“He was crying bitterly, he was saying, ‘Daddy save me, save me. They have been beating me the whole night. They will kill me, Daddy. These policemen will kill me.’”

Leonard Valdaris, father of 25-year-old Agnelo, is haunted by the last words his son ever said to him. Agnelo died in police custody in Mumbai on April 18, 2014, two days after being arrested.

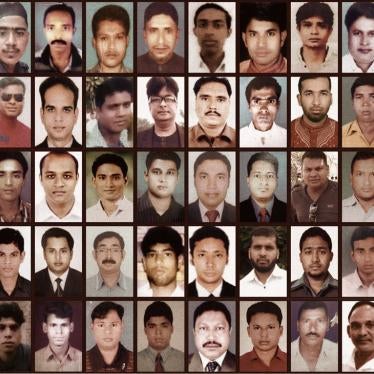

Agnelo Valdaris’s arrest, his treatment in police custody, and the police investigations into his death tell a chilling story of how police in India flout legal procedures, use torture against suspects, and then shield perpetrators responsible for such abuses. As part of an investigation into 17 cases of deaths in police custody between 2009 and 2015, Human Rights Watch examined legal and medical records related to Valdaris’s arrest and death, and statements made by doctors, police officials, witnesses, and others to the investigating agencies.

Torture in Police Custody

Police from Mumbai’s Wadala railway station arrested Agnelo Valdaris from his grandparents’ home around 2 am on April 16 on suspicion of robbery. Three others, Sufiyan Mohammad Khan, 23, Irfan Hajam, 19, and a 15-year-old boy whose name is withheld for his protection, were arrested for the same crime.

The police allegedly beat and sexually abused all four suspects to confess to robbing two gold chains, three gold rings, some cash, a lunch box, and spectacles from a man traveling in the local train. Hajam, in his statement to the Central Bureau of Investigation, said that he was stripped, tied up and hung upside down with an iron rod inserted between his legs and arms, and then beaten with a wooden stick and belt. He alleged that the policemen attempted to rape him with a wooden stick and threatened to burn his genitals with petrol. He also said he was forced to perform oral sex on the other suspects, with police threatening to beat him up further if he refused.

Hajam and the other co-accused said they also witnessed the police torturing Valdaris. The police beat him with a stick and belt, and kicked him repeatedly in his chest.

Disregard of Legal Safeguards

An examination of records in this case show police flouted multiple legal procedures that are aimed to protect criminal suspects from abuse.

The police violated the Supreme Court’s 1997 directives under D.K. Basu v. West Bengal, now incorporated into the Code of Criminal Procedure, which require officers to identify themselves clearly when making an arrest; prepare a memo of arrest with the date and time of arrest that is signed by an independent witness and countersigned by the arrested person; and ensure that next of kin are informed of the arrest and the place of detention.

The rules require those arrested to be medically examined after being taken into custody, with the doctor listing any pre-existing injuries – any new injuries will point to police abuse in custody. Another important check on police abuse is the requirement that every arrested person is produced before a magistrate within 24 hours. The magistrates have a duty to prevent overreach of police powers by inspecting arrest.

Valdaris and his friends were detained in violation of the law. The police officially recorded Valdaris’s arrest more than 36 hours after he was taken into custody. An assistant sub-inspector of police, who was on duty at the Wadala railway police station that night, later told the Central Bureau of Investigation that he deliberately made incorrect entries in the police general diary on the directions of his senior officer to cover-up the actual date and time of arrest.

Police did not produce Valdaris before a magistrate within 24 hours as required by law. On the evening of April 16, Leonard Valdaris wrote a letter to the Mumbai commissioner of police about his son’s detention. “Till now they have not produced him in any court in Mumbai. I do not know about his whereabouts,” he wrote. The next day, Leonard filed an application in the metropolitan magistrate central railway court asking the court to direct the Wadala railway police to produce his son in court. The court ordered Agnelo Valdaris to be immediately presented in court. However, although police admitted to the arrest, they did not produce him in court saying that they had taken him to the hospital for the mandatory check-up.

Police also violated rules by waiting 38 hours after his arrest before taking Valdaris for a medical check-up. During his check-up Valdaris complained to the doctor that he was assaulted by police officials while in custody. The doctor later told the CBI that the police put pressure on him to prepare a medical report favorable to them by writing that Valdaris’s injuries were self-inflicted.

Lastly, the police violated India’s Juvenile Justice Law. After arresting the 15-year-old boy, the police should have placed him under the charge of a special juvenile police unit or the designated child welfare public officer instead of holding him in regular police custody.

Evading Accountability

After Valdaris died in their custody, the police sought to evade responsibility.

First, they altered police records of the date and time of arrest because they had flouted a key safeguard: producing suspects before a magistrate. In most of the custodial death cases documented by Human Rights Watch, those arrested died within hours of their detention and therefore were never produced before a magistrate. National Crime Records Bureau data from 2010 to 2015 shows that 416 of 591 people who died in police custody died before police obtained an order from a magistrate authorising their custody.

They then attempted to alter medical records. After both Valdaris and the attending doctor refused to accept that the torture injuries were in fact self-inflicted, the police threatened Valdaris’s father into signing a false statement. Leonard Valdaris said he gave a written statement to the hospital that his son’s injuries were self-inflicted under threat from the police that if his son’s statement regarding torture was not withdrawn, they would not produce him in court.

However, the police still failed to produce Valdaris in court, reporting next morning that he died after being struck by a train when trying to flee custody.

“The police personnel killed my son because they were scared that he was going to complain about the torture to the magistrate,” Leonard Valdaris said.

Initial investigations into Valdaris’s death by state police attempted to shield the police officials responsible. Valdaris’s co-accused, who witnessed the torture, complained to senior police officials that they were intimidated and threatened by the investigating officer.

They, along with Leonard Valdaris, filed a petition in Bombay High Court asking that the investigation be handed over to the CBI. In 2016, the CBI filed charges against seven policemen and a policewoman for criminal conspiracy, fabricating evidence, negligence, voluntarily causing hurt, and wrongful confinement under the penal code – but not murder, concluding that Valdaris died because of being hit by a train. It also filed charges against three of them for aggravated penetrative sexual assault and sexual harassment of the 15-year-old under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act. The trial has yet to begin.

Leonard Valdaris says he is paying the price for trusting the police to carry out their duties lawfully. “I fully cooperated with the police, trusting them. I handed my son over to them. Now I am carrying the guilt every day. Had I not given my son to the police, he would have been alive.”

This is the first in a three-part series looking at torture and deaths in police custody and the urgent need for police reform in India.