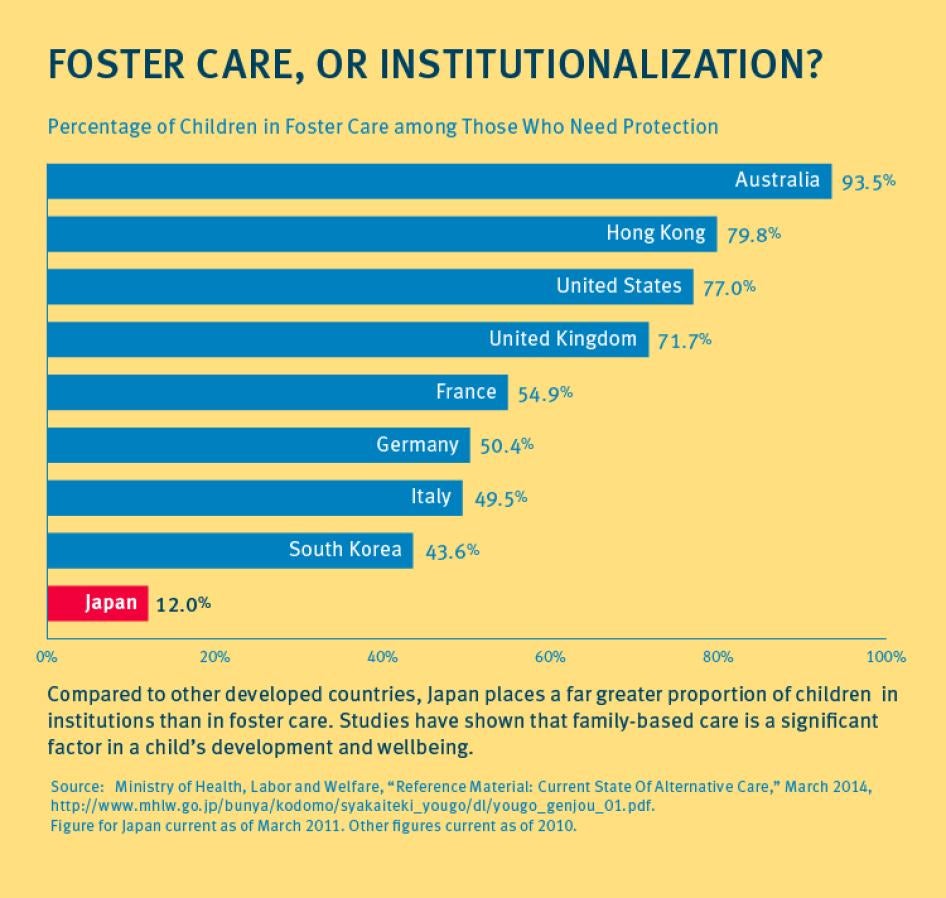

In Japan, the number of children who were removed from their biological families for reasons such as abuse or unwanted pregnancy stands around 39,000. Nearly 90% of these children who are under the “alternative care” system are placed in child/infant care institutions. Only a very small fraction of these children are cared for by foster parents or have been formally adopted, and enjoy family life. As there has been increased awareness of the negative consequences for children from “non-family/over-institutionalization” policies such as Japan’s, the international community has consistently called for deinstitutionalization.

The Contents of the Amended Child Welfare Act

If this revised Child Welfare Act is diligently observed, the alternative care system will drastically migrate from institutions to families. The new Article 3.2 lays out a new “principle of family-based care”, guaranteeing life in a family-setting including adoption and foster care, for all children. Institutionalization is limited only to cases whereby family-based care is “not appropriate,” and even in such case the Article obligates the placement of children into institutions that can provide “the best possible family-like settings.” In light of the current situation within Japan, the newly added Article is revolutionary. Children who cannot live with their biological parents, in particular pre-school children, should now be able to live with new families including via the adoption and foster family system.

In addition, in order to change the current situation where adoption has hardly been utilized within the child welfare administration system, the legal definition of adoption was revised with more clarity, and it is promised that the way to promote its use will also be discussed.

Rights to Live in a Family

In May 2014, Human Rights Watch released the 89-page report, “Without Dreams: Children in Alternative child care in Japan” in which more than 200 people were interviewed across the country. The report criticized over-institutionalization and called for fundamental reform. Human Rights Watch has continued to recommend concrete steps for a systemic reform even after the establishment of a special council on Child Welfare by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in September 2015, including by sending a letter to the Minister outlining such steps.

The Article 20.3 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child lays down a child’s right to live in a family. Therefore children’s alternative care shall be done via adoption and foster care, and institutions are to be used only when necessary. The Committee on the Rights of the Child states that the institutionalization of a child is a measure of last resort, and in 2010 it expressed their concern over Japan’s shortcoming of policies with regards to family-based alternative care.

I don’t have any dreams [for the future].

—Nozomi M. (anonym), 15, living in an institution in Osaka

Most of the staff look like they only take care of us because it is their job. They just play with us as a part of their jobs. They don’t love us.

—Kenji M. (anonym), 17, living in an institution in Tokyo

Challenges for the Future

Bureaucratic decisions that have prioritized various adult matters over the best interests of the child created the existing policies of over-institutionalization. A care worker at an institution in Tsukuba, Ibaraki said “in Japan, the interest of the parents is seen as more important than the interests of the child.” With the new Child Welfare Act, the question now is whether Japan could reverse such trend.

Listed below are the major steps required in the near future.

Being ahead of schedule in the national plan to increase foster parents ratio to 1 in 3

From 2015, the Japanese government has been trying to increase the foster parents rate from the current level of 15%, up to 30+%, as well as reducing the number of institutions down to 2/3 in 15 years (by 2029). Along with the new amendment, the government should review fundamentally its forecasted achievement period, especially for infants.

Prohibiting the new construction of institutions and transferring to resident-based care

It is clear that new construction of institution needs to be prohibited as the system migrates from institutions to homes. In rare cases that institutionalization serves the best interest of the child, the living conditions in those institutions must be changed toward a more resident-based living with smaller facilities (including group homes). The UNICEF handbook on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (page 282) lists such cases: 1) repeatedly failed relationship between the child and foster parents; 2) a large number of brothers and sisters who do not want any separation; and 3) teenager who is going to be 18 soon.

As described in the HRW’s report “Without Dreams”, the conditions of facilities in Japan are very poor. Therefore even in cases where institutionalization is the best option, the living conditions must be changed toward a more resident-based living with smaller facilities (so-called group homes). As a result, new construction of such resident-based child care facilities should be encouraged. At the same time, there is a crucial need to improve the ratio of children and workers as institutions close down, and should aim for 1:1 following international best practices.

Formulating concrete criteria to promote the principle of family-based child care

In order to enforce the principle of family-based child care that was stated in the new amended Act, formulating concrete criteria, in accordance with international standards including the UN Guidelines, that care workers in each local community could refer to is essential. In particular, the criteria at least needs to be effective enough to put an end to the current situation where children are institutionalized because of their parents’ desire to avoid foster care.

Promoting special adoption as the best interest of children

The new amended Act states that the way in which the special adoption system is promoted will be reviewed. To guarantee the persistence of family-based care for all children, a speedy revision of the system to realize the best interest of the child is necessary, while clearly stating in legal provisions the guarantee of permanency.

Some additional measures that need to be taken include: 5) children who have been institutionalized against their best interest should be swiftly transferred to families; 6) the measures concerning the transfer of children with disabilities to home-based care must be reviewed and promoted; and 7) lawyers must be swiftly deployed to all child guidance centers to guarantee the child’s best interest.

For the Next Generation

There are various movements to back up the amendment of the Child Welfare Act at the operational level. In this year’s “Adoption Day” (April 4th), a total of 33 municipalities (11 prefectures and 9 cities) and 13 civil society organizations established the Public Private Forum to Promote Family Environments for Children (Chairman: Eikei Suzuki, Governor of Mie Prefecture) in order to build a society where all children live at home.

More than 20 years has passed since Japan ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states a child’s basic rights to grow in an atmosphere of “happiness, love and understanding” and in a “family environment.” It must be said that the new amendment came too late for children who became adults over the past 20 years. However, in order not to repeat the mistakes for the children who will bear the next generation, we cannot stop. The amendment of the Child Welfare Act is one huge step for their future.