I knew visiting Dhaka in monsoon season was a bit of a gamble, a worry confirmed when I joined thousands of other Bangladeshis stuck in flooded streets for hours on end. But what the rains have brought to the Chittagong Hill Tracts is more than just a spoiled day of sightseeing. The deaths of more than 160 people there last month is a human-made disaster, and a harbinger of worse to come.

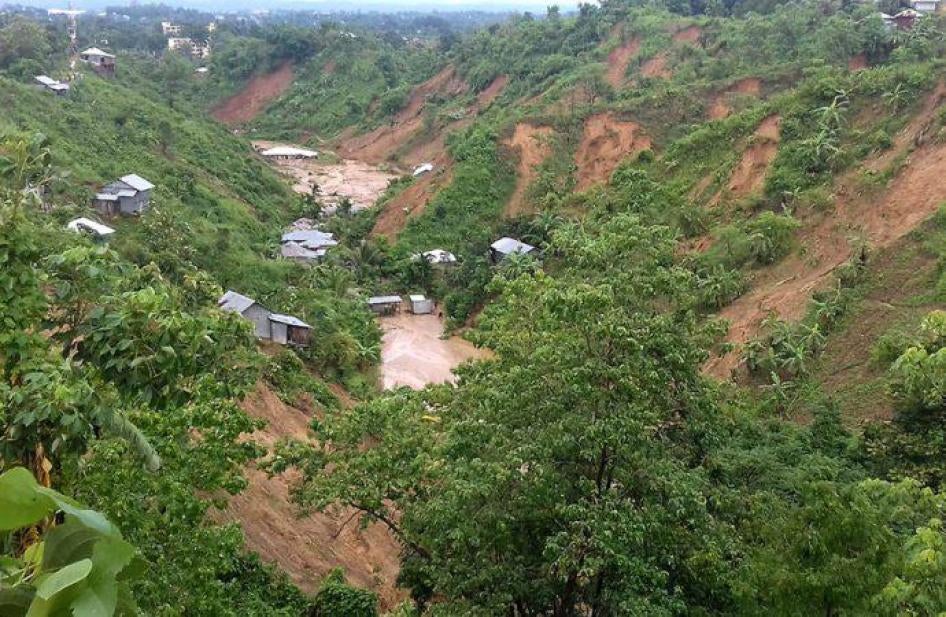

After torrential monsoon rains triggered landslides in the Hill Tracts in south-eastern Bangladesh in mid-June, environmental activists blamed decades of unregulated settlement, development and land-grabbing in Bandarban, Khagrachari and Rangamati districts.

The resulting widespread deforestation has left the area vulnerable to catastrophe. With landslides and other ecological disasters on the rise, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government needs to act to curb corruption and prevent further catastrophes.

In June, hundreds of homes were crushed or buried by mud and rubble in the landslides, the worst to hit the region in Bangladesh’s history. Thousands had to be housed in emergency shelters, while others were cut off for days because roads were blocked or flooded, leaving communities in remote areas of Bandarban, Chittagong and Rangamati districts without water, electricity, and food supplies. Relief efforts were still underway more than ten days after the initial landslides.

Adding to the tragedy, local residents in some areas alleged discrimination in the distribution of relief supplies, with rice meant for victims going to those with powerful political connections.

This is not the first disaster of this kind to strike the Hill Tracts region. In 2007, landslides and hill collapse following heavy rains left more than 120 dead. Scientists anticipate that climate change may now cause greater variability and heavier downpours, with Bangladesh being among countries most vulnerable to the impact.

But what has happened to make the Hill Tracts so disaster-prone is also the extent of forest degradation, accelerated by privatization of the land for agribusinesses like rubber and tobacco, displacement of the indigenous population and the haphazard settlement by Bengali outsiders—policies supported by successive governments since the 1960s. The resulting widespread loss of tree cover has left the area vulnerable to erosive forces.

What is shocking is that all of this is well known, and this latest Hill Tract disaster entirely predictable—and preventable. A study by the Disaster Management Centre of the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) on the 2007 disaster described “[u]nsustainable lands use and alteration in the hills including indiscriminate deforestation and hill cutting” as factors that aggravated landslide vulnerability in the region. The study called for enforcement of existing laws, and adopting stronger measures to protect the Hill Tracts forests in order to avert further catastrophes.

None of that was done. Instead, government ministries have pointed fingers anywhere but at themselves for the failure to prevent deforestation. Although clearing forest cover without government approval is banned under the Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act, Bangladeshi authorities rarely take action against those engaged in illegal logging, forest conversion into commercial crop plantations or construction.

But it is impossible to understand the disaster in the Hill Tracts without acknowledging the long-standing conflict that has wracked the region for half a century.

Resentment over discrimination and forced displacement during the construction of a major dam on the Kaptal river in 1962 sparked armed resistance within local communities. Successive governments tried to stem the rebellion by settling the region with ethnic Bengalis, thus reducing indigenous communities to a minority. Security forces resorted to extrajudicial killings, rape, and torture to crush resistance to state policies.

Clashes continued through the 1990s until the signing of a peace accord in 1997 offered hope that indigenous groups would regain their rights. But officials have consistently failed to honor the accord and address long-standing human right violations, which have also included forced evictions and destruction of property. In the most recent example, on June 2, 100 homes in the Longadu upazilla (subdistrict) were burned by Bengali settlers, reportedly while army and police stood by. Bengali settlers now outnumber indigenous people, many of whom have been displaced and their lands used for tobacco cultivation, fruit plantations or timber cutting.

Restrictions prevent most foreigners from visiting the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and the overwhelming military presence means reporting is closely monitored.

But with landslides and other ecological disasters on the rise, Sheikh Hasina’s government can’t wish away the evidence of the high human cost of corruption and environmental abuse.