Dear Mr. Brody, I am reaching out to you today as I would like to know what are the options for the victims of [Yahya] Jammeh now that he is no longer president of The Gambia? We just had confirmation today of my father's death, a fierce critic of his regime, after searching for the truth for years. … As the person who has provided the necessary linkages that enabled the Hissène Habré case to move forward, I was wondering if we could speak? Nana-Jo Ndow (February 5, 2017).

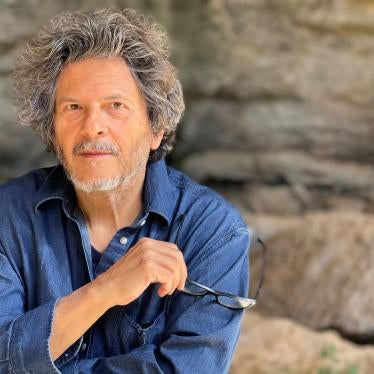

I have received many emails like this one from around the world since the 2016 conviction in Senegal of Hissène Habré, the former dictator of Chad, for crimes against humanity. During the 18 years working on the Habré case, I had also heard a lot about Yahya Jammeh’s repressive regime in next-door Gambia. So, with the Habré case behind me, I decided to meet Nana-Jo in New York. If Jammeh was to be brought to justice, it would be because people like her spoke out.

Jammeh, who ruled Gambia for 22 years, has been implicated in the arbitrary arrests, torture, and enforced disappearances that were the hallmark of his government. He went into exile in Equatorial Guinea in January after being defeated in elections in December 2016.

In April, I traveled with a group of Habré’s victims to Gambia to share their experiences with the new association of Jammeh’s victims. The Gambians were inspired by how the Chadians had overcome so many obstacles. Fatoumatta Sandeng, daughter of Gambian opposition leader Solo Sandeng whose murder in custody in April 2016 galvanized opposition to Jammeh, took away the lesson that victims’ voices mattered. Baba Hydara, son of newspaper editor Deyda Hydara, who was murdered in 2004, said that the Chadians explained that it was a “long, long, long battle, but we are ready. ”

The Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa and Human Rights Watch were tasked with convening a larger group to develop a plan of action, with the financial support of the Fondation pour l'égalité des chances en Afrique, whose president, Mohamed Bouamatou, from Mauritania, said, “We want to send the message that no African leader suspected of crimes against his people should think that he is above the law or out of reach of his victims.”

After months of preparation, we held that convening last week in Banjul, Gambia’s capital. Nana-Jo came from New York. Tutu Alicante, head of EG Justice, which campaigns on Equatorial Guinea, was also there, as was TRIAL International, which was instrumental in the arrest in Switzerland against Jammeh’s interior minister, Ousman Sonko, charged for crimes against humanity. The victims and other participants unanimously decided to launch the “Campaign to Bring Yahya Jammeh and his Accomplices to Justice” (#Jammeh2Justice).

At a packed press conference, Fatoumatta Sandeng read out the campaign’s declaration: “We are committed to attain our ultimate goal, which is to ensure that Yahya Jammeh, as well as those who bear the greatest responsibility in the crimes of his government, are brought to trial with all due process guarantees.” Other victims spoke, including Amadou Scattred Janneh, who was sentenced to life imprisonment under Jammeh for making T-shirts with the slogan “End Dictatorship Now,” and Imam Baba Leigh, a Muslim cleric who was savagely tortured and detained incommunicado for five months.

Fighting back tears, Nana-Jo described how her father, Saul Ndow, a Gambian-Ghanaian dissident businessman whom Jammeh suspected of plotting, disappeared from Senegal in 2013 and is presumed to have been brought to Gambia and killed. “We, his family have been going through immeasurable pain for the past four and half years and today I stand here because we want answers and we want justice and we shall not give up until those responsible are held accountable.”