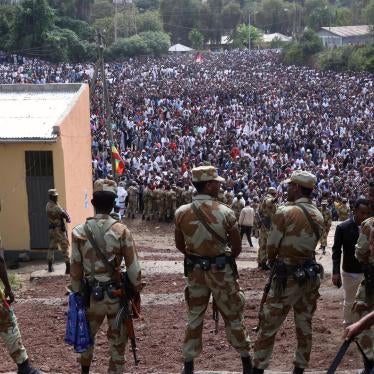

Since November 2015, Ethiopia’s Oromia region has been rocked by widespread protests. State security forces have responded to the largely peaceful protests with lethal force, resulting in the loss of more than 400 lives. Thousands have been wounded. Tens of thousands have been arrested and many remain in detention without charge. Many of those killed or detained by security forces are students. Human Rights Watch’s Birgit Schwarz talks to Ethiopia researcher Felix Horne about what triggered the protests, why the government’s brutal crackdown has received so little attention, and how he went about gathering credible evidence for his latest report, “Such a Brutal Crackdown,” in a highly repressive country that refuses to let in human rights researchers.

What triggered the Oromia protests?

The initial trigger was the Addis Ababa Master Plan, a very ambitious growth plan, which proposed to expand the municipal boundaries of Addis Ababa twentyfold in order to manage the capital’s rapid growth. This would force mainly ethnic Oromo farmers living around Addis to move. Many of these people have repeatedly been displaced from their land over the last decade without adequate compensation. The protests soon spread -- we know of about 500 incidents of protests across all 17 zones of Oromia. Many are taking place in rural areas, where people have been displaced because of investments in commercial agriculture projects.

What options do displaced farmers have?

Ethiopia is a country of 100 million people, with high population density, especially around the capital. As with many expanding cities, there simply is no available land near the capital. So this is a difficult issue to resolve. However, in most cases we found that there was no attempt to compensate or provide alternate land for those farmers. They either have to live with family members elsewhere, flee the country, or go to Addis and search for low-paid work. Some farmers ended up working on their own land as watchmen or laborers.

Ethiopia is considered a development success story. Is this the price of its success?

Ethiopia is making major strides economically and its population does benefit from the country’s growth. But the government has a very authoritarian approach to development. The ruling party occupies 100 percent of the seats in the federal parliament as well as in all regional parliaments. When the government earmarks land for major investment projects, such as sugar or cotton plantations, flower farms, or manufacturing, the communities living on the land are hardly ever consulted and residents are often displaced without compensation. Those who express any kind of dissent are frequently targeted for harassment, arrest or even torture. Ethiopian law has made virtually impossible the operation of independent organizations that can represent victims of abuse or work against injustice. And the courts are not remotely independent when dealing with politicized cases.

Who are the protesters?

Initially the protesters were young, rural secondary and primary school students. They are much more aware of what is happening and of their rights than many in the older generation. University students are also involved. There was a period when the farmers joined in. But the older generation has been through these crackdowns many times; they know there will be harsh consequences if they raise their voices too loud. For example, farmers are largely dependent on the government, which provides fertilizers and in some cases, seeds or food aid. Those who actively speak out against government policy risk their access to these critical resources. So farmers avoid criticizing the government because it puts their ability to grow food in jeopardy.

How did students mobilize in a country that restricts any independent media and where surveillance is pervasive?

“Who is mobilizing? Who is behind this?” were questions the intelligence services constantly put to those they interrogated. Most of the students don’t have an answer. There is no puppet master who is pulling the strings. This has mainly been a spontaneous, grassroots movement. When I asked students how they know what is happening in other parts of Oromia, they said they knew through friends in neighboring villages, through Facebook – before the government restricted Facebook in Oromia – and occasionally through the Oromia Media Network, an independent diaspora television station.

How did the government respond to the protests?

After first responding with local police in Oromia, the government deployed the military, claiming that the protesters had been hijacked by outside forces and were bent on destroying government property. We did indeed find some cases in which protesters acted violently or in which there were attacks on government offices near the protests. But the vast majority of the protests were peaceful. Nevertheless, the security forces made tens of thousands of arbitrary arrests and shot live ammunition indiscriminately into the crowds. Because young children were often at the forefront of the protests, many of those struck by bullets were students. We estimate over 400 mostly young people have been killed since the protests began.

But didn’t the government halt the plan to expand the boundaries of Addis Ababa?

In January the government announced the cancellation of the Master Plan. This was a rare concession for a government that is not used to making them. But by that time, the protesters’ concerns had become much broader. Not only were they talking about the plan, but also about the brutal response of the security forces to the protests, the jailing of students and children, and the decades of discrimination that ethnic Oromo have endured. So the announcement had little impact on the protesters. And the conduct of the security forces did not change either. They have continued to use live ammunition and make mass arrests.

How did you collect and corroborate the evidence for this report?

Surveillance is heavy, sources are targeted, and interpreters are at risk. In some cases, both local and foreign journalists have been detained. Despite this, we did manage to find ways to interview a number of protesters inside Ethiopia. We compared what they said with information given to us by people who had recently fled the country. We corroborated their accounts with photos, videos, police documents, health records. To confirm the authenticity of videos, we checked the footage’s metadata. We also spoke to the people who shot the videos, confirmed who the protesters in the videos were, and interviewed some of them. And we spoke to several local government officials who had fled the country.

We supplemented all of this with information we had gathered over the years for many of the locations where these protests took place. We know places of detention. We know about specific interrogation techniques that have been used. Nothing appears in our report that has not been confirmed by multiple sources.

What are some of the worst atrocities you documented?

Some of the protesters who had been in detention had weights tied to their testicles. We also documented cases of students arrested in their dormitories, blindfolded, taken to unknown places, hung upside-down by their ankles, beaten and told to reveal who was behind the protests.

Which stories moved you most?

There was one 17-year-old student who had gone to the protests not really understanding the issues. When he saw his friend get shot in the chest and go down, bleeding, he just ran and kept running. I interviewed him as he crossed the border into Kenya. One minute, he was worrying about school and his grades. The next minute, he realized that he might never see his family again, all because he joined a peaceful protest.

The other was the story of a young girl from the Arsi zone, a grade 8 student. Of the 28 students in her class, 12 had been arrested and their whereabouts were unknown, 3 had been arrested but later released, 4 had run away, 1 had been shot and killed, and 2 had been injured. When the teacher was arrested, and classes stopped, she fled.

Given the repressive climate, how were you able to protect your sources from retaliation?

We have seen many examples in the past where individuals who supplied information to international journalists and occasionally to human rights organizations were arrested or had to flee the country. The threats are real. Individuals only open up when they believe that we will protect their information and ensure their confidentiality. That’s why we do not supply names of those we interviewed or of locations nor any other detail that could identify our sources.

What effect has the crackdown had on the Oromo community?

Even though the government has cancelled the Master Plan, people remain skeptical. After decades of broken promises, many feel that those announcements are solely made for the benefit of an international audience, and that the government has no real intention to back down on its abusive approach to development.

Most of the mothers and fathers we spoke to have at least one child either in detention or in some refugee camp across the border. Some have no idea what happened to their children. They know they went to the protests, and that was the last they heard of them.

Thousands of student protesters have been forced to flee their homes and have sought asylum in neighboring countries, where they face numerous security risks and economic hardships. Often they find themselves stranded in a country whose language they don’t speak and where they are unlikely to be able to finish their education. For them, the future looks very bleak.

What has the international response been?

The United States and Ethiopia’s other allies like to highlight the regional counterterrorism initiatives Ethiopia is involved in, but turn a blind eye to domestic repression. The fact that Ethiopia hosts hundreds of thousands of refugees, and is the seat of the African Union, makes it even more difficult for other governments to publicly criticize the country’s response to these protests. However, if they continue to disregard the crackdown, Ethiopia’s long-term stability will be at risk. The situation is tense. The kids I talked to just want a future. But after hundreds of students have paid with their lives for taking their grievances to the streets, a growing number of people feel that there is no avenue left for peaceful expression of dissent.

What ought to be done to end the crisis?

The US and other allies should take a much firmer stance against these abuses and let Ethiopia know that it is not ok to arrest tens of thousands of students and shoot at kids who are peacefully protesting. There needs to be an independent, transparent investigation into this crackdown. Since the Ethiopian government has not shown that it is able or willing to conduct such investigations, allied countries and international entities ought to lend their support to ensure that members of the security forces responsible for abuses are held to account, whatever their rank.

This interview has been edited and condensed.