When the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development published its draft hate crimes bill for public comment, it meant that the government was finally ready to punish bias-motivated crimes. But the cause for celebration is also cause for consternation.

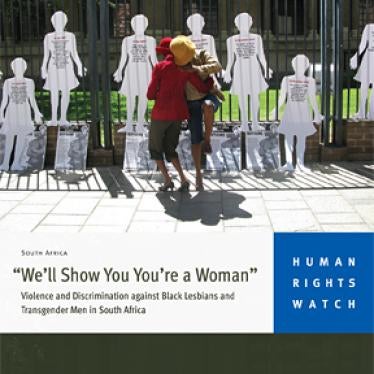

The draft includes an over-broad and vague provision criminalizing hate speech that threatens freedom of expression, a fundamental human right. That is not to say hate crimes legislation is not necessary; it is and it should be welcomed. South Africa faces a scourge of racist and xenophobic attacks, sexual violence and commonplace murders of black lesbians and transgender men, as a 2012 Human Rights Watch report documented. And the violence continues, most recently the December 5, 2016 report of an assault, abduction and murder of a black lesbian, Noluvo Swelindawo, in Driftsands near Khayelitsha in Cape Town.

The inclusion of race as a basis in the draft hate crimes law is especially significant. As recently as November 7, 2016, two white farmers carried out a horrific attack on a black man. The accused, Willem Oosthuizen and Theo Martins Jackson, were charged with assault and intent to cause grievous bodily harm in a Middleburg court after a video emerged online showing them pushing Victor Mlotshwa into a coffin and threatening to burn him alive. The accused have been denied bail. The Human Rights Commission is monitoring the proceedings in the criminal court.

Racist speech is particularly troubling considering the legacy of apartheid. Indeed, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed grave concern about the absence of legislation to tackle hate crimes and hate speech in South Africa and encouraged the government to pass a law that complies with international human rights norms and standards. However, in its current form, the hate speech provision is too broad and may give rise to serious violations of freedom of expression.

There are other avenues to address hate and racist speech other than creating broad, damaging criminal offenses. The Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act not only prohibits hate speech, but section 10(2) also already empowers the court to “refer any case dealing with the publication, advocacy, propagation or communication of hate speech” to the National Director of Public Prosecutions for criminal proceedings.

A case in point—back in 2009, the South African Human Rights Commission brought a case in the Equality Court over an article with the headline “Call me names, but gay is not okay.” Fast-forward seven years, and the case – and the author’s constitutional challenge to section 10 (hate speech provisions) of the Equality Act remain unresolved.

While the expression of controversial ideas and opinions about lesbian and gay people should generally be regarded as legitimate exercises of the right to freedom of expression in a free and democratic society, the South African Constitutional Court has explicitly recognized that lesbian and gay people are a vulnerable section of society who have historically experienced widespread discrimination and prejudice.

When the complaint was filed, lesbian and gay organizations were routinely dealing with reports of sexual violence and murder of black lesbians and transgender men. But even in a case in which speech clearly could do harm, overbroad provisions will not produce justice.

The Hate Crimes Bill did not originally criminalize hate speech, but the Justice Department argued for its inclusion, citing recent racist comments on social media. But existing laws, in particular the Equality Act, deal adequately with hate speech and additional legislation is unnecessary and unjustified. The South African government can address the emerging and deeply troubling trend of racist speech by ensuring that ordinary South Africans are able to file cases under the Equality Act and that the Human Rights Commission has the resources to pursue and monitor the cases.

The government should adopt and effectively implement hate crimes legislation, but can and should do so in a way that ensures the criminal law only applies to the most serious cases, involving criminal behavior such as violence. The expression of controversial ideas or opinions, no matter how offensive, when made without incitement to violence should be regarded as legitimate exercises of the constitutionally and internationally protected right to freedom speech.