According to the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack — which includes United Nations agencies and non-governmental organizations such as Human Rights Watch — there has been a pattern of attacks on students, teachers or schools in at least 27 countries around the world since 2013. State security forces and non-state armed groups have targeted students, teachers, academics, teachers’ unions and education institutions for political, military, ideological, sectarian, ethnic or religious reasons.

These attacks have included killings, enforced disappearances, abductions, forced exile, imprisonment, torture, maiming, placing landmines around schools, destroying educational buildings and materials, sexual violence, and recruitment and use of child soldiers, as well as the military use of schools. During armed conflict, government or opposition forces use schools and universities as bases, barracks, observation posts, storage for weapons, detention and interrogation centres, or for military training and to recruit children into their forces. Schools are used by warring parties in the majority of conflicts around the world today. When troops and weapons are present in schools, it can provoke attack by opposing forces, placing both students and educators at risk of injury — or even death.

At Human Rights Watch, we see frequent reports of students and schools coming under attack in war zones. Describing how an armed group occupied a primary school in their town in the Central African Republic from late 2014 until October 2016, a school official told us: “They destroyed desks and chairs. We were able to get them to vacate one of the buildings so we could restart the school, but they still occupied half of the school and ruined the building. They used our school grounds as their toilet. They used the desks for firewood.” In addition to the Central African Republic, Human Rights Watch has documented attacks on schools in Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palestine, the Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Ukraine and Yemen.

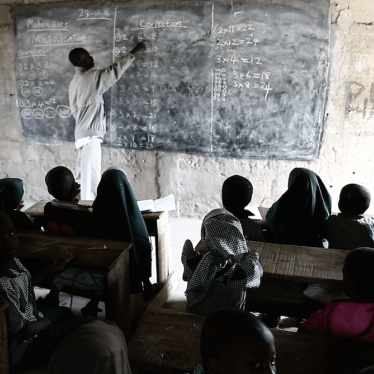

Worldwide, 250 million children live in areas affected by armed conflict; one in four of these children is not in school. Military use of schools can also disrupt children’s education and cause destruction of school infrastructure. In an environment of violence and fear, school attendance and education quality can decline, and schools might even shut down. Girls are disproportionally affected because they are especially vulnerable to sexual violence on school grounds, or are kept home by their parents when the security situation deteriorates.

Schools should be safe spaces for children, even amid armed conflict. Safe schools not only provide children with an education, but also offer much-needed stability and routine during times of conflict, help ease the impact of war on children’s mental health, and provide a place to play and be a child despite the discord all around. Schools can provide children with access to health information, help them learn how to avoid landmines, and allow them to gain the knowledge and skills to build a brighter future for their countries. Keeping schools open is also advantageous to society at large, because diminished education levels affect a country’s economic, political and social development. For example, studies have linked education to reduced poverty and better maternal and child health.

Interrupted or abandoned education shouldn’t be considered just another devastating by-product of war. The Safe Schools Declaration, an intergovernmental political commitment developed by countries in early 2015, is making students safer around the world. By joining the declaration, countries make a commitment to take concrete steps to make it less likely that students, teachers, schools and universities are the target of attacks, and to lessen the negative consequences in case schools are attacked.

These common-sense measures include: collecting reliable data on attacks and military use of schools and universities as well as the victims of attacks; providing non- discriminatory assistance to victims of attacks; investigating and prosecuting allegations of violations of national and international law; supporting the continuation of education during armed conflict; and bringing a set of specific guidelines to protect schools and universities from military use into domestic policy, doctrine and military manuals. Governments also agree to develop and adopt ‘conflict sensitive’ education policies and programmes that promote social cohesion among groups, rather than increase existing tensions, and meet regularly with civil society and relevant international organizations to review the implementation of the declaration. So far, 68 countries — many of them affected by conflict — have joined the declaration, demonstrating a growing international commitment to safeguard education during war.

Endorsing the Safe Schools Declaration is an encouraging step in the right direction, but countries should also implement these declaration commitments to ensure that schools are protected, so that all children everywhere have the chance to reach their full potential. Continuing education in conflict settings is indispensable for ensuring children’s fundamental right to a safe education. Wartime is no exception.