(Goma) – At least 175 people have been kidnapped for ransom during 2015 in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Human Rights Watch said today. Former and current members of armed groups appear responsible for many of the kidnappings.

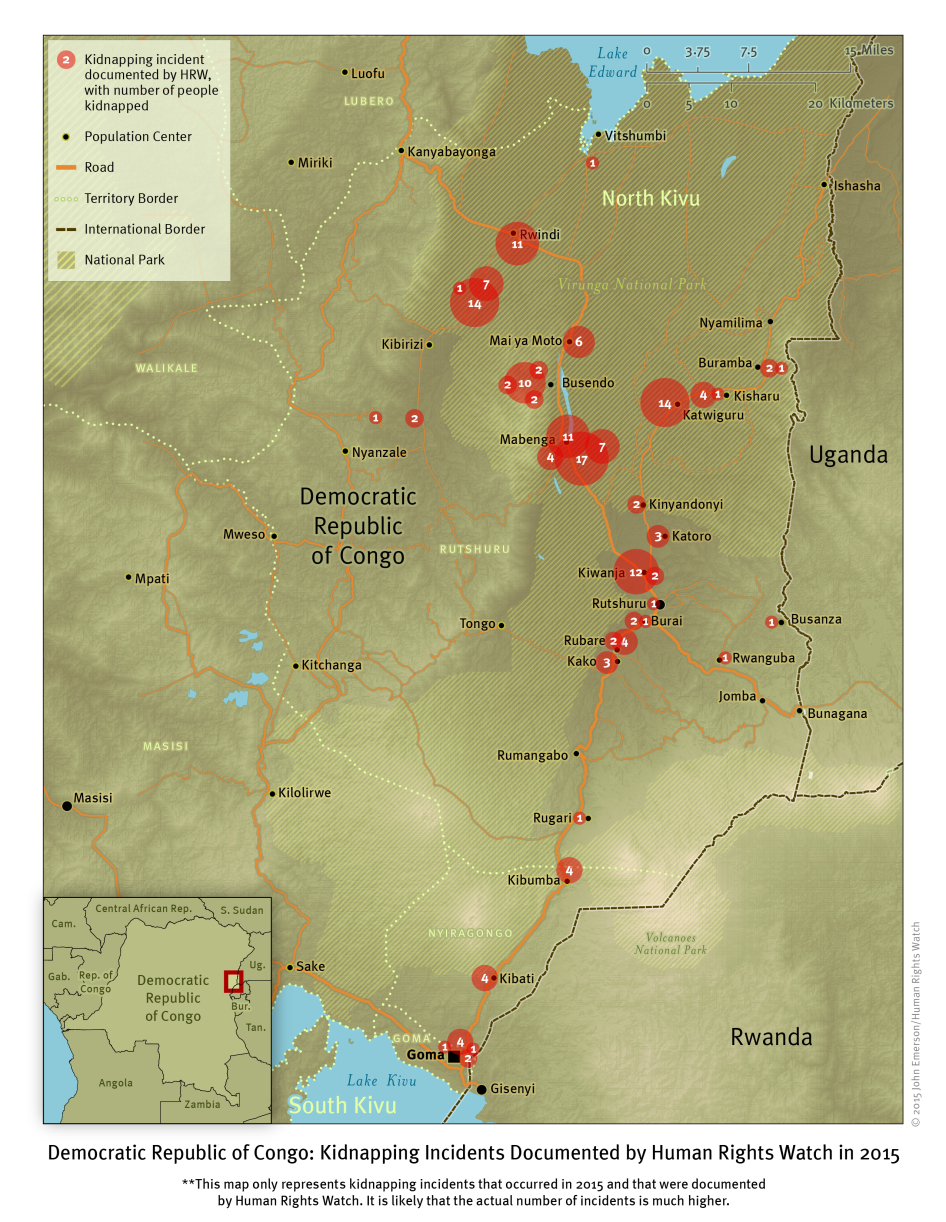

The vast majority of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch were in Rutshuru territory, North Kivu province, in the eastern part of the country. At least three hostages were killed while another was fatally shot in a kidnapping attempt. One remains missing. Nearly all hostages were released after relatives or employers paid ransom. Twenty of the victims were Congolese and international aid workers.

“The alarming increase in kidnappings is a grave threat to the people of eastern Congo,” said Ida Sawyer, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Congolese authorities should urgently establish a special police unit to help rescue hostages and investigate and prosecute those responsible.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed 45 former hostages and witnesses in North Kivu between May and December. They said that the kidnappers typically operate in groups of up to a dozen or more people, and are often heavily armed with Kalashnikovs and other military assault weapons. Many wear military clothes and appear to belong, or to have belonged, to one of the many armed groups active in eastern Congo.

The kidnappers often followed a similar procedure, beating, whipping, or threatening their hostages with death, demanding that they call their relatives or employers to press them to pay for the person’s release. The kidnappers often used the victims’ cell phones or their own to negotiate the ransom payments. Sometimes the kidnappers abducted a single hostage, in other cases, a group.

In one example, on September 2, armed men kidnapped a 27-year-old student near the general hospital in Goma and took her to a remote forest location, where she was held with other hostages. The kidnappers beat and abused the hostages, including burning them with bayonets heated in a fire. “When we asked for food, they chose a man among us and cut his throat, killing him,” she told Human Rights Watch. “‘If you want to eat, here’s the meat,’ they told us.” She was held for nine days, and released after her family paid a ransom.

In the cases Human Rights Watch documented, kidnappers demanded between US$200 and US$30,000 per hostage, though the amounts paid were often much lower than the amount sought, according to relatives and former hostages.

The ransom payments often caused severe financial hardship for families. One man had to sell his farmland to pay off the money his family had borrowed to pay for his release, leaving his family with no source of income.

Kidnappers also targeted national and international aid workers, contract staff working for the United Nations, and drivers for a major transportation company. In all cases they were later released. No information was made public on whether ransoms were paid.

In most of the cases Human Rights Watch documented, relatives of the hostages did not inform police or other authorities about the kidnapping, either because they believed they would get no assistance or because they feared that it might make matters worse and that they would face further extortion from the authorities for any assistance provided. One former hostage said that when her mother told a judicial official in Goma that her daughter had been kidnapped, his only response was that the mother should “go pay.”

At least 14 people were kidnapped close to areas where Congolese soldiers were based, leading some of the victims and their families to speculate that the soldiers may have been complicit. Human Rights Watch found no credible evidence indicating that Congolese soldiers participated in the kidnappings, though some of those involved appear to be members or former members of armed groups that Congolese army officers had armed or supported in the past.

One of the implicated groups is the Force for the Defense of the Interests of Congolese People (FDIPC), which collaborated with the Congolese army during military operations against the M23 rebel group in 2012 and 2013, according to Human Rights Watch and UN research. Former hostages and local authorities told Human Rights Watch that FDIPC fighters and former fighters were responsible for some of the kidnappings.

On April 14, 2015, Congolese authorities arrested FDIPC’s military commander, Jean Emmanuel Biriko (known as Manoti), his wife, and a dozen of his fighters and charged them with kidnapping, among other crimes. Their trial began a day later in a military court in the town of Rutshuru. On May 18, following deeply flawed proceedings in which the rights of the accused were violated, the court convicted Manoti and 10 of his co-accused and sentenced them to death for belonging to a criminal gang. Although the death penalty is still permitted in Congo, there has been a moratorium on executions since 2003. Human Rights Watch opposes the death penalty in all circumstances as an inhumane and irrevocable punishment.

During the trial, Manoti alleged that he collaborated with several Congolese army officers, including one he said was involved in the kidnapping incidents. Human Rights Watch has not been able to identify any judicial investigations into the alleged role played by these or other army officers, although government and military officials know of these allegations. A high-ranking army intelligence officer acknowledged to Human Rights Watch that Manoti “might have worked with some of the military” during the kidnapping incidents.

The arrest of Manoti and his men did not end the kidnappings. The majority of cases Human Rights Watch documented in 2015 occurred after their arrest. While Congolese authorities say they have arrested other alleged kidnappers, none have been brought to trial.

Citing the “immeasurable scale” of kidnappings in eastern Congo, the National Assembly’s Defense and Security Commission held a hearing on December 3 with the Vice Prime Minister and Interior Minister Evariste Boshab about the government’s response. Boshab replied that the situation is “extremely worrying” and “among the biggest security challenges confronting the government today.”

Three commission members said it was agreed that a parliamentary commission of inquiry would be established to investigate the kidnappings and possible complicity by government and security officials, and to assess what has already been done and make recommendations.

Human Rights Watch urged the commission to endorse the creation of a special police unit to document and respond to kidnapping cases; identify and arrest alleged kidnappers; report alleged complicity between kidnappers and officials; and work with judicial officers to bring those found responsible to justice in fair and credible trials.

“Putting an end to the kidnapping threat should be a top priority for the Congolese government,” Sawyer said. “The authorities not only need to bring those responsible to justice in fair trials, but also to uncover and act against any officials involved.”

For additional information and accounts from former hostages, please see below.

The Kidnappings

Human Rights Watch confirmed the kidnapping for ransom of 172 Congolese and three foreign nationals in 35 separate incidents in Rutshuru, two in Nyirangongo, one in Walikale, and four in Goma, in 2015. The actual number of cases is likely much higher. Human Rights Watch also received reports of kidnapping cases in Butembo town and Beni territory in 2015, but they are beyond the scope of this research.

Most of the kidnappings Human Rights Watch documented were in areas previously controlled by the M23, a Rwandan-backed rebellion that was responsible for widespread war crimes between early 2012 and late 2013, when Congolese military and UN forces defeated the group. A new national disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) program to disarm former combatants from the M23 and other armed groups and provide them with other economic opportunities has yet to become fully operational. Fighters who surrendered from various armed groups in the past two years have been sent to regroupment camps, where they have waited for months, often in abysmal conditions, for the program to begin. Some abandoned the camps, tired of waiting, and went back to their armed groups or turned to other criminal activity, including kidnapping.

Many kidnappings occurred on major roads in Rutshuru and Nyiragongo territories, North Kivu, including the roads from Rutshuru to Rwindi, Nyiragongo to Rutshuru, Rutshuru to Nyamilima, Rwindi to Nyanzale, and Rutshuru to Bunagana.

Human Rights Watch found that victims were not singled out on the basis of their ethnicity. The vast majority were men. If women were captured, they were often robbed and immediately released. Human Rights Watch documented five cases of women being taken as hostages. Victims ranged in age from 4 to 70. Kidnappers targeted people on roads, in farms, in homes, and at school. They were held for between eight hours and nine days.

The Human Rights Watch findings are based on three research missions to Kibirizi and Kiwanja, Rutshuru territory, and interviews in person and over the phone in Goma. Altogether, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 70 former hostages, witnesses, rights activists, businessmen, local and customary authorities, government officials, police and military intelligence officers, and civilian staff of the UN peacekeeping mission.

Accounts From Former Hostages

A 19-year-old woman kidnapped in Goma on September 18 after she accepted a ride from three men:

Another girl was also in the car when I got in. When we realized that they were taking us in the wrong direction, we started to scream. The driver then climbed over and put Scotch tape over my mouth and eyes. He also taped the other girl. They bound my feet and hands with a belt. I didn’t know where I was or where we were going. A little later, I heard the car honk and two men carried me into a house. Later that day, they injected me with something, and I lost consciousness.

She was released nine days later, after her family paid $300 to the kidnappers. After seeing a doctor, she learned she had been raped while unconscious.

A 27-year-old female student was kidnapped at 11 a.m. on September 2, near the general hospital in Goma:

I was on my way to the university when a car honked at me from behind. One of the passengers called me by my father’s last name. They told me they had tried to reach my brother by phone to give him a package but he didn’t pick up. They asked me to come with them to pick it up. I had the courage to get into the car because they knew my father. I didn’t know any of them. When we passed by the Karibu Hotel, I lost consciousness. I don’t know how. The next day, I found myself in a forest. There I met other people who had been kidnapped: children, men, and women. We were all beaten. They put a bayonet in the fire and then held it over our bellies. It was horribly painful. One day, when we asked for food, they chose a man among us and cut his throat, killing him. “If you want to eat, here’s the meat,” they told us. My family sent $7,000 via Airtel Money. I don’t know what happened next but when I woke up I found myself outside [the town of] Sake.

A group of nearby women helped her find a telephone to call her family and return to Goma nine days after her capture. She is being treated by a psychologist for the after-effects of the experience.

An ethnic Shi man, 48, was kidnapped with six others on the Rwindi-Kibirizi road, Rutshuru territory, in July:

Three armed men were waiting for us in the park…They put up a rope across the road to make us stop. It was frightening. Some of us urinated on ourselves. We didn’t know which saint might save us. They systematically looted the vehicle and each of us had to give up his cell phone and all the money we possessed. Shortly thereafter, they gave us an order to start walking. In the forest we met another 11 men who were hiding. All had firearms. We walked for a very long time until we set up camp deep in the forest [of Virunga National Park].

The next day, their chief told us: “We can do with you whatever we want. We are alone with you. We can even cut off your head and make you the food of the animals in the park. We can keep you here for six months and nobody will be able to do anything for you. We know that you don’t have money with you here but your families do. So, we are going to give you your [cell] phones.” And so each of us was given our phones back to find one or two numbers for our relatives. “You are going to tell them that you are in the park with the lions and that they have to each bring $1,000 for your liberation. This is urgent. It isn’t negotiable,” [the kidnapper said].

The victim was released three days later after relatives paid $1,000.

A businessman, 53, kidnapped with 16 other men on May 17, in Mabenga, Rutshuru territory:

We were in a public bus toward Mabenga when we encountered bandits who started to shoot in the air and then at our tires. One of the passengers was immediately killed … another person was injured. I wanted to flee but a bandit said: “To those who dare to flee, we will kill you in the same way.” … The women who were with us in the bus were not taken. We were only men, 17 of us.

When the FARDC [Congolese army] learned about our kidnapping, they came to help. They fired a lot of shots at the kidnappers. One of the bandits said: “Your military wants to free you, we’re going to show you who we are.” Immediately they shot one of [the hostages], who then died in the fields.

The passengers were later released, one after another, for ransoms ranging from $500 to $4,000. Together with his nephew, the businessman was released after nine days and a $1,000 payment.

A 31-year-old man, whose family paid $1,500 after he had been kidnapped in Mabenga, Rutshuru territory, and held for two days in mid-May:

At the moment, my family is in total misery. We no longer have money … I lost my job after the kidnapping. I don’t know why. So, I am now an unemployed man at home.

An ethnic Hunde bus driver, 40, kidnapped by four assailants on May 12, in Rugari, Rutshuru territory:

I was in the car just past Rugari when four armed men appeared in front of us. They started to shoot at us. One of the passengers was hit in the arm. I immediately stopped the bus. They only took me. They took me into the forest.… They blindfolded me and told me: “We could have taken you yesterday when you returned from Rutshuru but you were with a delegation of politicians. This morning when you left the parking lot in Goma, our scouts informed us that you were on the road. Now, we have you, and you are in our hands. Our objective is to kill you. If you don’t want us to put an end to your life, you have to give us $10,000.”

His family left $2,000 in a jacket hanging from a tree two days later as ransom, securing his release. He later lost his job because his employer no longer trusted him after the incident.

A teacher, 62, was kidnapped from his home in Bukoma, Rutshuru territory, on May 9:

It was 8 p.m. and I was eating with my family when three armed men entered my home, calling me by my name. Threatened at gunpoint and with my children trembling, I gave them all the money I had in the house. They weren’t satisfied with this, though, so they took me hostage and demanded a ransom for my release.

He was released a day later after his colleagues urgently collected another $1,500 to pay the kidnappers.

A 24-year-old vendor of mobile phone credit kidnapped on May 5, near Rwindi, Rutshuru territory:

After we passed Rwindi, a man in a military uniform appeared at the side of the road and started to shoot in the air. The bus driver stopped immediately and we realized that we were surrounded by nine other bandits. They also wore military uniforms and started to shoot in the air. One could have believed this was a war.

The bandits forced us to follow them into the forest. Nobody tried to resist. We were 14 men. They didn’t take any of the women. They only robbed them and told them to stay with the bus. In the forest they started to beat us. They whipped us heavily. We couldn’t do anything other than cry. Nobody could have come to help us in the forest.…

I can’t imagine the number of lashes I received. After they whipped us, they told us in Swahili: “We want to kill you now.” They asked the second [bus] driver: “Do you have any money left?” He told them that he had nothing. Immediately, they put a knife to his throat saying: “We kill you now.” He cried loudly and begged them for mercy. By the grace of God, he wasn’t killed. Then they turned to me asking for money. I was lying on the ground and had a machete at my neck. I prayed. “Dear Lord, receive my soul!” They let go of me, but I was whipped again until I had nothing left in me.

He and the other 13 men were released after three days in captivity when their families made ransom payments.

A bus driver was attacked with 18 of his passengers and his assistant on May 4, in Rutshuru territory:

We were two kilometers outside Burai when we passed an army position. About 150 meters ahead of us was another one of their positions. Suddenly, I saw an unarmed man in a rain poncho. He made gestures for me to stop and walked into the middle of the road. I began to slow down. Then, on my left, an armed man in civilian clothes shot at a tire of my bus. My assistant and the passengers immediately started to get off the bus. Meanwhile, another two assailants arrived and together they pulled me out of the vehicle. They pillaged the bus and all the passengers. They took me alone into the forest.

The driver was set free three days later after a ransom payment of $1,200.

A 45-year-old bus driver kidnapped with one of his passengers in May, in Busendu, Rutshuru territory:

The bandits arrested us and confiscated our cell phones. We were 500 meters away from an FARDC position and where [Virunga] park rangers were posted. They only shot in the air, but they didn’t come to help us. One of the [two] assailants also shot in the air while the other bandit led us into the forest.

The two hostages were released two days later for a ransom payment of $3,000.

A father of a 17-year-old cow herder in Bwito, Rutshuru territory, who was kidnapped and later killed by alleged fighters from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a largely Rwandan Hutu armed group active in eastern Congo:

Early in the morning on April 2, I asked my son to go to the pasture lands to bring salt and medicine for the cows to the herdsmen. [Later that day] an FDLR fighter called me and passed the phone to my son. “Papa, I am with the FDLR,” he said. “They are asking for $3,000.” Before my son could continue, they took the phone away from him. “We don’t have enough time to discuss this with you. If the money doesn’t get here before 3 p.m., we’re going to leave you only the corpse of your son.” A little later, three hours I believe, they called again. “You have less than two hours to react.” Later they called me yet again saying that they were being pursued by the FARDC. “We need to move.” Then, they explained where to bring the money to. When I arrived there, I saw the body of my son, abandoned, with his head cut off. I didn’t know what to do. I cried … I buried my son the next morning.

A 51-year-old farmer was kidnapped together with three UN contractors on April 23, in the Virunga National Park, Rutshuru territory:

I was cutting firewood when two men came behind me. “If you flee, we are going to kill you.” They were both armed and in civilian clothes. They made me walk. After a few meters, I found another three men abducted. They were guarded by four men. The men asked me to sit down. In the evening, they asked us to get up and start walking again. In Gishanga, we met another group of armed men. There were dozens of them. The kidnappers carried six boxes of ammunition. These men were not FDLR because they were majority Tutsi [members of an ethnic group unlikely to join the largely Hutu FDLR]. They knew where FDLR had their positions and so we could avoid them and go to Kalengera, Tongo and finally to Burungu.

On Saturday, April 25, they let us go after the family of the three men had paid money for our release. One of their family members had been told to send money to a bank account in Gisenyi in Rwanda. It was me who led the [three] men back to Kibumba. The kidnappers gave me a machete to cut a trail in the forest.

A 52-year-old father of 10 kidnapped for three days in Busendo, Rutshuru territory, in April:

I had to work immediately to find money to pay back my debt. I don’t know how to do it. I have many problems. I was forced to sell my field to make $200. The situation in Binza [Rutshuru territory] is really bad. We no longer stay at home but in our fields. There’s no security. We are stuck.