(Beirut) – Egyptian internal security forces waging a campaign in the Sinai Peninsula against an affiliate of the Islamic State may have extrajudicially executed at least four and perhaps as many as 10 men in January 2017, Human Rights Watch said today. The security forces may have arbitrarily detained and forcibly disappeared the men and then staged a counterterrorism raid to cover up the killings.

A Human Rights Watch investigation relying on multiple sources of evidence including documents, interviews with relatives, and an edited video of the purported raid made public by the authorities suggests that police arrested at least some of the men months before the alleged gunfight at a house in North Sinai and that the raid itself was staged.

“These apparent extrajudicial killings reveal total impunity for Egypt’s security forces in the Sinai Peninsula under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s counterterrorism policies,” said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Prosecutors need to conduct a full and transparent investigation to get to the bottom of what appear to be grave abuses.”

The killings appear to fit a pattern of abuses against civilians by both military and internal security forces who are fighting the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) under the largest deployment of Egyptian troops in Sinai since Egypt’s 1973 war with Israel. Fighting in North Sinai has left hundreds dead since 2013, including civilians, security force members, and alleged ISIS fighters. The ISIS affiliate, which calls itself Sinai Province, has killed scores of civilians, targeting many either for alleged collaboration with the authorities or because they were Christians.

Journalists and human rights groups are rarely able to investigate frequent and credible reports of abuse because the government denies them access to North Sinai.

These apparent extrajudicial killings reveal total impunity for Egypt’s security forces in the Sinai Peninsula under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s counterterrorism policies,” said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Prosecutors need to conduct a full and transparent investigation to get to the bottom of what appear to be grave abuses.

Deputy Middle East and North Africa Director, Human Rights Watch

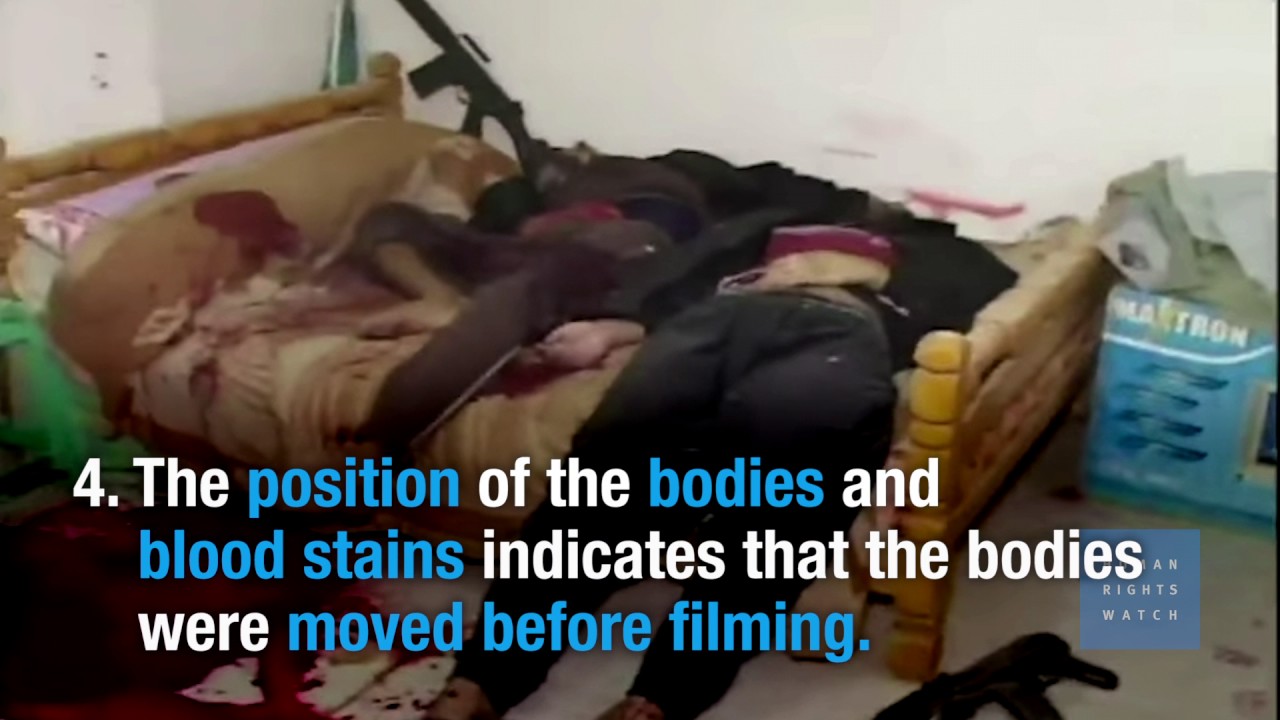

That same day, the ministry also released a short video purporting to show the raid itself. The video was posted on YouTube with the title, The death of 10 terrorist elements in an exchange of fire with security forces in North Sinai. The heavily edited clip shows at least eight commandos approaching a building, two of them firing at a man on the ground outside, and six dead men in civilian clothes lying in various rooms inside the building, surrounded by weapons, fresh pools of blood, and walls with bullet holes.

Human Rights Watch spoke with relatives of three of the dead men – Ahmed Rashid, Mansour Gam’a, and Mohamed Ayoub – and a lawyer who is representing the families of Rashid and a fourth man, Abd al-Aty Abd al-Aty. All said that the Interior Ministry’s security forces had arrested the men without warrants in October and November 2016, months before the alleged January raid took place.

Salah Salam, a member of the government-sponsored National Council for Human Rights, told the Aswat Masriya news service on January 15 that the names of the six slain men had been on a list of 650 people allegedly being held without charge in North Sinai, which local residents had earlier asked him to deliver to a presidential pardon committee. Salam told Human Rights Watch on March 16 that he did not have a copy of the list that he sent to the pardon committee, but that those who compiled it told him that the names of the six men were included, and that the government must investigate

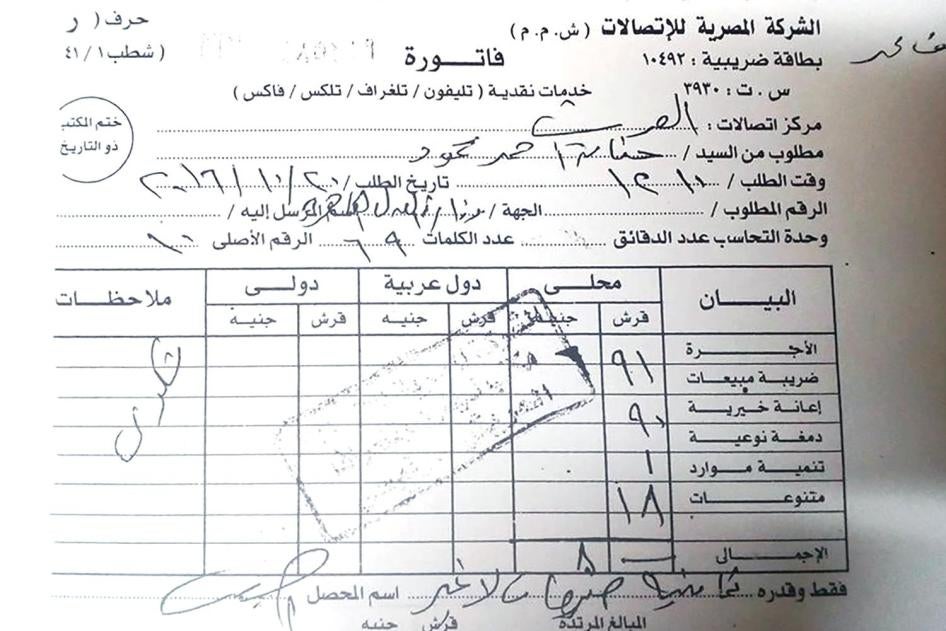

The families of Rashid and Abd al-Aty sent telegrams to the authorities inquiring about the two men shortly after their arrests and gave Human Rights Watch photos of receipts showing the dates they had sent the telegrams in October and November. The telegram receipts seen by Human Rights Watch contain serial numbers that could verify to investigators when they were sent. The two families also filed a joint complaint to the prosecutor general asking him to investigate their relatives’ deaths. The authorities did not respond to any of these complaints or requests for information.

Neither the Interior Ministry nor the public prosecution office have opened an investigation into the deaths, the relatives and lawyer told Human Rights Watch. The Interior Ministry’s statement claimed that security forces had conducted the raid after receiving permission from prosecutors.

“In addition to a prompt and thorough investigation, the Egyptian government should open North Sinai to journalists, human rights investigators, and aid groups,” Stork said. “For years now, North Sinai has been a black hole.”

Doubts Cast on Government Account

Independent observers are rarely allowed to investigate the ongoing conflict in North Sinai, which the government treats as a closed military zone and where curfew hours and a state of emergency have been in place since October 2014. Egyptian journalists who have reported from North Sinai have faced prosecution, as have analysts who have written about the conflict. Ismail al-Iskandrani, a researcher who reported on Islamist movements and developments in the Sinai Peninsula, has been detained pending trial since November 29, 2015, on charges of spreading false news and aiding an illegal group.

Human Rights Watch reviewed the Interior Ministry’s video and other documents provided by the families, including burial forms and photographs of three of the men’s bodies taken at a morgue. Human Rights Watch also consulted with a forensic expert and several military experts regarding the photos and the video of the raid.

Two military experts consulted by Human Rights Watch said that certain elements of the video led them to doubt its authenticity, including a bright floodlight that illuminated the commandos as they approached the house and the commandos’ behavior during the raid, which did not indicate that they felt under threat.

Stefan Schmitt, the director of the international forensic program at Physicians for Human Rights, told Human Rights Watch that the video was too heavily edited to be taken as a credible depiction of the authorities’ story and that the positioning of the bodies and blood inside the house raised the suspicion that at least one of the bodies had been moved prior to the video taping. Sutures on at least two of the bodies photographed in the morgue indicated that autopsies were performed and that there should be autopsy reports, he said. Ayoub, the lawyer representing the families of Rashid and Abd al-Aty, told Human Rights Watch that the authorities have not provided the families with such reports.

Ayoub and the relatives of Rashid told Human Rights Watch that they had viewed the bodies of Rashid and Abd al-Aty in the morgue and that both appeared to have been shot once in the head. Both they and a relative of Gam’a also described reddened areas on the feet and hands of three of the bodies that they believed were signs of the use of electric shocks and cigarette burns, but Human Rights Watch could not independently confirm the cause of these marks or the existence of bullet wounds.

The relatives all said that they had learned of the men’s killings from the news and that the authorities had not contacted them. A local political activist who is coordinating the Arish “popular committee” said that the only response from the authorities had been to release about three dozen illegally detained people in North Sinai.

Human Rights Watch sent letters by email to the Interior Ministry and prosecutor general on March 6, inquiring about the families’ claims and whether the authorities had opened any investigation. Neither has responded.

Analysis of Statement and Video of Interior Ministry

The roughly one-and-a-half-minute video posted on YouTube by the Interior Ministry on the day of the alleged raid repeated a statement released the same day on the ministry’s Facebook page. The statement identified a man named Ahmed Mahmoud Yousef Abd al-Qader as an alleged commander with the local ISIS affiliate whom the ministry blamed for organizing “terrorist groups” and instructing them to carry out a string of attacks, including a coordinated assault on two police checkpoints in al-Arish just four days earlier that left eight police officers and one civilian dead.

After “intensive follow-up field operations,” the ministry statement said, its forces were able to identify some of the alleged ISIS fighters involved in the January checkpoint attacks. The ministry claimed that the attackers had been moving frequently between various hiding places, but relatives of Ayoub, Gam’a, and Rashid told Human Rights Watch that police had arrested the three men at their homes. Far from living as fugitives, they said, Rashid had married two months before his arrest and Gam’a lived with his wife and frequently visited a doctor with her to seek treatment for infertility.

The ministry said that counterterrorism forces tracked the men to an abandoned “chalet” near al-Arish’s Fourth Police Department. On January 13, the counterterrorism forces began their raid on the building, but fighters inside “fired a hail of bullets toward them, trying to escape,” the statement said. The commandos “dealt with the sources of fire,” killing all 10 men inside the building. The statement did not mention any casualties among the counterterrorism forces.

On that day, Rashid’s relative said, dozens of men wearing uniforms with “police” written on them and other men in civilian clothes raided their home in the Samran neighborhood of al-Arish and arrested Rashid without showing a warrant. The authorities had not previously wanted Rashid for any crime, and the relative said they did not know why police came for him.

“It was October 17 around noon,” she said. “Suddenly the door slammed, and I felt terrified when I saw the [security] forces and couldn’t talk.”

Rashid’s relative said that the security forces split up and entered an apartment on the ground floor and Rashid’s on the second floor. They took Rashid into an armored vehicle for a moment and then returned with him.

“I asked [an officer] what was going on but he didn’t answer,” his relative said. “I had to go out but I was hearing voices. They hit him while his grandmother was standing there. She yelled at them: ‘Shame, shame!’”

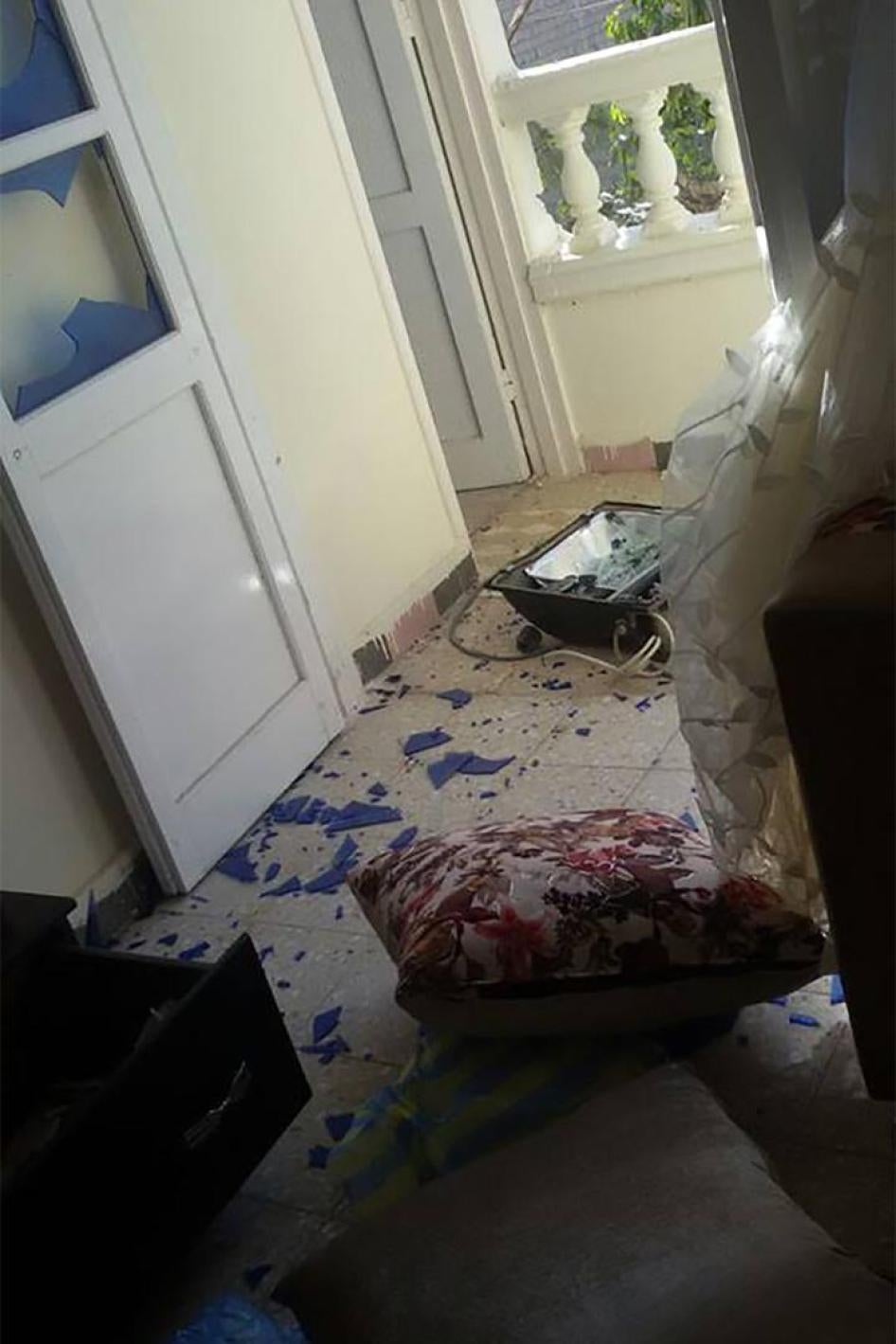

Rashid’s relative said that neighbors later told her that there had been at least 15 armored vehicles and police vans outside her home during the raid. The security forces searched the two apartments and destroyed most of the family’s property, including the bed, refrigerator, television, toilet, stove, and glass cupboards. Police also took three mobile phones and about 2,000 Egyptian pounds (US$119), the relative said. The family sent Human Rights Watch photos of the damage.

Rashid’s wife, who was one-month pregnant at the time, yelled at the police that these were new furnishings and that she was recently married. An officer told her, “Come, see your things while they’re being destroyed,” she said. Another officer grabbed her and pushed her against the wall twice. She said that she later suffered a miscarriage, but Human Rights Watch was not able to obtain any medical documentation.

Two days later, security forces returned to their street and arrested more residents. When Rashid’s wife approached the officers to ask them about Rashid, one of them told her, “He will never see the street again. Find another husband.”

On January 13, the day of the alleged raid, Rashid’s family had no internet connection, but friends called and told them that they had seen Rashid name in the statement.

“I didn’t believe it,” Rashid’s relative said. “I thought maybe it was a false statement or something.”

Rashid’s relative said that he had been close friends with one of the other six men named in the Interior Ministry’s statement and killed in the alleged raid, Abd al-Aty Ali Abd al-Aty al-Deeb, who was arrested about nine days before Rashid.

“Here [in North Sinai] you can’t breathe,” the relative said, describing the way security forces treat civilians. “You can’t ask [officers] to present an arrest warrant.”

He said that he had inquired about Gam’a in some police stations but that they had denied that Gam’a was there. The family did not receive any information about Gam’a until the Interior Ministry statement on January 13.

The relative said that anyone involved in the violent acts alleged by the Interior Ministry would not have stayed at their home like Gam’a, who had wanted to have children and sought regular treatment for his infertility.

“We did not send any faxes [to the authorities] … We thought he would go back home soon because he is a straight, clean guy,” the relative said. “We didn’t know it would reach this level.”

Abd al-Aty Ali Abd el-Aty al-Deeb

The Interior Ministry accused Abd al-Aty, 25, of involvement in the killing of Mohamed Mostafa Ayad, an engineer who had performed work for the armed forces and was kidnapped by unknown armed men in September 2016 and publicly shot to death five days later in a main square of al-Arish, according to media reports and activists on Facebook.

Ayoub, the lawyer who is representing Abd al-Aty’s and Rashid’s families, said that security forces arrested Abd al-Aty on October 8 and that the families had retained him about two weeks later.

Ayoub was at the Ismailia morgue when some of the men’s bodies were delivered to their families, and he said that both Abd al-Aty and Rashid appeared to have been shot once in their heads. He also said he saw burns on Abd al-Aty’s body and bruising on the wrists that he believed were signs of handcuffs. Human Rights Watch viewed photos of the two bodies but could not independently confirm the existence of bullet wounds to the men’s heads. Schmitt, the forensic expert, said he could not confirm the cause of the marks, but that Abd al-Aty’s body appeared to have had a full autopsy.

Ayoub filed a complaint to prosecutors, also viewed by Human Rights Watch, on behalf of both Abd al-Aty’s and Rashid’s families a few days after their deaths, which accused Interior Ministry National Security officers in al-Arish of forcibly disappearing and killing the two men. Prosecutors have not responded, he said.