From defending civil rights in the US to defending Central American revolutions from the US. From representing HIV-positive Haitian asylum seekers quarantined at Guantanamo Bay in the early 1990s to representing the Muslims brought there 10 years later in the “global war on terror.” From suing foreigners for torture in US courts to suing Americans for torture in courts abroad. The radical lawyer Michael Ratner, who died on May 11 at age 72, was always, instinctively, in the right place, fighting the right battle, from the right trench.

I first met Michael in June 1984. I had just returned from Nicaragua where, in a little hamlet by the Honduran border, villagers told me about the US-backed Contra rebels burning schools and farms and savagely murdering teachers and activists. I felt an enormous responsibility to do something -- indeed I promised the villagers that I would, but I didn’t know what to do.

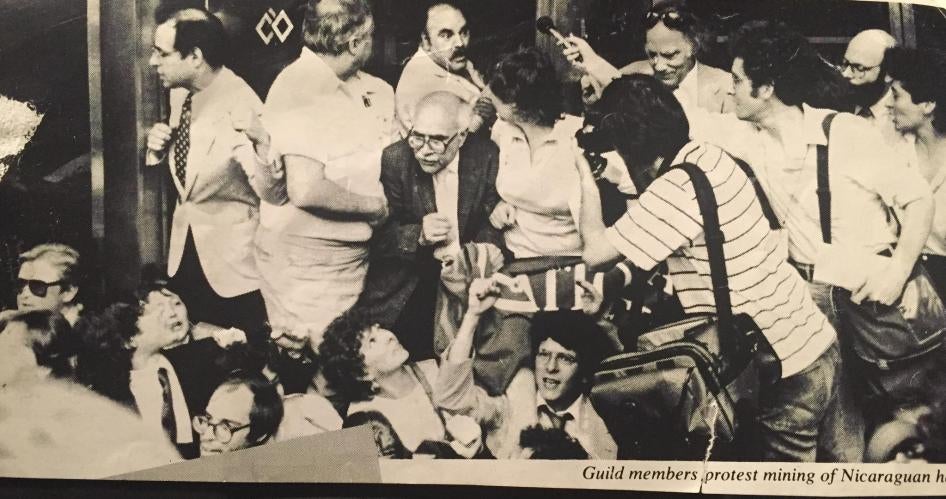

A few days after my return, the National Lawyers Guild organized a blockade of the Federal Building in lower Manhattan to protest US policy in Nicaragua. Michael was there with other luminaries such as Prof. Arthur Kinoy and activist lawyer Bill Kunstler. Although I had sworn that I wouldn’t do anything stupid for at least a week after my return, I was arrested that sweltering day with Michael and the others. That was my introduction to this man who was even then a reference on the progressive legal community, and I talked to him about how to fulfill my promise to the Nicaraguan villagers.

Out of our discussions grew the idea for what would become my five-month investigation of widespread Contra atrocities, which landed on the front page of the New York Times, helped change the terms of the debate, and led to a temporary cutoff of US aid to the Contras.

The next year, the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which used my report, ordered the US to stop supporting the Contras. Michael and the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), which he led for three decades, decided that the world court’s ruling had to be taken seriously and prepared to go to federal court to seek an injunction against further Contra aid. Feeling that they needed American plaintiffs with legal standing who could argue that their lives were at risk, Michael sent me back to Nicaragua, where I took statements from those who seemed the most exposed.

One of them was Ben Linder, whose daily work bringing electricity to remote villages put him directly in the Contra’s path. Ben signed an affidavit saying that he was “subject to personal danger to life and limb” and that if the court did not grant the injunction, he could “suffer irreparable physical harm as a result of the unlawful actions of the US government.” The federal court refused to grant the injunction and less than a year later Ben was the first and only American executed by the Contras. Michael then spent years representing the Linder family as they sought redress against Contra leaders and the US government.

Working together on issues ranging from Haiti to Abu Ghraib, Michael would become my best friend and mentor, my co-author (of The Pinochet Papers), my co-counsel, and for four years my Columbia Law School co-professor as we shared with a new generation of law students our ideas for how to “bring the bad guys to justice.”

Michael will perhaps best be remembered as the first member of the “Guantanamo Bar Association.” In early 2002, as the attack on the World Trade Center was fresh in the minds of Americans, the US began taking detainees captured in Afghanistan and elsewhere – whom Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld called “the worst of the worst” -- to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in an attempt to put them beyond the jurisdiction of the US courts. Michael and the CCR sued President George W. Bush on their behalf. Ultimately the US Supreme Court ruled that prisoners at Guantanamo had constitutional rights, which could be enforced by the US courts.

Most important, Michael was a gentle and generous human being who touched and inspired so many others all over the world. He and his wonderful wife, Karen, were – and are – at the heart of a large multi-generational progressive community in New York.

In announcing his death, the CCR said, “Today we mourn. Tomorrow we carry on his work.” Michael wouldn’t have it any other way.