Samir is chatty and smart. Little of the 11-year-old’s confident demeanor reveals the horrors he has seen. Sitting bolt upright in one of his family’s two armchairs, the young Syrian politely answers questions, eager to share his story of uprooting and his life as a refugee in Izmir, a bustling town on Turkey’s Aegean coast. Unperturbed by the honking cars and yelling children near his family’s rental apartment, he told Human Rights Watch researcher Stephanie Gee about the life he left behind, and the country that has become his refuge, but not his home.

Samir was about to finish grade 2 when his school in Aleppo was shelled. His father, Haysam, a 35-year-old shoemaker, badly wanted Samir to get an education, but given the circumstances, decided it was safer to keep him home. That was during the summer of 2012, when fighters opposed to the government– many based in the northern countryside– opened an offensive for control over Aleppo, and opposition-controlled parts of the city came increasingly under attack by government forces. Helicopters, fighter jets and tanks were shelling and bombing populated areas, hitting bread lines, the city’s main emergency hospital and schools. Every day, scores of people died or were injured.

When the situation hadn’t improved by early 2013, Haysam locked up his shoe shop and moved his family first to Lebanon, then to Turkey – which has welcomed more than 2 million Syrian refugees, more than any other country. He hoped to find safe shelter, work for himself, and schools for his two sons.

More than two and a half years later, however, Samir is still out of school.

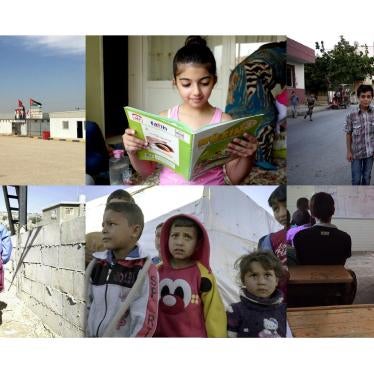

He is not alone in missing out on an education. Of the 700,000 Syrian school-age children who have entered Turkey in the last four years, fewer than one-third are attending school. Nine out of 10 in government-run refugee camps are enrolled in classes. But nearly 90 percent of Syrian refugees, like Samir, live outside the 25 crowded camps, and the majority of their children are not in school.

Turkish officials have voiced concern over the number of youngsters out of school. “If we cannot educate these students, they will fall into the wrong hands, they are going to be exploited by gangs, criminals,” Turkey’s deputy undersecretary for education, Yusuf Buyuk, warned recently. To make access to education easier for refugee children, the Turkish government has lowered some bureaucratic hurdles for public school registration. Now a foreign identification permit, issued by Turkish authorities, suffices to enroll a refugee child in school, increasing admission numbers considerably.

Yet, as a new Human Rights Watch report, “When I Picture My Future, I See Nothing,” documents, language hurdles, misinformation about the procedures for enrolling children, and financial concerns keep most refugee children from formal education. With Syrian refugees unable to obtain work permits, many cannot afford private schools and feel compelled to put their children to work in Turkey’s grey economy..

As it is often easier for adolescents than for adults to find work in Turkey because children are cheaper to employ, a great number of refugee families rely on their offspring to supplement their household income. As a result, the Syrian refugee influx has created a spike in child labor throughout the country. Syrian children interviewed for the report worked in garment factories, dried fruit factories, shoemaking workshops, and auto mechanic shops. Some picked cherries or worked as agricultural laborers, while others sold tissues, water, or dates on the street. Some were the family’s primary breadwinners.

Despite escaping death and destruction, Samir and his peers are in danger of ending up as Syria’s lost generation. That is a tragic development considering that prior to the conflict, Syria had achieved virtually universal education for girls and boys alike.

Today, nearly three million Syrian children inside and outside the country are out of school, Unicef estimates. Yet, education matters to Syria’s refugee parents. The desire to give their children a chance at formal schooling and possibly college is, according to Unicef, one of seven key reasons why many leave everything behind in war-torn Syria and put their fate in the hands of smugglers. Finding a school for his sons was foremost on Haysam’s mind once he made it to Turkey.

By the time the family had settled in their one-bedroom apartment, Samir had already missed almost two years of school. When his father tried to register him for the 2014 spring semester, the school administration rejected him because he didn’t have a residency permit, a requirement at the time. That fall, a change in policy meant the then 10-year-old was finally accepted at a public school, but forced to enrol in grade 5 – three grades above the one he had almost completed.

“We requested from the school that they place him in a lower level, but they refused,” Haysam said. “According to his size and age, they said it was impossible. We tried to explain how hard the language is for Arabs, but they said no. They weren’t interested in helping.” A week later, Samir had dropped out of school for good.

"He is smart, and he was a good student,” Haysam said, recalling the high hopes he once had for his firstborn.

“Come on,” retorted Samir with a wry smile, teasing his father, “I never really liked studying.” But this quip seemed as much a means for Samir to cope with his new life as his way of soothing his dad.

Samir said he found it hard to follow the lessons in Turkish. But what really hurt him was the way his fellow students treated him. “The other kids were cursing me and teasing me,” he told Gee. “I couldn’t understand exactly what they were saying, but I knew from the way they said it and the way they treated me, that it wasn’t nice. I felt very upset and isolated.”

Language barriers and bullying, the report found, are key reasons for refugee kids like Samir to drop out of school. Yet schools offer little support for children who speak little or no Turkish, and teachers lack training to ensure that pupils who fled violence in Syria do not end up traumatized by their classmates.

Samir, following in his father’s footsteps, now cuts leather in a shoemaking shop. Side by side, the two work from dawn to dusk, six days a week, without health insurance or labor protection. What they take home is just enough to cover the family’s basic living costs. “Of course I wish Samir could have finished high school before he started work,”Haysam said. “But working in a workshop is better than being in the street. At least he is learning a trade. And I can watch out for him.”

Roughly 1,000 kilometers east, 15-year-old Ibrahim has no father to watch over him. The teenager left Aleppo with his mother and two brothers for the relative safety of the countryside in early 2014, after government forces dropped a barrel bomb filled with explosives and nails 25 meters from the family’s pharmacy. Then Islamic State (also known as ISIS) took over the area the family had escaped to. They fled to Turkey.

They now live in a one-bedroom apartment in Mersin, on Turkey’s coast. Ibrahim’s elder brother Omar, 27, has taken over the role of caretaker and breadwinner. An interior decorator by profession, without a work permit Omar has to accept badly paid piecemeal work. He doesn’t believe that sending his younger siblings to a school where only Turkish is spoken would benefit them — especially when money is so tight – yet he can,t afford to enrol his brothers in an alternative private school, a so-called temporary education center, that teaches a Syrian curriculum in Arabic.

Ibrahim, who should be in grade 9, has found work painting cars, and his younger brother Ahmed, 13, works as a tailor. The hours are long, and sometimes Ibrahim works Sundays, too. His legs ache and his chest feels tight from breathing in the toxic paint fumes. Even if he had friends, he wouldn’t have time for them, he said.

“I really, really, really miss school,” Ibrahim said. When he talked about his favorite subject, math, his face lit up in a rare smile. “I loved studying math,” he declared with visible enthusiasm. “But here I don’t have any books or anything I can use to study on my own.”

Having fled aerial bombardments by their own government and attacks by armed groups and extremists in the hope of rebuilding their shattered lives, Ibrahim and his brothers no longer believe Turkey holds any future for them. “God willing in a month or so from now, when there is no ISIS around, we will go back to Syria”, said Omar, “and my brothers can attend school there.”

Omar and his brothers would not be the first young men to return. Yet not all who return do so to resume their studies. Some, frustrated and angry, have gone back to fight the very war they fled. At least one will never be back.

Forced to abandon his education and with no chance of a lawful job, the 16-year-old son of a well-known female Syrian activist returned to Syria to join the fight against the Assad government. He was killed in battle shortly thereafter.

But providing an education to young Syrian refugees such as Samir and Ibrahim will not only reduce the risk of military recruitment and radicalization. Education is crucial to equip Syria’s future generation with the skills needed to rebuild their country. None should feel pushed to forsake their lives on the battlefield out of despair at having been deprived of this fundamental right -- to get an education.