Aniket Khicchi and Ratan Vani were arrested on October 26, 2013, for alleged theft and taken to the Vanrai police station in Mumbai’s Goregaon neighbourhood. Khicchi died that night. The police did not inform Khicchi’s family either of the arrest or of his death. The police said that Khicchi, 20, had tried to run away, and when he fell, an angry mob had beated him up, resulting in severe injuries that led to his death. His family disputed that story, and said he died from beatings by the police.

In January 2016 four constables were convicted for torturing Khicchi, causing his death in police custody.

In handing down guilty verdicts, Judge SM Bhosale noted, “The word ‘custody’ implies guardianship and protective care. Even when applied to indicate arrest or incarceration, it does not carry any sinister symptoms of violence during custody.” The four policemen were each sentenced to seven years in prison for culpable homicide not amounting to murder and for voluntarily causing hurt to extract a confession.

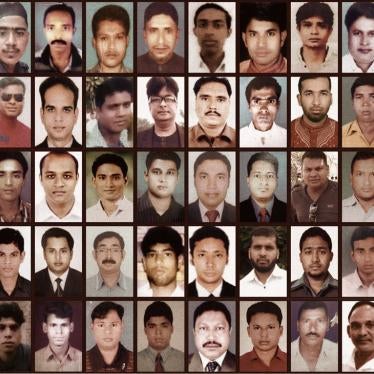

This was a rare case because usually in India deaths in police custody are successfully passed off by police investigators as suicides, natural deaths, or deaths caused to illness. As a new Human Rights Watch investigation into 17 deaths in police custody that occurred between 2009 and 2015 shows, a lack of eyewitnesses, the propensity of government doctors to back dubious police claims in autopsy reports, police intimidation of victims’ families and witnesses, and weak and biased police investigations have provided police broad impunity for crimes against those who are held by police.

Khicchi’s case points to both the challenges in prosecuting police officers as well as recommendations for reform.

Marshalling Evidence

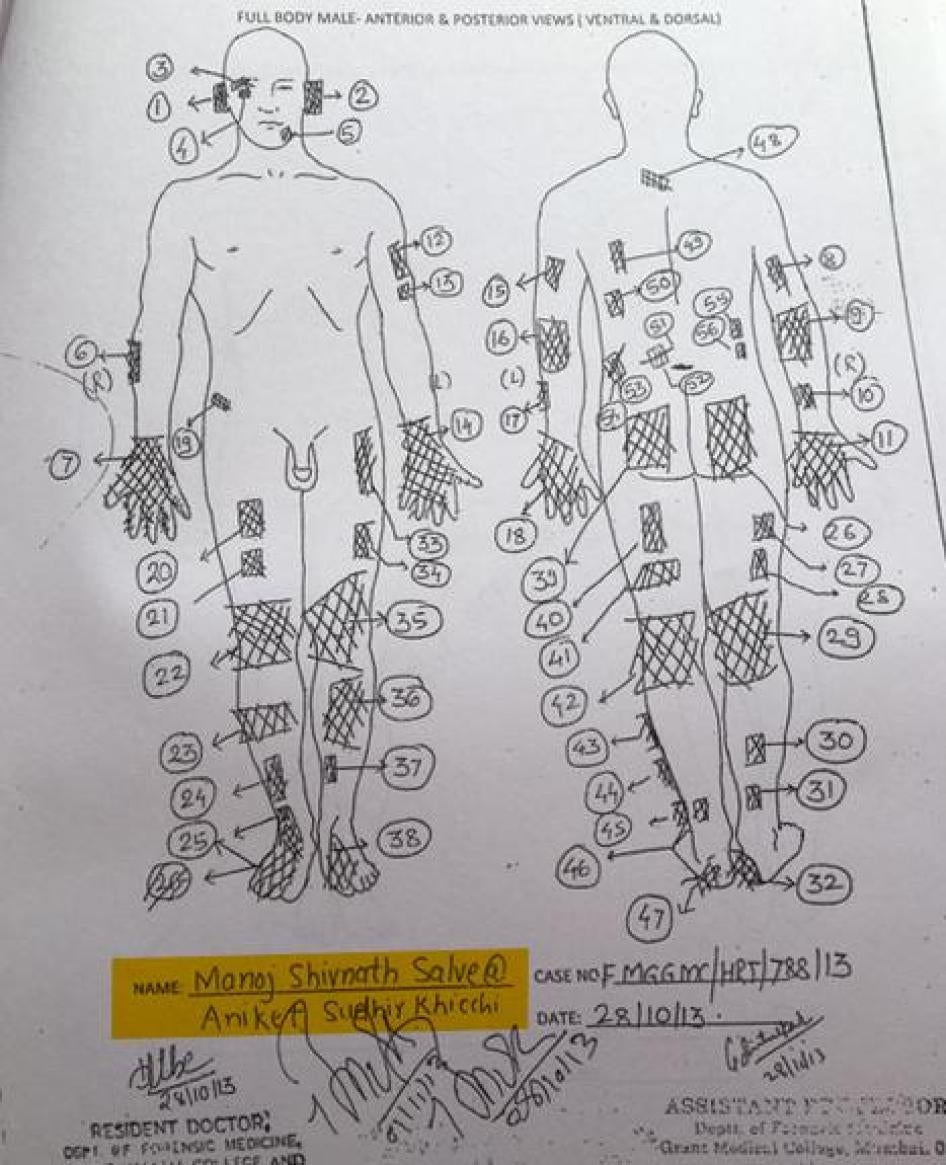

A critical piece of evidence in this case was the postmortem report. A postmortem report is the “most valuable record” for drawing conclusions about how a death occurred, according to the National Human Rights Commission. Khicchi’s post-mortem report shows 56 injuries and final cause of death as “head injury with multiple injuries.” According to the report, all contusions were caused by a hard and blunt object.

When the police attributed those injuries to a mob attack, Khicchi’s family members urged the police commissioner to transfer the investigation to an independent agency. In October 2013, the crime branch of the state Criminal Investigation Department took over the case. A month later, the crime branch filed charges and arrested four police officers on murder charges.

Another significant piece was the court’s willingness to bypass the regular public prosecutor and appoint a special public prosecutor after Khicchi’s lawyer, Mihir Desai, argued that he could not trust public prosecutors. “If we didn’t get a special public prosecutor, I am doubtful whether a conviction would have happened,” Desai said. “Half the time as a public prosecutor, you are taking instructions from the persons who are now the accused.” Too often, public prosecutors, who are officers of the court and are supposed to represent the state, show a bias in favor of police accused of wrongdoing.

In Khicchi’s case, the court noted several procedural violations at the time of arrest. The arrest record was drawn up at 2.40 pm on October 26, but the policemen who took the two suspects into custody did not register a First Information Report or make an entry into the police station diary as required by law until after 8 pm. Until that time, Khicchi and Vani were illegally detained and interrogated inside the police station. The court also said that even though the accused police officers claimed that Khicchi was assaulted by a mob and that they had rescued him from about 60 to 70 people, the policemen did not take him for the required medical check-up.

Protecting Witnesses

However, the prosecution wasn’t without the usual challenges in such cases. The biggest challenge was getting witnesses to testify to torture who are often other police officers or criminal suspects present at the time in the police station. Said special public prosecutor Rati Amrolia, “The fact that most key witnesses are policemen themselves, they are never supportive of any aspect of prosecution’s case. All police witnesses that were material to us turned hostile. Even independent witnesses turn hostile because of the intimidation by police.”

Amrolia said they were fortunate because they had an eyewitness in the case, Vani, who was arrested along with Khicchi. Vani’s testimony played another important role in ensuring the conviction of the accused police officials.

“How I wish to hear the same verdict in my son’s case,” said Leonard Valdaris, father of 25-year-old Agnelo Valdaris, who also died from torture in police custody in Mumbai.

Valdaris’s hope is echoed by many families who lost their loved ones to police torture. Police accountability and enforcing existing rules on arrest and detention are essential to deter further abuses, but changing the culture of torture will also require training police officers in modern, non-coercive methods of investigation and implementing pending police reforms from the 2006 Supreme Court judgment in Prakash Singh v. Union of India. The Indian government should also enact an effective victim and witness protection law to protect them from threats, intimidation, and harassment.

The police cannot change in the absence of fundamental reforms to modernise, including recruiting more police investigators, improving the working conditions of low-ranking personnel, and establishing functioning complaints authorities to inquire into allegations of serious misconduct, including custodial deaths.

As Judge Bhosale reflected on police actions in his judgment: “If you for once forfeit the confidence of your fellow citizen, you can never regain the respect and esteem for the whole police department.”

This is the last in a three-part series looking at torture and deaths in police custody and the urgent need for police reform in India. Read the first part here, and the second part here.