When a colleague from Memorial, a leading Russian rights group, called me early in the afternoon of January 9, I cheerfully sang, “Happy New Year!” It was the first working day after Russia’s generous winter holidays, and the day was resplendent with bright sunshine, blue skies and pristine white snow, which dusted the city overnight after weeks of slush and greyness. “I’ve got bad news,” the colleague said. “They’ve taken Oyub.”

Chechen police rounded up 60-year-old Oyub Titiev, the Chechnya director for Memorial. Oyub missed a meeting with a friend and wouldn’t answer his phone, so the friend eventually drove to the village where Oyub lived with his family, some 30 miles from the Chechen capital. On the way, he saw Oyub’s car, apparently being searched by police officials. It was around 10:30 a.m. Oyub waved for him to drive on. A while later, the man went to the local police station and saw Oyub’s car parked in the yard. Fearing for his safety, the friend contacted his colleagues.

Fabricated Marijuana Charges

Memorial immediately sent a lawyer, but the police didn’t let him in saying, they knew nothing of Oyub Titiev. Only close to 5 p.m., after a flurry of news reports and phone calls to officials in Moscow by Memorial’s leadership and others, did officials in Chechnya finally acknowledged Oyub’s detention. Police allowed the lawyer into the station and told him his client would be charged with illegal possession of a large quantity of drugs.

The detention report, which was processed in another three hours, says the police had had found a plastic bag with 180 grams of marijuana in the suspect’s car. On January 11, Oyub was formally indicted and remanded to pretrial custody. On January 16, he gave his lawyer a letter addressed to President Putin stating he was innocent and emphasizing that if he ever admits to being guilty it could only mean he was forced to confess under torture. Police have already threatened Oyub with dire repercussions to his family if he persists in refusing to confess. Also, the day after he was detained, police raided his home looking for his brother and his son. Enraged by the fact neither was in Chechnya, the officers kicked the female family-members out of the house, locked it, and took the key.

I’ve known Oyub for 15 years. He’s a model teetotaler, an observant Muslim, and a fitness fanatic who lifts weights and goes for long runs on mornings when deprived of his beloved gym. The idea of him peddling weed is preposterous and would be raucously funny except that it’s dead serious. Chechen authorities are well-known for successfully fabricating drug cases against critics.

When I traveled in Chechnya for human rights work, Oyub , despite my vehement protests, wouldn’t let me get a taxi and would drive me himself to some remote mountain village where I needed to speak to a victim of abuses. Now Oyub, my colleague, my friend, is behind bars and could be locked up for years.

Chechen authorities are punishing him for daring to conduct human rights work in Chechnya, a nearly totalitarian enclave within Russia, where the local Kremlin-sponsored leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, has been eradicating all forms of dissent through brutal repression.

“I will tell you how we are going to break the spine of our enemies.”

In a December 26 statement, Kadyrov’s right-hand man, Magomed Daudov, said human rights defenders were public enemies who should be "isolated from polite society,” and clearly implied they should be executed. In a January 17 Grozny-TV broadcast, nine days after Oyub’s arrest, Kadyrov raged at human rights defenders: “They have no Motherland, no ethnicity, no religion… They don’t even understand what it means. They have interests. A person [like Oyub Titiev] working for them and this person claiming to be a Chechen … I am very surprised to see such a person. I am very surprised to see his relatives who don’t stop him. They should know that here [in Chechnya] it won’t work… Now, all sorts of [rights defenders] keep coming here … keep smearing our Chechnya, trying to provoke us… Well, I will tell you how we are going to break the spine of our enemies.”

Memorial’s Office Torched

Oyub’s arrest is clearly an attempt to force Memorial, the only human rights organization that still maintains presence in Chechnya and exposes enforced disappearances, extra-judicial killings, and other egregious abuses perpetrated by local authorities with Moscow’s tacit blessing, to leave and shut the door. In recent days, Chechen police raided Memorial’s office in Chechnya, tried to intimidate the staff, and harassed their landlady for housing a subversive organization.

Two senior Memorial staff and a defense attorney from Moscow arrived in Ingushetia, the region adjacent to Chechnya, soon after Oyub’s arrest. They drove from there to Chechnya every morning to work on the case, and then returned at night. They felt safer staying in Ingushetia, especially as they were under heavy surveillance while in Chechnya. Several days into their stay, on January 17, masked arsonists torched Memorial’s Ingushetia office. A coincidence? Hardly. More like a signal: stay away or else. Yet when asked about the arson attack and its apparent connection Chechnya’s leadership cracking down on Memorial, President Putin’s spokesperson said merely that the attack happened “in a different republic” and that the drug case was being dealt with by the investigation authorities.

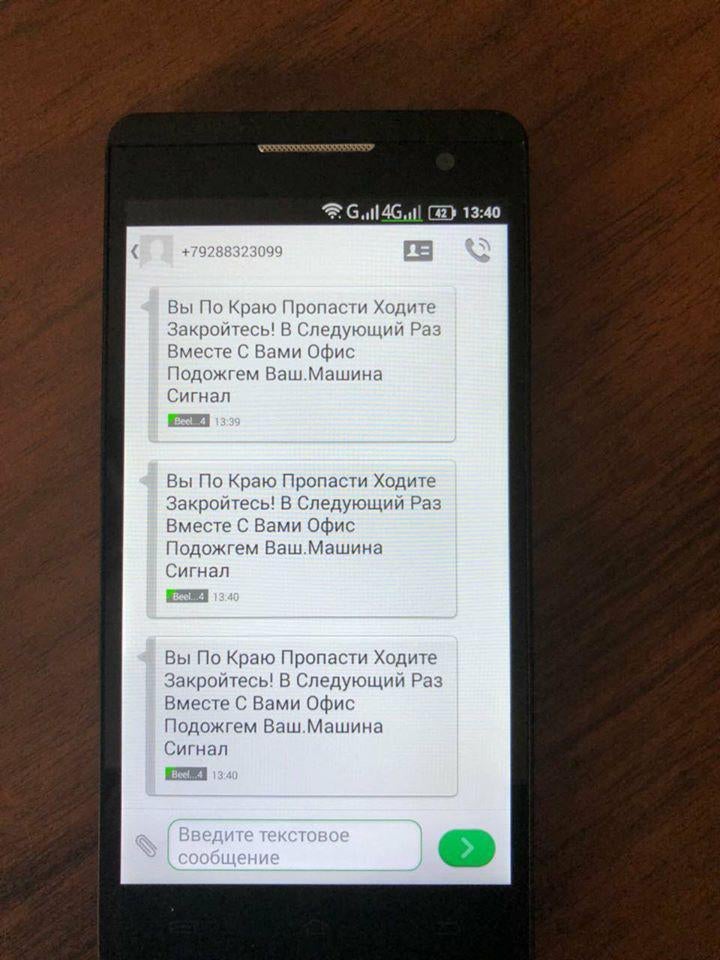

Yet five days later, someone torched the car of one of Memorial’s drivers. Hours later, someone sent text messages to Memorial’s mobile phone saying, “You’re walking on the edge of the abyss. Shut down! Next time we’ll burn your office, with you inside. The car is just a warning.”

A Legacy of Courage

Eight and a half years ago, I was walking along a boulevard in central Moscow when another colleague from Memorial called. I answered the phone, squinting at the sun. “I have bad news,” he said. “Natasha has disappeared.” Natalia Estemirova, a wonderful colleague and a close personal friend, was the embodiment of Memorial in Chechnya. It was July 15, 2009, and that morning a witness saw security officials force her into a car in Grozny. The next few hours were a blur of phone calls to literally everyone who is anyone. We thought we could still save Natasha.

We were wrong. Her body with gunshot wounds was already lying in a wooded area, also in neighboring Ingushetia, waiting to be found later that day. After Natasha’s murder, Memorial suspended its work in Chechnya for a few months, but Oyub Titiev, whom Natasha had brought to Memorial back in 2000, when the second Chechen war was raging, insisted they re-open, arguing that the only way to honor Natasha’s memory was to continue her work against all odds.

We could not save Natasha but we can still save Oyub and we can save Memorial. All it takes is for Russia’s president to pick up the phone and tell his protégé in Grozny to leave the man and the organization alone.

Surely, we can make that happen, can’t we?