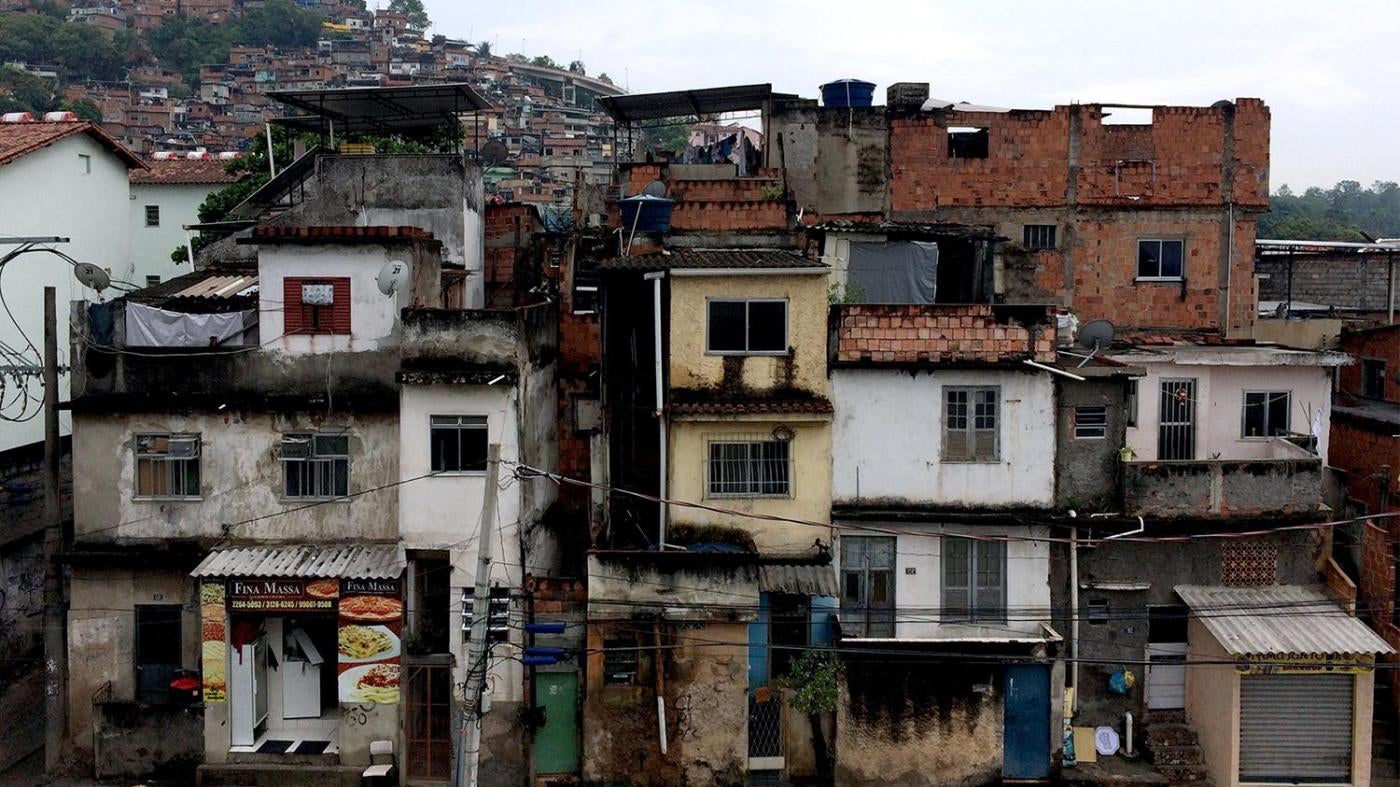

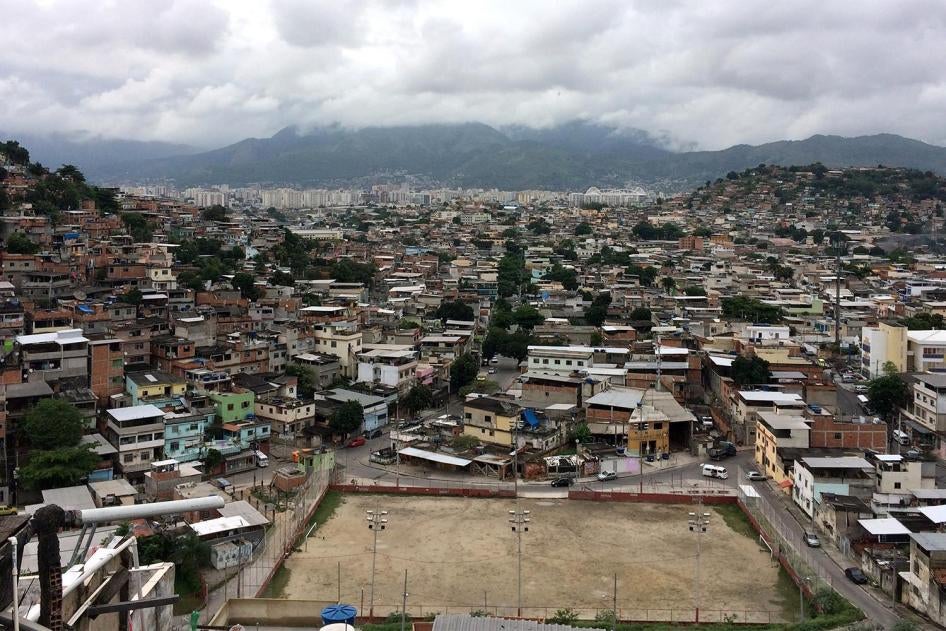

Cesar Muñoz and João sat down in the living room to talk. Cesar knew a little about João – he worked as a military police officer in Rio de Janeiro, the type of police who regularly storm into the city’s 1,000 or so favelas, or slums, with assault rifles and armored vehicles.

Cesar, the Human Rights Watch Brazil senior researcher, didn’t know that what was to come was one of the most shocking interviews of his life.

In the beginning João talked about relatively minor misconduct (by Rio de Janeiro standards), like keeping guns confiscated from suspects that should have been handed over as evidence, but it didn’t take long before he told of torture and murder.

When he committed these crimes, João was a member of a tactical unit within a battalion—a Tactical Action Group (GAT, Grupamento de Ações Táticas). “To remain a member, you have to kill and confiscate weapons,” he said.

Cesar took notes, hiding how unnerved he was at the casual way João talked about his past. João was handsome, his hair cut short like a cop, and spoke intelligently and reasonably. He did not seem like a killer.

“I didn’t feel he was someone who would pull a gun and kill me on the spot, although he could,” Cesar said.

They talked for two hours.

A new Human Rights Watch report, Good Cops Are Afraid, details how police like João in the state of Rio de Janeiro have killed more than 8,000 people in the past decade. Police were responsible for one in five homicides in the city of Rio last year; and three quarters of those killed by police were black men. As police often face violence from heavily armed gangs, many killings are self-defense, but many others are extrajudicial executions. These killings turn communities against the police, making the job of policing Rio more difficult and dangerous.

Rio de Janeiro promised that security would be an important legacy of the upcoming Summer Olympic Games it’s hosting in August. But it has not done enough to address extrajudicial executions by police, a central obstacle to more effective law enforcement.

Rio authorities have recently taken several steps to improve how those cases are handled, including creating a special prosecutorial unit focusing on police abuse. However, additional steps are needed to strengthen the new unit and ensure proper investigations and prosecutions of these cases.

João´s story shows how impunity perpetuates police abuses.

At first João described his “small” crimes, like confiscating guns from suspects, then either keeping them or reselling them – sometimes to known drug lords.

João talked as if he were a soldier in a war, and the members of drug gangs were his enemy. “He became more animated when he was talking about combat,” Cesar said.

João mentioned in passing that he’d tortured people, apparently without giving it much thought, as if it was part of his job description, Cesar said.

But torture was important to what Cesar was trying to find out, so he pressed for details. João relayed the facts. He and other officers had chased a few teenagers – they looked to be around 18 – into a house, where they found two guns. “They were very young,” João said.

Suspecting there were more guns, they tortured the teenagers. First, João said, they put plastic bags used to package ice over the youths’ heads to suffocate them. When Cesar asked why an ice bag, João replied, “Because ice bags are stronger, and people can tear regular bags with their teeth.”

Then they beat the youths about the face, kicked them in the ribs, and pepper-sprayed them. When João said they didn’t use electric shock, Cesar asked why. João answered, “We didn’t have a machine available.” The youths were tortured for 20 or 30 minutes, but didn’t reveal the locations of more guns.

“The police have a method” in using torture, Cesar said. “They knew how to do it, had done it before. It was pretty shocking. [João] told the details so matter-of-factly. Like it wasn’t extraordinary.”

As João described the killings, Cesar thought of the families of people killed by police. He couldn’t erase their pain and stories from his mind as he listened to João.

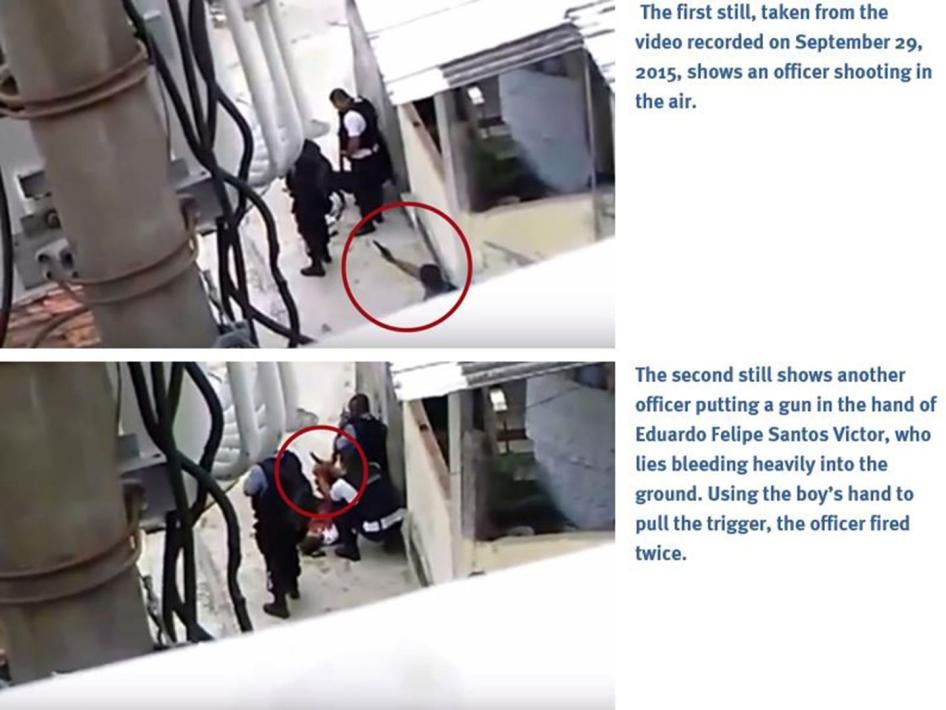

João described an operation in which the objective wasn’t to detain suspects but to kill them. Some officers entered a favela from one side while João and some officers hid in the foliage near a possible escape route. As the suspected drug traffickers ran past, João and his colleagues shot them. They killed one, and another was badly injured but he didn’t instantly die. One of the police officers went to look for guns to plant on the guys. The rest of the officers hung about while the man was dying. “We wanted him to die there,” João admitted.

Once they had the new guns, they fired some shots with them and placed them in the hands of the suspects. After a while, local residents started congregating, and the police decided to leave. They threw the injured man into the back of the car and the dead man on top of him. They took the victims to a hospital, where the second man died.

“It’s a lack of respect for human life that’s just astounding,” Cesar said. “It’s difficult to process, really.”

The approximately eight police officers who participated in that operation went to the civil police station afterward, but only two gave statements. That was their standard procedure after unlawful killings: only two of the officers would report participating in a shootout. They would alternate which two so that none would accumulate a larger record of kills that might appear suspicious.

“The civil police do not ask every person who shoots a weapon to give a statement,” João said. The two police officers told the civil police that they were attacked when they entered the favela and shot back in self-defense, the same narrative they used for all killings, João explained.

Brazil’s favelas are dangerous, and oftentimes ruled by drug lords. Did João see himself as taking down bad guys to end crime?

Not at all, Cesar believes. João and many of his fellow officers took kickbacks from drug traffickers in exchange for not raiding the favelas. When one drug trafficker asked João to kidnap his drug boss so he could climb the crime ladder, João and the other officers complied – and divided the ransom money.

João didn’t join the police force to make money on corruption – rather, he joined for the good career and good benefits, he said. But when he saw the guy next to him doing the same job but making much more money from kickbacks, he decided to join in.

“I see this as very dangerous,” Cesar said. “It really shows that if the military police don’t address the criminal behavior that is prevalent in some battalions, this could happen to anybody. Anyone could become like this.”

João was also under no illusions that people, even other police, were safer because of his actions. If he killed 10 suspected members of gangs, he said, 10 more would replace them. “It’s like trying to dry ice,” João said, using a Brazilian expression.

Today João is a member of a different military police battalion. He told Cesar he would not tell on his former fellow officers. “They would not think even a millisecond before killing me or my family,” he said.

After the interview, João drove Cesar back to his hotel. They talked about nothing in particular. Once again, it was all disturbingly normal.