(Beirut) – A new law drafted by Egypt’s parliament would effectively prohibit independent non-governmental groups in the country by subjecting their work and funding to control by government authorities, including powerful security agencies, Human Rights Watch said today.

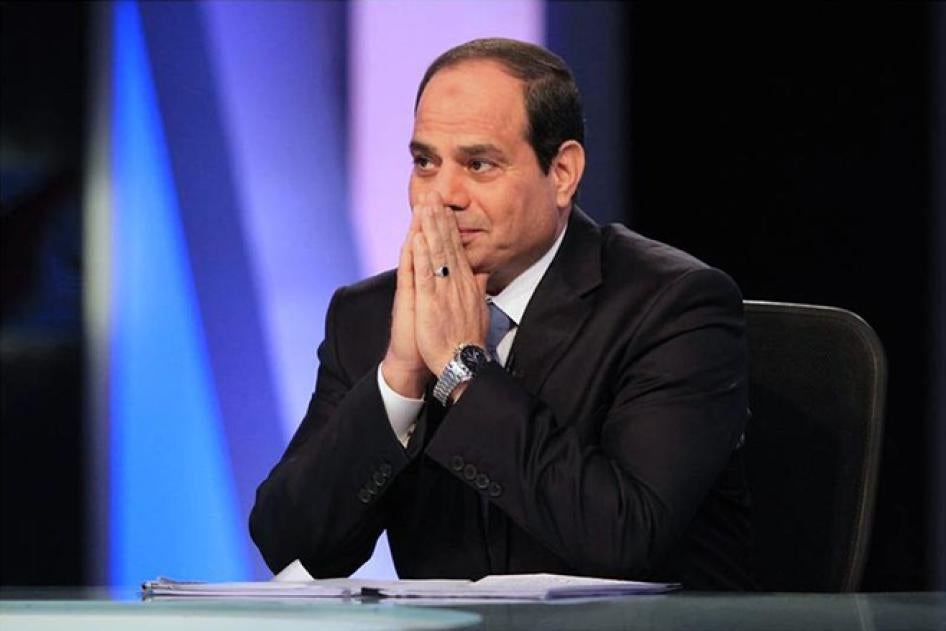

On November 28, the State Council, a judicial body that reviews legislation, approved the draft, paving the way for parliament to send it immediately to President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to sign into law. Members of parliament wrote and discussed the draft behind closed doors before formally presenting it for debate on November 14, 2016, and approving all 89 articles the following day.

“Egypt’s parliament is trying to dodge public scrutiny by rushing into force a law that would effectively ban what remains of the country’s independent civil society groups,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “If this law passes, it would be a farce to say that Egypt allows ‘non-governmental’ organizations, since all would be subject to the security agencies’ control.”

Al-Sisi should decline to sign the legislation, and the government should prepare a new draft with input from independent non-governmental organizations that conforms with Egypt’s constitution and international law, Human Rights Watch said. Maina Kiai, the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association, said on November 23 that the law would “devastate the country’s civil society for generations to come and turn it into a government puppet.”

The draft resembles one proposed by al-Sisi’s government in 2014 and shelved after broad criticism, including from Human Rights Watch. This draft goes even further in some respects, raising the maximum prison sentence for violating the law to five years and requiring that a group’s work would “agree with the state’s plan, development needs and priorities.” Parliament apparently ignored a different draft submitted to it by al-Sisi’s cabinet in September. That draft contained many of the same onerous provisions but did not provide for prison sentences for violating the law.

Parliament’s draft law would criminalize a host of broadly-worded activities, including conducting public surveys or field research without government approval, or conducting any work “of a political nature” or “within the scope” of political parties or workers’ unions. The draft does not define those terms, leaving them open for interpretation by the authorities.

The law would affect 47,000 local and 100 foreign groups working in Egypt, according to government estimates. Nasser Amin, a member of the quasi-governmental National Council for Human Rights, called the draft “disastrous.”

The Law on Civil Societies and Foundations and Other Entities Working in the Civil Sphere, as the current draft is called, comes at a time when Egyptian authorities are investigating dozens of independent human rights groups on allegations that they illegally received foreign funding, a crime under article 78 of the penal code, which al-Sisi amended in 2014 to carry a possible 25-year sentence.

A Cairo criminal court presiding over the politically motivated investigation, which targets human rights groups critical of the government, froze the assets of three groups and five human rights defenders in September. The authorities have also banned more than a dozen prominent human rights defenders from leaving the country, a likely prelude to filing criminal charges.

In November alone, three human rights defenders were told by Cairo International Airport authorities that they could not travel: human rights lawyer Ahmed Ragheb, women’s rights defender Azza Soliman, and anti-torture activist Aida Seif al-Dawla. Dr. Seif al-Dawla cofounded the Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence and Torture, which was ordered to shut down in February. The government froze its assets earlier in November. Dr. Seif al-Dawla received the top Human Rights Watch honor in 2004.

Parliament’s law would forbid nongovernmental groups from working without permission in government-defined “border areas,” including parts of the Sinai Peninsula where the government has conducted an abusive counterterrorism campaign, and the southern border with Sudan, where Nubian groups have protested for the right to return to their ancestral lands. The government’s refusal since 2013 to allow most journalists or any human rights groups into North Sinai, where much of the fighting has taken place, has made it extremely difficult to determine whether the armed forces are adhering to international law.

The law would create a 10-member government regulatory committee, the “National Regulatory Agency for the Work of Foreign Nongovernmental Organizations,” which would have the authority to examine field research before it is published and to approve any agreements between local and foreign groups, including the receipt of funds. The agency would include representatives from the Defense and Interior Ministries as well as the General Intelligence Service, Egypt’s top spy agency.

The draft law would require groups to apply to the regulatory agency for permission to receive foreign funding. Unlike the current law on associations, which dates to 2002, a lack of response from the regulatory agency within 60 days would be considered a denial, not an approval. The law also would subject groups’ bank accounts to Central Bank supervision and ban groups from sending money outside Egypt without approval from the regulatory agency. Agency representatives would have the right to inspect a group’s work and funds at any time and to ask a court to dissolve the group, suspend its work for a year, or replace its board if it violates any of the funding rules.

Any violation would be punishable by up to five years in prison and a fine of up to 1,000,000 Egyptian pounds (US$65,000). Any group that does not register under the new law within six months would be automatically dissolved.

Since 2013, when al-Sisi led the military overthrow of Mohamed Morsy, Egypt’s first freely elected president, the authorities have prosecuted thousands of people for peaceful opposition to the government, including for protesting, mocking al-Sisi and his policies, or advocating better detention conditions. Under al-Sisi, prosecutors have interpreted a wide range of activities protected under the Egyptian constitution and international law as threats to national security and have filed charges against people solely for belonging to opposition movements.

The draft’s criminalization of work or research that harms “national security, national unity, public order or public morals” without narrowly defining those terms in line with international law would allow authorities to use the proposed law to file charges against almost any group, Human Rights Watch said.

Article 75 of Egypt’s constitution states that “[a]ll citizens shall have the right to form non-governmental associations and foundations on a democratic basis, which shall acquire legal personality upon notification. Such associations and foundations shall have the right to practice their activities freely, and administrative agencies may not interfere in their affairs or dissolve them, or dissolve their boards of directors or boards of trustees save by a court judgment.”

Article 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and article 10 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, both of which Egypt has ratified, protect the right to freedom of association.

Under the ICCPR, Egypt may only limit this right through regulations “prescribed by law and that are necessary in a democratic society.” Any limitation should respond to a pressing public need and reflect basic democratic values of pluralism and tolerance. “Necessary” restrictions must also be proportionate – that is, carefully balanced against the specific reason for imposing the restriction and not discriminatory, including on the grounds of national origin, political opinion, or belief. No restriction should undermine the essence of the right to freedom of association itself.

During Egypt’s Universal Periodic Review at the United Nations Human Rights Council in March 2015, Egypt’s delegation accepted recommendations to issue a new associations law that would “fully guarantee to the civil society a set of rights in conformity with international standards,” and to “fully implement its international obligations to ensure the protection of human rights defenders and other civil society actors.”

“It is absolutely essential for President al-Sisi to reject this strong-arm maneuver by parliament and assert his prerogative to draft a new law with input from Egyptian organizations,” Whitson said.