-language edition published in Russia. Individuals can bring up to 10 copies of the book into Ukraine.

Ukrainian officials have every right to freely debate the facts about the 1941 atrocity, but they don’t have the right to freely ban content. The fact that it’s fine to sell other editions of Stalingrad shows that at times the government’s decisions about banning content have nothing to do with legitimate national security concerns. It also reveals the assertion about Beevor's source as a flimsy excuse.

The real goal is to ban books published in Russia, and it’s embarrassing that authorities are willing to go as far as accuse a well-established historian of bias to justify it. The edition appeared on the ban list on January 10 along with 25 other books, all published in Russia, including a famous Russian author’s history of Russia and a book about Emperor Nicholas II’s affair with a ballerina.

Beevor has called the ban utterly outrageous, and he’s right. It is also, sadly, consistent with other steps the government has taken to restrict free expression, justifying them by the need to counter Russia’s military aggression in eastern Ukraine and anti-Ukraine propaganda.

A May 2017 presidential decree banned major Russian companies and their websites from operating in Ukraine, targeting Russian social media used by millions of Ukrainians daily, language and accounting software, and other online businesses.

In July and August, Ukraine’s security services expelled or denied entry to several foreign journalists – three from Russia and two from Spain – for allegedly engaging in anti-Ukrainian “propaganda.”

Ukraine is fighting a war in its eastern region against Russia-backed armed groups, and Crimea remains occupied by Russia. The government has rights and reasons to protect Ukraine’s security. Arbitrarily banning speech isn’t among them.