A trial of the five men charged with the 9/11 attacks is still years away – a fact that became obvious while sitting in on last week’s pre-trial hearings in the Guantanamo Bay military commissions.

The co-defendants were arraigned in May 2012, yet the parties are still arguing over what evidence the defense is even entitled – one of many unresolved issues that may drag out pre-trial hearings for years to come.

This week’s oral arguments revolved around the destruction of evidence related to the defendants’ secret detention and torture by the Central Intelligence Agency.

In May, it was discovered that the judge in the case, Col. James Pohl, approved the prosecution's request – made without the involvement of defense lawyers – to destroy unique evidence related to a CIA “black site.” The judge conducted the proceedings about the request and ordered the evidence’s destruction without the defense even being notified.

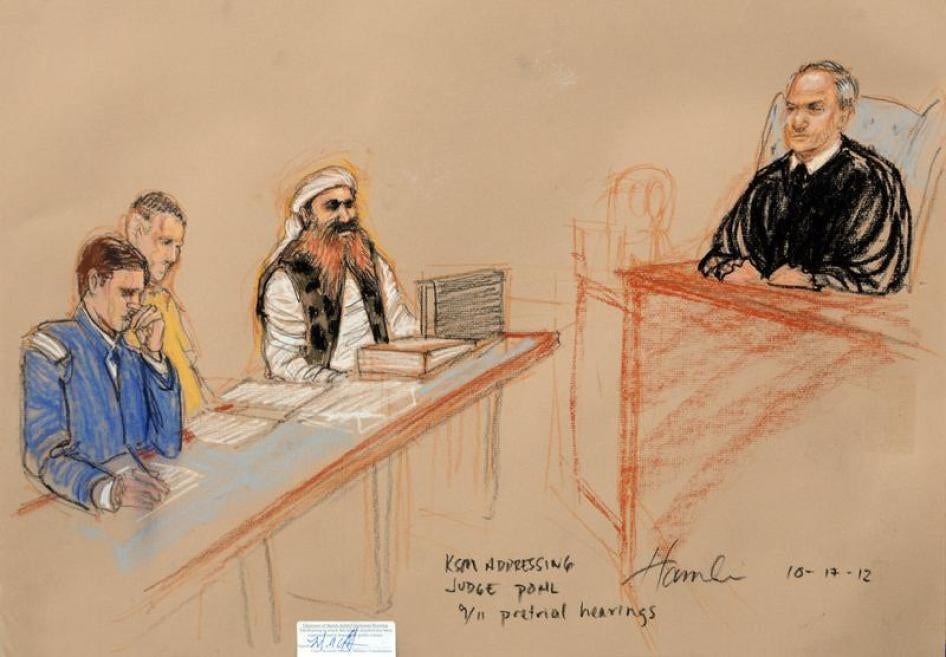

In fact, the destruction of evidence might never have come to light if not for James Connell, attorney for co-defendant Ammar al-Baluchi, who noticed a discrepancy in the court documents and figured out what had happened. At this week’s hearings, David Nevin, attorney for co-defendant Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, argued that Pohl and the prosecution team should be disqualified from the case because of their role in the destruction of evidence. I listened for hours to arguments over whether the judge can rule on his own disqualification – a procedural issue critical to the case but so far removed from the facts of the September 11, 2001 attacks that I wonder how this court will ever come to set a trial date.

The secret destruction of evidence – which defense attorneys said on Sunday involves the decommissioning of a CIA “black site” – is just one of many disturbing incidents that have bogged down the military commission. Other incidents over the years raising fair trial concerns include the disappearance of documents from a computer system designed to handle the case’s classified information; the revelation that listening devices disguised as smoke detectors were found in attorney-client meeting rooms, and an investigation that lasted more than a year over the propriety and consequences of attempting to turn members of the defense teams into informants for the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

This immensely important case should have been tried in New York, where the crime happened, where federal courts have jurisdiction, and where many of the victims’ family members live. Congress should lift the ban on transfers of detainees from Guantanamo to the United States, at the very least to face trial in federal courts.

It’s not too late to move this case. After all, a trial is still years away.