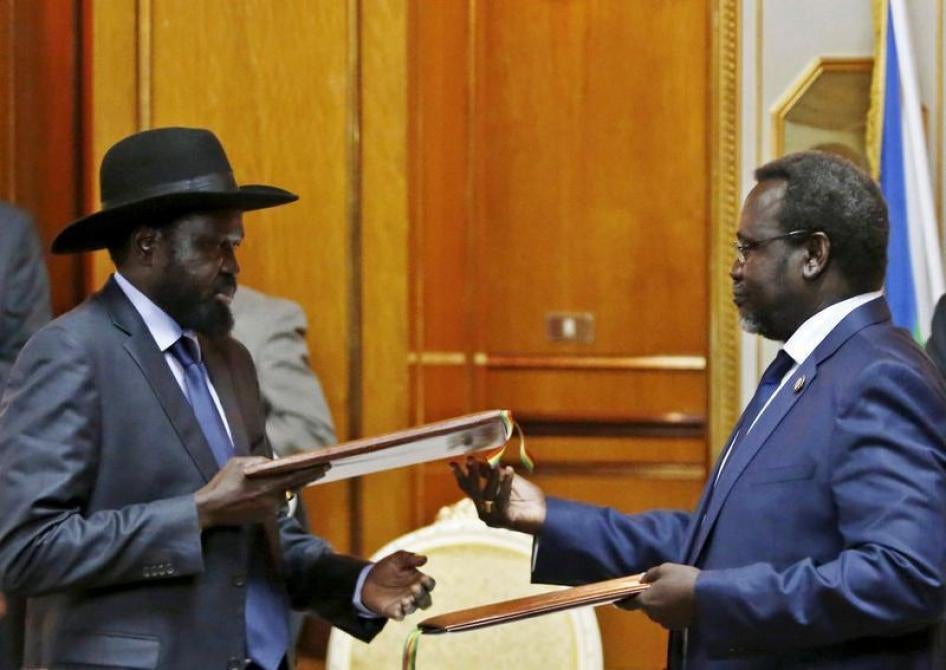

After leading South Sudan into a two-year nightmare, its leaders Salva Kiir and Riek Machar now want to shield themselves and anyone else implicated in wartime atrocities from justice. This week the pair audaciously proposed scrapping the landmark war crimes court envisioned in the peace agreement they signed, and instead focus exclusively on a truth and reconciliation commission.

It is obvious why these leaders want to avoid trials – they were commanders-in-chief of forces implicated in grave crimes in which thousands of people were killed and many hundreds of thousands more displaced, during the country’s bloody civil war.

But their claim that justice “would destabilize efforts to unite our nation” is both outdated and untrue.

Experience over the past two decades – including in Sierra Leone, the former Yugoslavia, and Chile – has shown that criminal trials for wartime atrocities have not undermined peace. On the contrary, the failure to pursue justice often fuels further crimes, such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo and, most recently, Syria.

South Sudan is a prime example of how bad things can get. Despite years, even decades, of atrocities by commanders on all sides, peace deals – including from the North-South conflict – have repeatedly rewarded abusive leaders with plum positions and provided de facto blanket amnesties. Abuse of civilians has been a path to promotion and power.

It is clear that ethnic and political divisions, prompted in part by the failure to account for past horrific crimes, have fueled the brutality that the South Sudanese have endured since December 2013.

And while truth-telling has an important role to play in countries emerging from conflict, it is complementary and not an alternative to a fair hearing before a competent court and imprisonment of those found guilty. Justice not only honors the victims rather than the abusers, it sends a strong signal that atrocities will no longer be tolerated.

On our many research trips to South Sudan, civilian victims repeatedly told us that only justice can truly break their country’s cycle of crime and conflict.

The African Union, which is responsible for establishing the hybrid court under the terms of the peace deal Kiir and Machar now want to dismantle, should press on with its plans for justice regardless. Because history shows that the alternative is likely to be another descent into violence for those who have already suffered so much.