‘Lilly,’ a transgender woman from Uzbekistan, traveled to northern Russia in 2015, in search of work, hoping to earn money for her transition. In December 2016, three men attacked her on the street, forced her into a car, and gang-raped her. They also filmed the rape and extorted money from Lilly by threatening to publish the video online.

Police promptly arrested two of the perpetrators hours later. In May of this year, a court in Murmansk found the two men guilty of extortion with the use of violence and sentenced them to four years in prison. They were never charged with the rape – the rape that changed Lilly’s life irretrievably. “I only wish I could exchange my life for another,” Lilly told me. But the court did recognize that the men targeted Lilly because of “hate” – hatred for her gender identity – a rare breakthrough in Russia.

It’s significant that hostility towards LGBT people was acknowledged as a motivating factor precisely because hate crimes are a serious issue in Russia, and something that the United Nations experts who monitor Russia’s compliance with the International Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) will examine in Geneva this week. It is a difficult task because Russian authorities don’t compile hate crime data and have not been contributing to the OSCE’s statistics on hate crimes, published annually by the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR). Nevertheless, independent monitors flag that the most frequent victims of hate attacks in Russia are non-Slavs, religious minorities, and LGBT people.

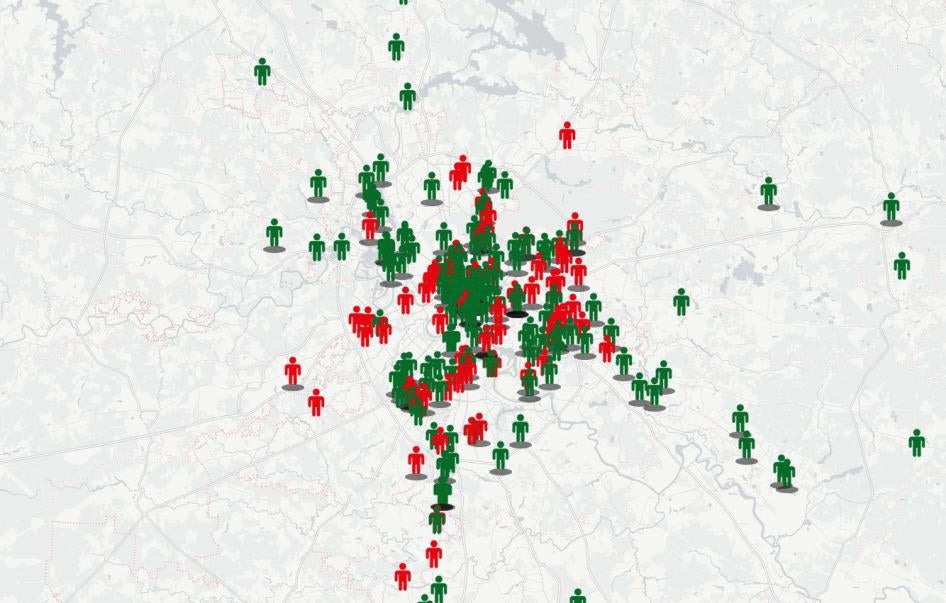

In Moscow, Anastasia Denisova, of Russia’s leading migrant support group Civic Assistance Committee, runs the project “hatecrimes.ru,” which provides legal assistance to victims and, in the absence of official statistics, maps out hate crimes on an interactive map of Russia with the use of countrywide findings by SOVA-Center, an independent think tank. She told me that, “in most cases when non-ethnic Russians are attacked, police begin by treating the victim as the guilty party and our lawyers have to work hard to make them realize who is the victim and who is the aggressor. Also, if a victim of a hate crime was also robbed, for instance, the authorities tend to launch a case on robbery, ignoring the hate motive.”

Russia should ensure that authorities systematically recognize hate motives in a crime as an aggravating circumstance and launch mandatory training programs for law enforcement officials and judiciary. The government should also list hate crimes as a separate category in criminal statistics to give the public a clear picture of the issue’s scope and resume its reporting on hate crimes to the OSCE as part of contributing to international efforts aimed at resolving the problem.