Despite the chilly morning air in Berlin, Dr. Sami Sharif prefers to sit at one of the café’s outside tables, where he can smoke. He sips his espresso and smiles, as he tells me that when he was younger, he didn’t want to be a doctor at all, he wanted to study physics. But in 2011, when he was in his 5th year of medical school and training in Damascus hospitals, the uprising began in Syria. “When I realized I could help people, I loved being a doctor.”

He and his friends formed a secret group of doctors who treated wounded protesters, something that could lead to their arrest under President Bashar al-Assad’s government. They stashed bags with medications and surgical equipment in houses around Damascus, and in 2012 they set up clandestine field hospitals in Damascus and north of Homs.

Sami, 27, has a neatly trimmed beard and wears a heavy winter coat, a gift from his Germany host family. When our conversation got tough for him, he’d bunch his hands into the pockets. Although he knew his work was dangerous, he somehow felt invincible, he says. He never thought he’d be detained and tortured, or that at the urging of his family – he grew up in Qamishli, in a Kurdish area of Syria – he’d flee his home for Germany.

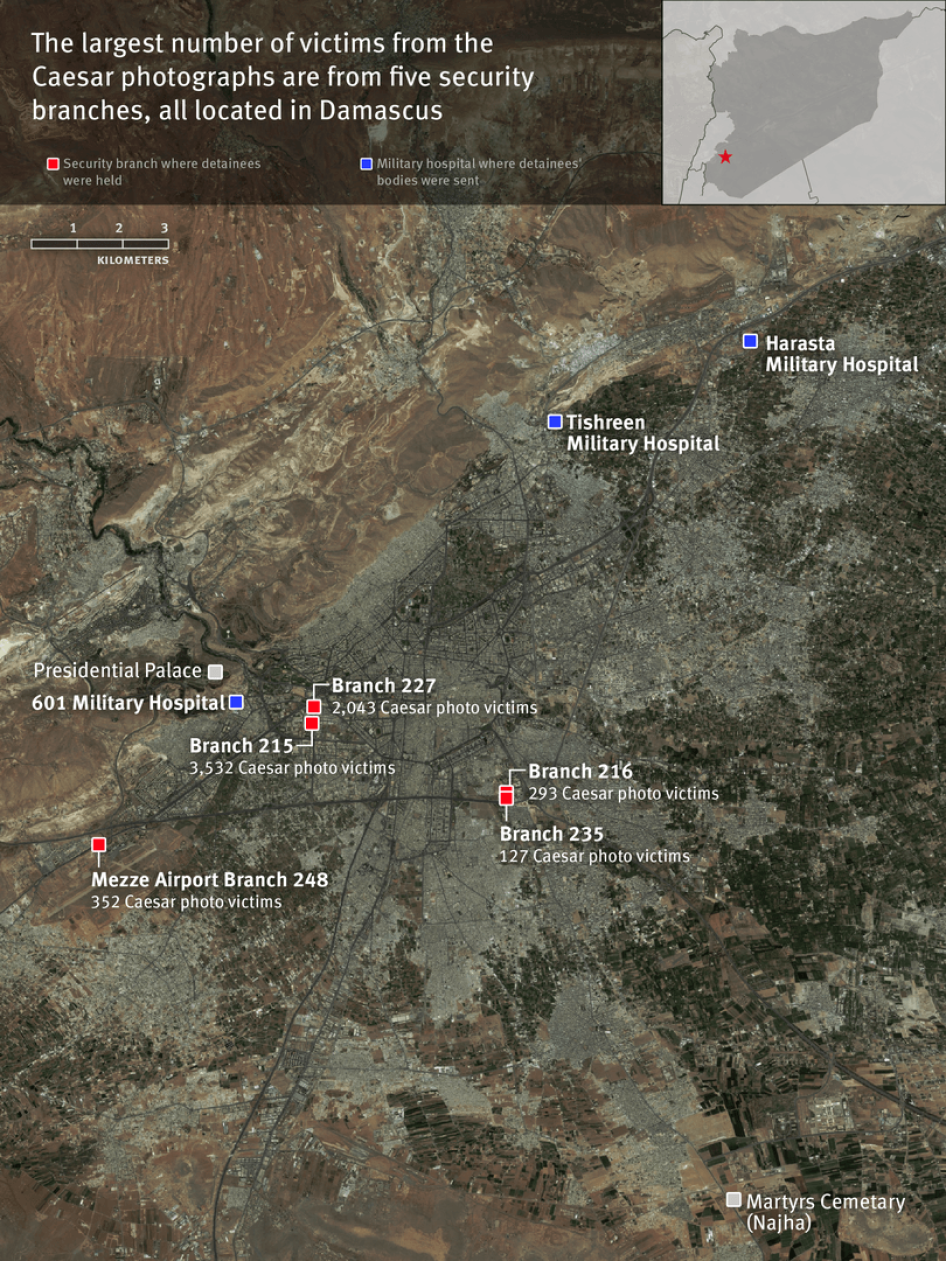

A new Human Rights Watch report contains an in-depth examination of the photos of dead detainees in Syria, taken by a Military Police photographer referred to as “Caesar,” who had more than 28,000 images documenting 6,786 dead when he fled Syria. Human Rights Watch uncovered many of the dead’s names, interviewed their friends and family, as well as former detainees and medical professionals, to establish possible causes of death. The bodies of seven of Sami’s friends were among the Caesar photographs, he said.

As the fighting in Syria continued, Sami became increasingly attuned to the dangers he faced. He fled Damascus once on fear of being detained, returning only when he learned he wasn’t officially “wanted.” He stopped working in make-shift field hospitals – “it was too dangerous,” he says – and instead in 2013 worked to finish his hospital residency in Damascus, where he often treated civilians injured by rebel bombs. He didn’t trust his colleagues.

Then, in September 2014, Syrian security forces – the feared mukhabarat - detained his girlfriend, Nada, who he met earlier doing covert medical work. One day, he called her to say good morning, but there was no answer. He called again - no answer. And again. Then her sister called him, crying. “She said the security forces went to her office and took her.”

A secret service agent called him, and said that if he turned himself in, Nada would be fine, they’d let her go. They told him to meet them on a busy street in Damascus. “I didn’t want them to torture her,” he said.

He went to the meeting point, and a black car with darkened windows pulled up. A big man opened up the driver’s door, got out, said, “Hello, you can come with us,” and pushed him into the backseat. Someone else pulled his t-shirt over his head to blindfold him, but not before he saw Nada’s phone on the seat. The insults and hitting soon started.

They drove him to a building, took his money, IDs, and fingerprints, and kept him blindfolded. They stood him on his knees. “I could smell blood and hear people being beaten.” Dr. Sami says, his voice cracking. He paused and took a deep breath. “Sometimes that’s the hardest.”

They held him in one of the detention facilities of the mukhabarat. “I was there for about a month,” he says crossing his arms over his chest and bowing slightly forward, as if he were protecting himself.

The cell was one large room, crowded with about 300 detainees. They took turns sitting down. Each day, the men received ½ of a raw potato and 2 to 3 spoonfuls of uncooked bulgur wheat, he said. As a doctor, he could diagnose what he saw around him – scabies and impetigo, a contagious skin infection, were rampant. Prisoners with high blood pressure and diabetes didn’t receive medication. “Diarrhea was the number one killer in the prison,” he says “Every prisoner who got diarrhea, in three, four or five days they were dead.”

“I was tortured,” he says. “I was beaten with a solid plastic hose … I was hung by my hands,” he says, noting that this can destroy the radial nerve in the wrist, making wrists permanently limp. He recognized the signs of torture in others based on their injuries. Some people’s hands were tied behind their back before they were tied to a ladder. When the ladder bends open or closed, it destroys the nerves in prisoner’s shoulders. Afterwards, the only movement they could make with their shoulders was flap their arms like birds. He saw prisoners that were electrocuted, and one whose spine was broken by torture.

Some prisoners would lose hope, Sami said, stopping eating and using the toilet, muttering to themselves. He found it hard to sleep due to the ever-present sounds of torture and screaming. In the cells, people died daily, Sami said. Sometimes jailors would leave a body in his cell for a while.

People in the cell would ask him for help, knowing he was a doctor, Sami says. He stopped talking, burrowed his chin into his chest and squeezed his eyes closed tight, pinching the bridge of his nose. “They came to me, saying they needed help. They said you are a doctor. But I couldn’t do anything. I could only say if people were alive or they’re dead.”

As far as being detained goes, “I was the best case scenario,” Sami says. “People knew who took me and essentially where I was being taken. The most terrible thing is if they don’t know where you are.” His family and friends worked their connections to get him out, and ultimately, someone knew someone who arranged for money to be paid to the right person.

They released him to the central prison in Adraa – where he wasn’t tortured and where he received food. One month and 10 days later, he was released to the outside world. Sami was very thin, and had scabies and bronchitis. He had a hard time bending his right knee.

He stayed with his family for one month. “It was terrible for them,” he said. “Every day when the doorbell rang, they were so worried.” His family wanted him to flee, and he left for Turkey, where he spent seven months. His family urged him to go to Germany, where he could continue his studies. His brother – Sami is the youngest of 11 children – scraped together money for the trip. “They are happy I’m in Berlin. ‘You are far, but you are safe,’ they say."

Sami has now lived in Berlin for a few months. Most days, he volunteers in a refugee center’s emergency health clinic, translating medical information from Arabic or Kurdish to English. He’s taking German classes, and hopes to bring Nada over.

He also wants to continue his studies. But instead of continuing to work as a surgeon, he wants to be a psychiatrist. He talks about his struggle with depression; he knows he’s not alone in this. “So many kids saw so much blood. Then there’s the detainees, the people who experienced war,” he says. “There will be so many mental disorders.” He wants to move back to Syria after the war.

We leave the café and walk up the street to the refugee center, passing all types of people on the sidewalk. “I love Berlin. Look at this city. It was once destroyed in a war. It was divided in half. And now, look at the people, it is so lively. Maybe Syria can be like Berlin.”