Being a police officer in Rio de Janeiro can be difficult and dangerous. Dozens are killed each year, many at the hands of the heavily armed criminal gangs that control neighborhoods in much of the state.

But it’s not just the gangs that put police officers’ lives at risk. It’s also their fellow officers.

During the past six months, I interviewed more than 30 Rio police officers about their experiences in high-crime neighborhoods. They described being afraid not only of gang members but also of police officers who engage in crime and illegal violence.

One, whom I’ll call “Danilo,” told me he’d participated in several operations designed to kill, not arrest, suspected gang members. During one such operation, an officer approached an injured man who was lying on the ground and shot him dead point blank, Danilo said. “I did not report what happened because I was afraid of being killed myself. Those people have no scruples.”

Two other officers I interviewed also struggled with a choice between reporting their fellow officers or keeping quiet about--and thus becoming complicit in--extrajudicial executions. Both said they were afraid they’d be killed if they talked.

So they didn’t.

Illegal killings by fellow officers hurt police officers who want to abide by the law in other ways. Cornered gang members are less likely to surrender peacefully to police if they believe they will be executed. Community members are less likely to help police whom they fear and distrust.

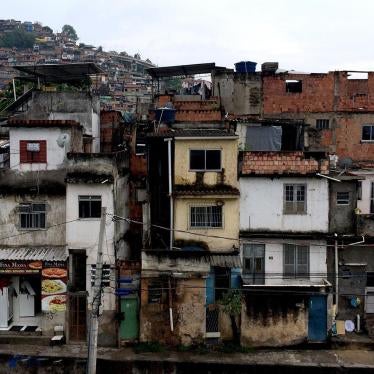

An officer I’ll call “Laura” said that when citizens trust the police, they can help avert ambushes. They “sometimes warn us, don’t go that way.” But in late 2015, a video appeared that squandered that trust and made Laura feel “very vulnerable.” It showed her fellow officers faking a shootout to cover up an unlawful killing in Morro da Providência favela, where she works. “I know I do the right thing in my work,” she said, “but I feel people’s looks of distrust and contempt.”

Unlawful killings are not just a problem of a few bad apples. In some battalions, abusive conduct is expected. “Killing criminals was required as good performance by my superiors,” Danilo said.

The blame does not fall solely on military police. Civil police officers and prosecutors who fail to investigate such cases properly, and members of the public who applaud when police kill, do a great disservice to the Rio police. Criminals in police uniform who go unpunished endanger the rest of the force.

Last January, I spent a morning with police officers doing community outreach at Mangueira favela. They flew kites with kids in a soccer court. The children were laughing, but wary. On a wall by the court, somebody had scrawled: “A good cop is a dead cop.”

I asked the kids what they thought of the police. “They are bad. They kill innocent people,” said a boy of about 9. A few feet away, three police officers with neither bullet-proof vests nor assault rifles stood watching the kids, trying to do the right thing.