What kind of cases have been brought to trial so far?

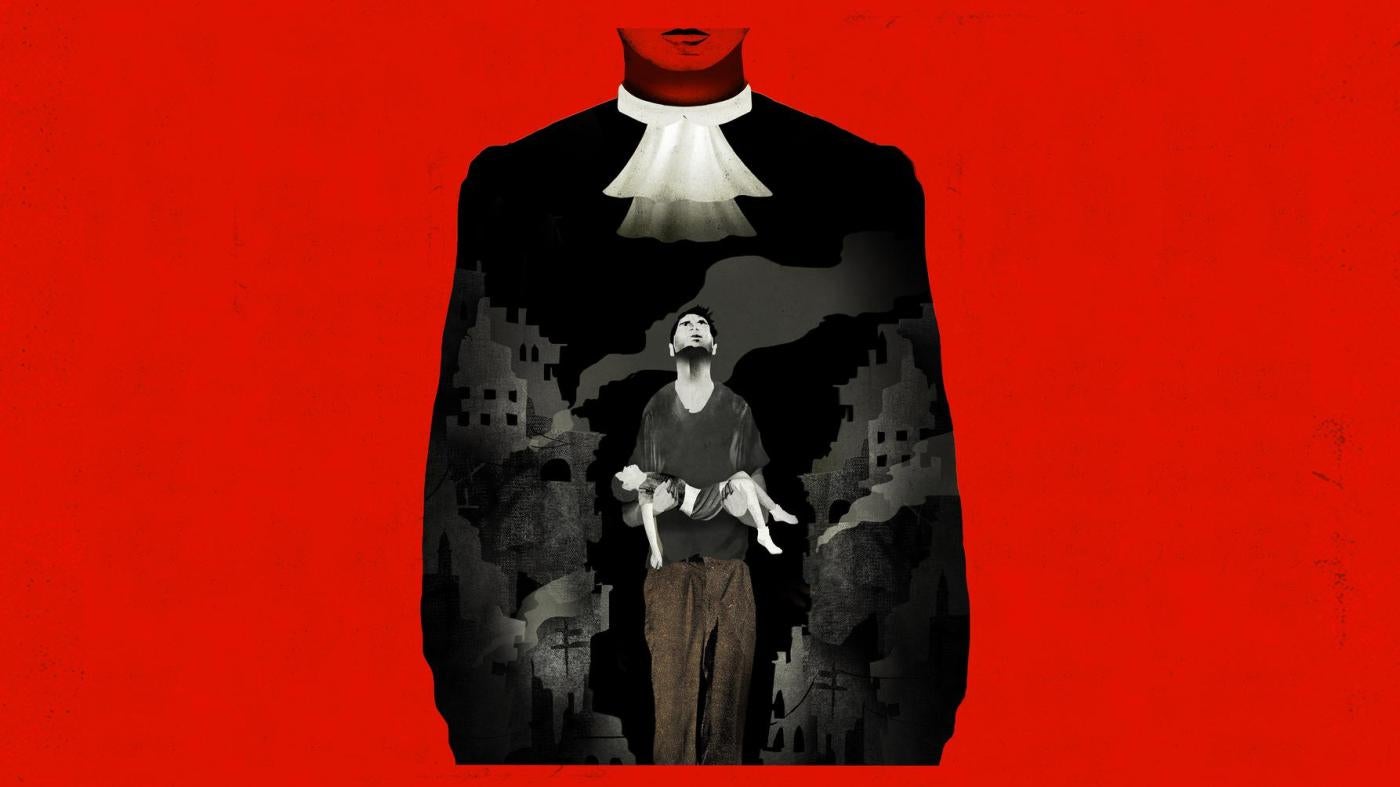

To date, seven cases for war crimes in Syria were brought to trial, three in Sweden and four in Germany. These few cases have mostly been against members of the Islamic State [ISIS], Jabhat al-Nusra – an affiliate of Al-Qaeda, and rebel groups. Only one has addressed crimes committed by a member of the Syrian army.

In Sweden and Germany, you can only bring to trial people who are present in your territory. So only low-level people who happen to be present in those countries have been brought to trial so far. The high-level people are still in Syria. But you can preserve and collect evidence for future prosecutions. Also, these countries can potentially issue arrest warrants for alleged perpetrators still in Syria.

These prosecutions are important to send the message that Europe is not a safe haven for war criminals, that if you commit those crimes and come to Europe you will be brought to justice, and that even in the Syrian conflict there are repercussions for these crimes. Syrian refugees can play a key role in helping authorities in Europe build cases against people who are identified as having committed crimes back in Syria.

Justice for Syria is a very long-term project. These cases in Europe are just the first small steps, and we want to see more of them.

What kind of evidence has been used in the current trials?

Many of these cases stemmed from photos and videos depicting the crimes. As far as we know, none of these cases happened because of evidence gathered by victims, although we hope to see more of that as authorities improve their engagement with Syrian refugees. Information provided by Syrian activists has been crucial in at least one of these cases.

Have arrest warrants been issued for people currently in Syria?

Not yet. In Germany, there are two claims that have been brought by victims and nongovernmental organizations against high-level Syrian officials. The federal prosecutors are deciding whether to open an investigation, and if there’s enough evidence, they can issue an arrest warrant for these people in Syria. They can’t be prosecuted until they set foot in Germany, but it does send them a message – if you commit war crimes and come to Germany, you will face justice.

Who did you speak to for this report?

We interviewed 45 Syrian refugees in Sweden and Germany. Twenty-two told us they’d been detained in Syrian government facilities and 16 told us they had been tortured while in detention.

Some told us they witnessed widespread torture and killings. Some were also wounded in attacks on their cities.

Why are we asking for justice as opposed to more immediate needs, like better shelter or healthcare?

It’s not a one-or-another question. First, because we believe in human rights and rule of law, there is an obligation to hold those who commit horrible crimes and violate our core values accountable for their actions. Second, lasting peace does not happen without a measure of justice and accountability that address the underlying causes of the conflict. Then there’s the more personal need for justice for these victims. When I asked the Syrians I interviewed why justice was important for them, they gave me very compelling answers.

What did they say?

One of our interviewees was a woman in her 20s from Raqqa, who was held by ISIS fighters. She said she saw Syrian government soldiers fire 14 bullets into her brother and kill him. She also said she watched five children have their heads cut off. “I couldn’t sleep for a week,” she said. When I asked her about justice, she said, “It’s very important to have justice, which will let me feel that I’m human.”

I also spoke with a man who, while detained in Syria, made a pact with his fellow inmates that the first one to get out would bring their names out, letting their families know what happened to them. They wrote their names on this piece of cloth, and for ink they used blood from their gums – they were so malnourished their gums were bleeding – mixed with rust from the prison. He was the first one to get out and smuggled out the list. He told me, “Having these trials will bring justice to the victims and will deter people [from committing these crimes]. It will send the message that in the end we will hold you responsible.”

What do you want to see happen in Europe when it comes to these cases?

The officials pursuing these cases are doing a great job, considering the challenges. Just to give you an example, in Germany, investigators are swamped with information they get from different sources, including immigration authorities and the general public. As of this summer, they had received more than 4,000 tips, which they analyze to find relevant information for their investigations. Swedish and German investigators and prosecutors need more manpower and money to do their work effectively.

We also found that both Sweden and Germany are having difficulties reaching out to Syrian refugees and asylum seekers. It’s partly because Syrians don’t trust police and government authorities – they’re afraid, they fled horrible crimes and still have families in Syria, and they don’t want to talk openly. And most of them don’t know these cases are even possible. We would like to see better outreach from authorities towards these communities. It allows people to know what’s happening and how to actively participate in working towards justice.

Why is this important now, with the war still ongoing?

Crimes are still being committed on a daily basis, and we need to tell people that this is not okay. They will face the consequences of what they’re doing. One Syrian activist told me about members of the Syrian government, “These people think that the political solution will come and they will be able to escape to Europe. I want them to feel haunted like they’ve haunted people all their life.”

What struck you about your research?

The resilience and strength of people. These people have suffered horrible crimes, they lost everything, yet they still keep going and fighting for justice.

One of the refugees I interviewed was detained when he was 16; he was a child. He was in jail for three years, where he was tortured. He’s this young man now, living in Sweden, who’s very open about his experience. He’s now fluent in Swedish and the week I was there he had organized a talk in a public library to discuss his experience. He looks like your regular 20-something guy, someone who should have regular problems, like with university and love and family. Then he starts telling you about what happened to him and he does it with a smile on his face and you’re completely blown away by how resilient and how strong this person is.

Talking with people like him cemented in me the conviction that we can’t let people who commit these crimes be free. They shouldn’t be able to comfortably live cushy lives in some other country once the conflict is over. Imprisoning criminals deters others from following in their footsteps, and gives victims an important sense of justice.

This interview has been edited and condensed.