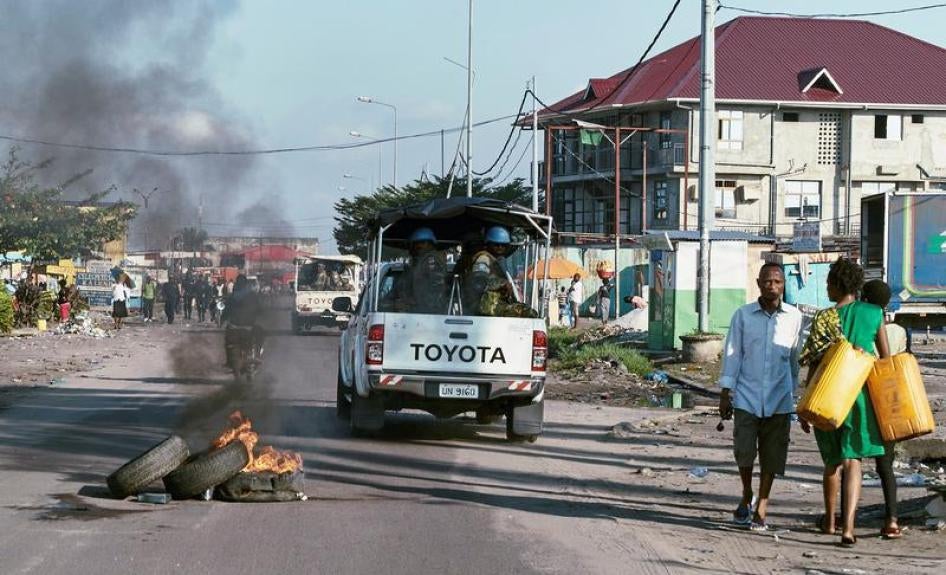

Congo is facing a political and economic crisis, and it’s only growing worse. President Joseph Kabila was due to step down in December 2016, at the end of his constitutionally mandated two-term limit. But he has managed to hold on to power by delaying elections and overseeing a brutal crackdown against those calling for the constitution to be respected.

A deal mediated by the Catholic Church, signed on Dec. 31, included clear commitments to hold elections by the end of 2017 and specified that Kabila would not be a candidate or try to amend the constitution. Additionally, the main opposition coalition would lead the transitional government and a national oversight council, and measures would be taken to open political space. These commitments have largely been ignored, and the prospect of credible elections by year’s end seems increasingly unlikely.

The country’s influential conference of Catholic bishops warned this month that the country is in a “very bad” state and called on all Congolese to “stand up” and “take [their] destiny into [their] own hands.” This followed an “urgent appeal” from former United Nations secretary general Kofi Annan and nine former African presidents, who warned that the future of the country is in “grave danger.”

As repression against the political opposition, activists, journalists and peaceful protesters continues, violence by dozens of armed groups and government security forces has intensified across much of Congo — which is the size of Western Europe and shares borders with nine other countries. The country is also facing a deepening economic crisis, which has contributed to massive youth unemployment. During a series of apparently well-planned prison breaks in recent weeks, more than 5,000 prisoners have escaped, fueling insecurity and setting justice efforts back years.

Some of the worst violence has been in the central Kasai region, which until recently had been largely peaceful. Large-scale violence broke out there last August, when government security forces shot dead a local customary chief whose loyalty was in question. This triggered the spiral of violence that has now spread across five provinces and has displaced more than 1.3 million people. At least 3,300 people have been killed, according to the Catholic Church. More than 600 schools have been attacked or destroyed, and an estimated 1.5 million children are affected by the violence.

Government security forces have responded with excessive force, summarily executing suspected members or sympathizers with a militia formed initially to respond to the execution of the local chief. In some cases, soldiers went door to door, killing anyone inside. In the past two months, a government-backed militia, known as the Bana Mura, has destroyed entire villages and “shot dead, hacked or burned to death, and mutilated” hundreds of villagers, including pregnant women, babies and small children, according to the United Nations.

At least 42 mass graves have been identified in the region, most believed to be the work of government security forces.

It was during their investigation of these widespread human rights abuses in March that two members of the U.N. Group of Experts on Congo — Michael Sharp, an American, and Zaida Catalán, a Swede – were executed and buried in a shallow grave. The government has provided no credible information on responsibility for the murders. The four Congolese who had accompanied them — their interpreter, Betu Tshintela, and three motorbike drivers — are still missing.

This month, the U.N. Human Rights Council authorized an international investigation into the violence in the Kasai region. The resolution, adopted after weeks of intense negotiations, doesn’t go as far as the situation warrants. But it does bring hope of uncovering the truth of the horrific crimes and identifying those responsible. And it’s a step toward justice. Yet recent statements by several senior Congolese officials — contending that the international role will be limited to technical support for a Congolese investigation — raise doubts.

The United States and the European Union have taken strong positions in pressing for justice for the murders of the U.N. experts and the thousands of Congolese victims and recently imposed new targeted sanctions against top Congolese officials. The U.S. sanctions showed that Kabila does not have the unconditional support from the Trump administration that many Congolese officials were hoping for.

But more could be done. The United States and E.U. could go further up the chain of command and also sanction those who have helped to finance Kabila and his government’s campaign of repression and abuse. Congo’s neighbors and other regional players — including Angola, whose government appears increasingly concerned about Kabila’s inability to resolve the crises facing the country — could also take a stronger stance in pressing Kabila to allow for a peaceful, democratic transition before year’s end.

There is still time to heed the dire warnings of the Catholic bishops and former African leaders and stop the escalation of violence, abuses and instability that threaten both Congo and the entire region. But this requires high-level engagement and sustained, targeted and well-coordinated pressure on Kabila and his government at the national, regional and international levels. Time is of the essence, with the situation on the ground spiraling out of control and the deadline for elections at year’s end fast approaching.