Summary

If a person is sick, they can get treatment and get better. If a child doesn’t go to school, it will create big problems in the future—they will end up on the streets, or go back to Syria to die fighting, or be radicalized into extremists, or die in the ocean trying to reach Europe.

—Shaza Barakat, founder of a Syrian temporary education center in Istanbul and mother to a son who died at age 16 in 2012, when he returned to Syria to fight with opposition forces after finding no educational opportunities in Turkey

Now that I can’t go to school, it’s a tough situation. It’s hard to get used to it. I work occasionally, filling in for my sisters at the factory. When I picture my future, I see nothing.

—Rasha, 16, who was unable to enroll in school when she arrived in Izmir, Turkey, from Qamishli, Syria in August 2013, because she lacked a residency permit. Unable to speak Turkish, she could not join her peers in the 10th grade, and was not allowed to join a lower grade.

Nine-year-old Mohammed has not attended school since 2012, when an armed group took over his school in the Aleppo countryside. His family, which fled to the Turkish seaside city of Mersin in early 2015, now lives in a small, unfurnished apartment and sleeps on the floor.

Mohammed, who would now be in third grade, misses going to school. “I was one of the best in my class, and I really liked learning how to read. But now we don’t even have any books or anything that I can use to study on my own.” He works eleven-hour daily shifts at a garment workshop where he earns 50 Turkish lira (approximately US$18) per week.

This report is the first of a three-part series addressing the urgent issue of access to education for Syrian refugee schoolchildren in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon. The series will examine the various barriers preventing Syrian children from accessing education and call on host governments, international donors, and implementing partners to mitigate their impact in order to prevent a lost generation of Syrian children.

Syrian Refugees in Turkey[1]

Prior to the conflict, the primary school enrollment rate in Syria was 99 percent and lower secondary school enrollment was 82 percent, with high gender parity. Today, nearly 3 million Syrian children inside and outside the country are out of school, according to UNICEF estimates—demolishing Syria’s achievement of near universal education before the war.

In Turkey’s 25 government-run refugee camps, approximately 90 percent of school-aged Syrian children regularly attend school. However, these children represent just 13 percent of the Syrian refugee school-aged population in Turkey. The vast majority of Syrian children in Turkey live outside refugee camps in towns and cities, where their school enrollment rate is much lower—in 2014-2015, only 25 percent of them attended school.

Some children in the 50 families that Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report had lost as many as four years of education, while others, too young for school when the war broke out in 2011, had never set foot in a school building. Many of them first suffered disruptions to their education when their schools in Syria were shelled or overtaken by armed groups. Upon arriving in Turkey, their education gap lengthened or became permanent. On average, the children we interviewed had lost two years of schooling.

Under international law, the government of Turkey is obligated to provide all children in Turkey with free and compulsory primary education and with access to secondary education.

Turkey has taken several positive steps to meet its obligations by lifting legal barriers to Syrian children’s access to formal education. In 2014, for example, the government lifted restrictions requiring Syrians to produce a Turkish residency permit in order to enroll in public schools, instead making the public school system available to all Syrian children with a government-issued ID. It also began to accredit a parallel system of “temporary education centers” that offer an Arabic-language curriculum approved by the education ministry of the Syrian Interim Government, a cabinet of Syrian opposition authorities in exile in Turkey.

However, for all its efforts, Turkey has not yet succeeded in making education available to most Syrian refugee children in Turkey, especially those living outside the camps, and the laudable progress to date should be considered only the beginning of efforts to scale-up enrollment.

Overall, less than one-third of the 700,000 Syrian school-aged children who entered Turkey in the last four years are attending school—meaning approximately 485,000 remain unable to access education.

Human Rights Watch research found that a number of addressable barriers prevent Syrian refugee children in Turkey who live outside refugee camps from attending school, above all:

- Language barriers: most Arabic-speaking Syrian children face a language barrier in Turkish-language schools.

- Economic hardship: lack of money affects families’ ability to pay the costs of transportation, supplies, and—in the case of temporary education centers— tuition. Child labor is rampant among the Syrian refugee population, to whom Turkey does not give work permits due to concerns about the effects on its host unemployed population. As a result, many families are dependent on their children’s income because parents cannot make a fair wage without labor protections.

- Social integration: Concerns about bullying and difficulties integrating with Turkish classmates prevent some Syrian families from enrolling their children in local public schools.

Moreover, this report finds that some Turkish schools have turned away refugee children or failed to reasonably accommodate their needs, and that temporary education centers are often overcrowded. Despite Turkey’s revised legal framework guaranteeing access to public schools for Syrian refugee children, some Syrian families told Human Rights Watch that Turkish public schools continued to demand they produce documents that are no longer required for enrollment. Furthermore, many families lack crucial information on Turkey’s school registration procedures.

For example, Mohammed’s mother told Human Rights Watch that he and his 11-year-old brother were not in school because “we don’t know anything about how to register or if they are allowed to go.” She explained that because her husband does not have a work permit, he works illegally in a garment factory for wages far below his Turkish co-workers. Her two sons work, she said, because her husband’s income does not adequately cover the family’s living expenses.

Turkey has already shouldered a substantial burden as the host country for over 2 million Syrian refugees, spending approximately US$6 billion with limited support from the international community, which should step up its financial and other support to Turkey in order to improve access to education for Syrian children. But Turkey too should do more to ensure that its own policies are being enforced, and to address the remaining practical obstacles that prevent ensuring Syrian children’s access to education. This includes:

- Implementing accelerated Turkish language programs through the public school system to overcome the language barrier for Syrian students;

- Ensuring that all provinces and public schools comply with the national regulation guaranteeing Syrian children’s access to the public school system;

- Utilizing existing monitoring mechanisms to track school dropouts and encourage attendance;

- Investing in training for teachers and school personnel tailored to the unique challenges of educating a non-Turkish speaking refugee population;

- Working with implementing partners such as the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to disseminate accurate information to Syrian refugees, including those in harder-to-reach areas, regarding the procedures and requirements for school registration;

- Providing widespread access to work permits for Syrian refugees in order to offer disadvantaged families access to labor protections and the possibility of steady minimum-wage work, and in doing so to mitigate the high rate of child labor among Syrian refugee households.

Failing to act urgently to ensure Syrian children’s access to education in host countries like Turkey may have a ruinous effect on an entire generation of children like Mohammed. Securing their education now will reduce the risks of early marriage and military recruitment, stabilize economic futures by increasing earning potential, and ensure that today’s young Syrians will be better equipped to confront uncertain futures, whether it involves rebuilding their country and rehabilitating Syrian society, or contributing to their communities elsewhere in the world.

Methodology

This report is primarily based on research conducted in June 2015 in Istanbul, Izmir, Turgutlu, Gaziantep, Mersin, and Ankara. Human Rights Watch interviewed non-camp Syrian refugee families to assess their educational situations. We focused on non-camp refugees because of the low rate of enrollment among non-camp refugees in comparison to the high rate inside camps.

In total, Human Rights Watch interviewed 50 households in person and one household over the phone. Not all members of each household were present during each interview; of the 136 individuals present and directly interviewed, 71 were children between 5 and 17 years old. Those present included 18 adult men, 42 adult women, 35 boys, and 36 girls. Including members who were not present, Human Rights Watch obtained information on the conditions of 233 individuals, of whom 113 were school-aged children. Of the 48 households, 19 identified themselves as Arab, 15 as Kurdish, 2 as Turkmen, 1 as Circassian, and the rest did not disclose their ethnicity. They originated from Aleppo, the Aleppo countryside, Damascus, Idlib, Afrin, Qamishli, Amuda, Ras al Ayn, Hasaka, and Homs. The interviewed families were identified through through local and international NGO referrals and contacts within the Syrian refugee community of each city.

The majority of interviews took place in private homes, while six took place in public parks and a refugee service center waiting room. Human Rights Watch was careful to conduct all interviews in safe and private places. Interviews were conducted in Arabic and Kurdish, with the assistance of an interpreter. All interviewees received an explanation of the nature of the research and our intentions concerning the information gathered, and we obtained oral consent from each interviewee. All were told that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. Participants did not receive any material compensation. Human Rights Watch has withheld identification of individuals and agencies that requested anonymity.

We did not undertake surveys or a statistical study, but instead base our findings on extensive interviews, supplemented by our analysis of a wide range of published materials. Human Rights Watch also met with representatives of the Turkish Ministry of National Education (MONE), the Directorate General of Migration (DGMM), the municipality of Gaziantep, and the Syrian Interim Government’s Ministry of Education. In addition, we met with representatives from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), international and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Syrian school directors, informal education providers, and teachers. We also consulted with experts in education in emergencies and Turkish education policy.

Note on currency conversion: this report uses an exchange rate of 2.78 TL per US Dollar.

I. Background

Syrian Displacement to Turkey and Turkey’s Response

Since Syria’s armed conflict began in 2011, over 2 million refugees have fled across its border into Turkey,[2] which has maintained a largely “open-door” policy towards the incoming asylum seekers.[3] UNHCR and other observers have lauded the “consistently high standard”[4] of its response to this influx of newcomers, which has turned Turkey into the largest refugee-hosting country in the world.[5] Turkey’s policies have evolved over the last four years, shifting from an emergency response to one that takes into consideration more long-term concerns of protracted displacement.

According to the Turkish government, as of February 2015 it had spent $6 billion overall on the Syrian refugee crisis, while the total contributions it received from international donors stood at $300 million.[6] Turkey’s investment represents the largest contribution “made to date towards addressing the Syrian [refugee] crisis.”[7]

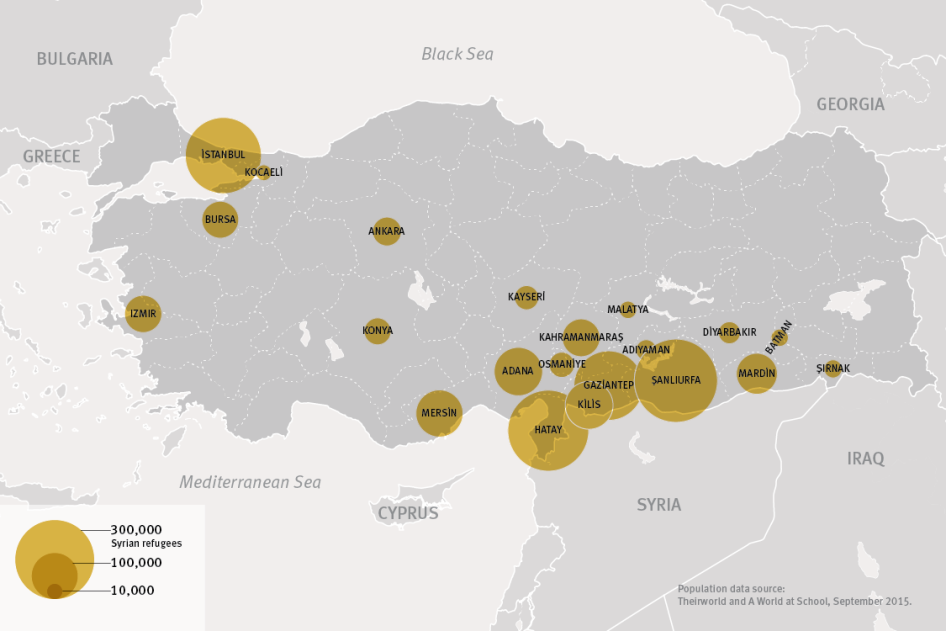

The Turkish government has built 25 camps near the Turkish-Syrian border, where, as of August 13, 2015, it sheltered 262,134 Syrian refugees with the camps at their full capacity.[8] The other 85 percent of the refugee population are “urban refugees,” scattered in towns and cities throughout the country. The largest concentration lives in the southeastern provinces on Syria’s border, where some municipal populations have increased by 10 percent or more due to the refugee influx.[9] However, settlements of refugees from Syria can also be found in major urban centers such as Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir. As of January 2015, Istanbul’s population of refugees from Syria had reportedly reached 330,000.[10]

While Turkey is a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, it is the only country that maintains the convention’s original geographical limitation to refugees from Europe.[11] Turkish law, therefore, does not recognize individuals fleeing violence or persecution in Syria as refugees or grant them asylum. Thus in the early days of the crisis, the Turkish government referred to the Syrian arrivals as “guests.”[12] In October 2011[13] Turkey established a “temporary protection” regime under which Syrians and Palestinian residents in Syria were granted entry into Turkey without visas, protection from forcible return, and access to humanitarian assistance.[14]

Change in Legal Status for Refugees from Syria

In April 2014, a comprehensive migration law, the Law on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP),[15] came into force, which strengthened the temporary protection scheme for Syrians and Palestinians from Syria by granting them formal legal status in the country and officially allowing them to live outside camps. It also created a new Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) under the Ministry of Interior with responsibility for asylum matters, including the registration of Syrian refugees.[16] Prior to this, registering refugees, building camps, and coordinating service delivery to refugees both inside and outside the camps had been the responsibility of Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) under the Turkish Prime Ministry.

A subsequent regulation issued in October 2014[17] clarified the rules and procedures for registering temporarily protected persons, as well as their rights and entitlements.[18] It states that beneficiaries can receive free access to emergency healthcare; identity cards indicating their lawful residence in the country; access to “accommodation sites” that provide shelter, food, and other services; the right not to be detained for their irregular entry; access to family reunification; access to legal consultation and free translation services; and protection from forcible return to their countries of origin, also known as refoulement.[19] While the regulation did not introduce an explicit right to work or social assistance, it did indicate that such resources could be made available to beneficiaries.[20]

Educational Services for Syrian Refugees

In September 2014, Turkey’s Ministry of National Education (MONE) issued Circular 2014/21, which laid out new regulations for the education of temporary protection beneficiaries in line with the April migration law. Among other provisions, the circular established provincial commissions tasked with carrying out the education-related measures outlined in the law and regulation, created an accreditation system for Syrian “temporary education centers,” and decreed that a “foreigner identification document”—not a residency permit—was sufficient for registration in the Turkish public school system.[21]

The Turkish government has clearly expressed its commitment to educating Syrian refugee children. On October 2, 2015, deputy undersecretary for education Yusuf Buyuk stated, “If we cannot educate these students, they will fall into the wrong hands, they are going to be exploited by gangs, criminals….We are trying to improve the standards in our country which means also improving standards for Syrians.”[22] The issuance of Circular 2014/21 arose out of the Ministry’s recognition that it needed to work toward the “elimination of barriers … such as language barriers, legislative barriers, and technical infrastructure gaps” that prevented Syrian refugee students from attending school.[23]

There are two parallel systems of formal education for Syrian primary and secondary school-age children in Turkey, as well as several available routes for non-formal education.[24] The provision of educational services in Turkish public schools and temporary education centers is the result of a partnership between MONE, UNICEF, UNHCR, and other donors. While MONE is primarily responsible for the coordination and supervision of these services, UNICEF and UNHCR provide technical and financial support. For example, MONE consulted with the agencies on the development of Circular 2014/21.[25] UNICEF has also provided technical assistance for the registration and monitoring of Syrian students in the MONE database (known as YOBIS),[26] contributed resources for the construction of temporary education centers,[27] and provided Syrian volunteer teachers in temporary education centers with financial incentives and training.[28] UNHCR has also provided teaching materials for temporary education centers in urban areas.[29]

While the Ministry of National Education estimates that the additional cost of educating Syrian students in 2014-2015 was 700 million TL (approximately $252 million), it does not allocate specific funds for the education of Syrian refugees. Rather, it meets relevant expenses within its general budget; therefore, more specific data on its overall spending on the education of Syrian refugees is not available.[30]

Turkish Public Schools

Turkish public schools are officially available to all Syrian primary and secondary school-aged students as long as they are registered as temporary protection beneficiarieswith the government.[31] If they are able to present a government-issued ID card (also known as a “Foreigner ID”), they may register at any Turkish school under Circular 2014/21.[32] Enrollment is free, although parents may be charged additional “activity fees” throughout the school year.[33] In urban centers, schools are generally available within walking distance of residential neighborhoods, and in rural areas of the country the government provides buses for free.[34]

As of 2012, the Turkish school system operates on what is called the “4+4+4” system: 12 years of free compulsory education, comprising 4 years of primary school, 4 years of lower secondary school, and 4 years of upper secondary school. Students may also enroll in vocational training—including religious vocational training—starting from the fifth grade.[35]

In 2014-2015, there were 36,655 Syrian students enrolled in primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary school in the Turkish public school system. [36] They represented .22 percent of the total in-school population in Turkey.[37] The enrollment figure reflects the impact of Circular 2014/21 on enrollment in public schools, which jumped from 7,875 in the prior school year.[38] However, the number still represents merely 6 percent of the school-aged population among Syrian refugees, which means the vast majority of Syrian children who can theoretically access Turkish public schools are not doing so in practice.

The education system in Turkey is highly centralized, and individual schools are not allocated direct funds over which they have discretion. [39] This has led one Turkish think tank to conclude that “schools do not have enough room to come up [with] and fund effective solutions that would cater to the needs of Syrian children.”[40] In the southeastern provinces of Turkey, which host the highest percentages of Syrian refugees,[41] schools “were already in a disadvantaged position [prior to the arrival of the Syrian population] in terms of basic education indicators such as enrollment rates, student per teacher, or student per classroom ratios.”[42] Public educational services in these areas are “extremely strained” now that they are faced with an influx of Syrian students.[43]

Temporary Education Centers

Temporary education centers are primary and secondary schools that offer a modified Syrian curriculum in Arabic.[44] They operate both within and outside refugee camps. The curriculum they use is largely the same as the official curriculum used inside Syria, with partisan references to the Syrian government, including Bashar al-Assad and his family and Ba’athism, removed.[45] The Syrian Interim Government’s Ministry of Education, which is headquartered in Turkey, manages and distributes the curriculum in cooperation with the Turkish Ministry of National Education (MONE).[46] In the fall of 2014, MONE began registering non-camp temporary education centers so that they could be incorporated into the national education framework. In June 2015, MONE also supervised, for the first time, the administration of a Syrian baccalaureate exam (issued upon completion of high school) that will be recognized by Turkish universities. Approximately 8,000 students registered for the exam.[47]

Temporary education centers are not widely distributed throughout the country, but rather are located in 19 of Turkey’s 81 provinces, particularly in cities that host large Syrian populations.[48] During the 2014-2015 school year, there were 34 temporary education centers in camps and 232 outside of camps. In 2014-2015, total primary and secondary enrollment in temporary education centers was 74,097 in camps and 101,257 outside camps.[49]

While some temporary education centers are operated by local authorities, others have been established by charitable associations and individual donors.[50] Many charge tuition ranging from 440 TL ($158 USD) to 650 TL ($234) per year, and also require additional bus fees for transportation (ranging from 60 TL ($22) per month to 120 TL ($43) per month), which is unaffordable for many families[51]; other schools face overcrowding that limits the number of students that can access them or reduces their quality of the education.[52]

Non-Formal Educational Services

Some out of school children receive non-formal education from mosques, unregistered temporary education centers, or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). There is no comprehensive data available on how many children are accessing these services in Turkey. According to parents whose children are attending mosque lessons, such programs are entirely devoted to Quranic study and are often free.[53] Temporary education centers that remain unregistered or that have not met MONE’s regulatory standards do not receive accreditation of any kind, and students do not receive recognized certificates upon the completion of their studies.[54] NGO service centers offer classes in English, Arabic, Turkish, computers, music, and other subjects once or twice a week.[55]

Three families interviewed for this report were sending their children to Quranic lessons at local mosques in lieu of formal education. These programs are unregulated by the Turkish government and are not an adequate substitute for a regulated, accredited school. Alaa, 11, had been attending such a program for several months at the time of her interview, and she told Human Rights Watch:

I don’t enjoy learning there very much. They only teach us to memorize hadith [the sayings and deeds of the Prophet Mohammed], that’s it. I’m good at it, but it’s really boring. I like learning Arabic, but we are only learning the alphabet and how to read and write. I miss the other subjects.[56]

II. Barriers to Education

As of October 2015, there were approximately 708,000 Syrian refugee children aged 5 to 17 in Turkey.[57] While around 90 percent of school-aged children living in the 25 Turkish government-run camps were enrolled in school in 2014-2015,[58] children in camps represent only 13 percent of the Syrian refugee school-aged population.[59] Outside the camps, the educational situation for Syrian refugee children is bleak: enrollment in both temporary education centers and public schools in 2014-2015 was an estimated 25 percent.[60]

In making Turkish public schools legally accessible to Syrian refugees and accrediting Syrian temporary education centers, the government of Turkey has taken important steps toward realizing Syrian refugee children’s right to education.

However, removing legal obstacles is only a first step. In practice, there are many more obstacles that prevent Syrian children from attending school. Many children and parents told Human Rights Watch that they had not been able to enjoy Turkey’s guarantees of free education because of economic hardship that has driven children into the workforce, the Turkish language barrier, and difficulties with social integration. The Ministry of National Education has stated that it aims to have 270,000 Syrian children in school by January 2016 and 370,000 in school by the end of the 2015-2016 school year.[61] Addressing the barriers outlined below will be crucial to meeting those goals.

Fatima, a mother of four living in the coastal town of Mersin, told Human Rights Watch that her two school-aged sons, 9 and 11, were not in school because “we don’t know anything about how to register or if they are allowed to go, and they are working now.” She explained that her husband does not have a work permit, so he works illegally for wages far below his work-authorized coworkers. Her sons work, she said, because her husband’s income barely covers living expenses and, since he is uninsured, their healthcare costs. [62]

Ali, 13, told Human Rights Watch that he stopped going to school in the Aleppo countryside when his school was shelled. He arrived in Turkey in May 2014 and was not enrolled in school. “We weren’t allowed to go in the beginning because we didn’t have a residency permit. We have the Foreigner IDs now and I want to go to school, but I wouldn’t understand anything. I don’t know much Turkish and it would be too hard.”[63] His father added, “There is also tension and discrimination in this area against Syrians, and we don’t want them to fight with our kids.”[64]

The majority of families whose children were not in school said that they would prefer sending their children to temporary education centers, but would also be willing to send them to Turkish public schools if their first choice was not available. Even the parents who said that a Turkish education was “useless,” because they planned to return to Syria someday, said they would still enroll their children in a Turkish school if they could, but that they had not done so because they believed residency permits were required for registration or they were apprehensive about language issues.[65] Similarly, a 2014 educational needs assessment for Syrian refugees conducted in southeastern Turkey found that 80 percent of adult respondents said they would send their children to Turkish schools if possible.[66]

Of the 50 households interviewed for this report, 32 families cited economic circumstances as a major barrier or influential hardship on their access to both Turkish schools and temporary education centers; 20 families identified language as a barrier or hardship with regard to accessing Turkish schools; 17 families identified social integration with Turkish children as an issue; 11 had no information on registration procedures or mistaken information on requirements; 4 reported being denied access at least once prior to the issuance of Circular 2014/21 and subsequently had not tried again; 2 reported being wrongfully denied access by school administrators; and 5 said the lack of nearby temporary education centers had prevented them from enrolling in a Syrian school.

Language

With the exception of Syrian Turkmen, most Syrian refugee families come to Turkey with no knowledge of the Turkish language. Parents, children, NGO representatives, and other stakeholders interviewed for this report frequently cited language as a significant barrier to Turkish schools. Of the 50 households interviewed for this report, 8 specifically cited language as the primary reason why their children were not attending Turkish schools, and an additional 12 cited language as a hardship that significantly influenced their children’s access to or experience in school.

The impact of this barrier appears to be closely correlated to age.[67] A Turkish primary school teacher told Human Rights Watch that he had observed this dynamic in his own school:

The little children have the easiest time adapting to the Turkish school because they can learn Turkish quickly. Once you get to fourth or fifth graders, though, it is much harder. That’s why we have only a few older Syrian kids in the school.[68]

Families also indicated that younger children learn Turkish faster while simultaneously facing less severe academic consequences when they struggle with schoolwork during the adjustment period.[69]

The Association for Solidarity with Asylum-Seekers and Migrants (ASAM), a Turkish NGO, operates a Multi-Service Center for local refugees in Istanbul. An ASAM representative told Human Rights Watch that the center closely monitors the educational status of families who benefit from the center’s services and had also observed the significance of the language barrier on enrollment:

We strongly encourage families to keep their children in schools. When they do pull them out, it tends to be because they are not learning anything due to the language barrier, or financial reasons.[70]

Lack of Language Support or Accelerated Learning Programs

The impact of the language barrier on Syrian students’ ability to access Turkish schools is considerable. One report concluded that “special literacy programmes and remedial classes are of extreme urgency” so that refugee youth and children can attend Turkish government schools where Turkish is the language of instruction.[71]

Currently, there is no formalized or systematic support for non-native speakers in the Turkish public school system, although a Ministry of National Education official told Human Rights Watch in June 2015 that the ministry was in the early stages of developing an accelerated language learning program for temporary protection beneficiaries.[72] In September 2015, the Ministry confirmed that “language cards and activity sets for the first graders” had been developed, and the development of more advanced training materials would “begin in the next two months.”[73] Similarly, the United Nations Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan in Turkey—a partnership between UNHCR, UNICEF, and national institutions—stated in its education sector updates for April, May, and June 2015 that

[e]xisting efforts to accommodate refugee children in the national system will be scaled up through the provision of teaching materials and capacity to teach Turkish as a foreign language to refugees.[74]

Such programs are urgently needed. A Turkish primary school teacher told Human Rights Watch that schools were unlikely to develop similar initiatives on their own, as the Ministry would need to pay teachers for the extra hours of work if they were responsible for the instruction.[75] Limited Turkish language classes for children do exist in NGO-run refugee service centers, but those services are limited to families who live in cities where such centers operate, such as Istanbul and Gaziantep.[76] In addition, many families interviewed for this report told Human Rights Watch that they had no knowledge of such programs.

The Ministry of National Education offers Turkish “literacy and language classes” for Turkish nationals through the Directorate of Lifelong Learning,[77] but temporary protection beneficiaries do not have explicit access to them via the relevant regulation and MONE circular and only one family interviewed by Human Rights Watch had ever heard of these classes.

Aisha, 40, said she had sent her 11-year-old son Mohammed and 13-year-old daughter Barfeen to a Turkish literacy class at their local primary school in Izmir for a few months; the class ran for three hours a week. “The other students were illiterate older Turkish women, and our kids were the only children. Our neighbors were the ones who told us about it.”[78]

Omar, a 42-year-old is a father of six from Aleppo, told Human Rights Watch that his children were not enrolled in school in Izmir, where the family lives, because although he cared about their education, he felt it would be “no use to send them to Turkish school unless they could start with Turkish classes.”[79]

Jabber, 20, said that he fled Qamishli with his widowed mother and younger siblings to avoid being conscripted into military service in Syria. Human Rights Watch interviewed him in Turgutlu; he said that his 14-year-old and 13-year-old brothers were not present because they were working. “The Turkish language barrier is a big reason the boys are not in school. We plan to return to Syria soon because life is very difficult here.”[80]

Even for Syrian students who managed to enroll in Turkish schools, the language barrier was a significant obstacle. Omar, 13, arrived from Damascus with his family in Istanbul at the end of 2012 when he was in the middle of fifth grade. Unlike most Syrian refugee households, his family had a residency permit, and he was able to enroll in a Turkish school immediately at his grade level. However, he struggled to learn a new language while adapting to a new environment, and his classmates often mocked him for his difficulty speaking Turkish, he said. His mother Rana told Human Rights Watch,

He cried every morning and said he didn’t want to go to school. One of Omar’s teachers at the Turkish school told me there was no use sending him to the school when he didn’t know any Turkish. The teacher told me about a language institute that might help, but the institute informed us that it only accepted university students. We looked around and couldn’t find anything that helped teach Turkish to children.[81]

Omar was able to enroll in a Syrian temporary education center the following year, but many of his peers are not so fortunate. Rasha, 16, told Human Rights Watch that when she first arrived in Izmir from Qamishli, Syria in August 2013, the local Turkish school would not allow her to enroll. One year later, after MONE had issued Circular 2014/21, she again attempted to enroll in school. The administration told her she was allowed to do so, but she would need to enroll in tenth grade with her peers.

That condition was too hard for me because of the Turkish language barrier. We asked if I could enroll in eight grade instead, but the school director said no. The language barrier made it impossible for me to attend.

Rasha enjoyed going to school in Syria. “Now that I can’t go to school, it’s a tough situation. It’s hard to get used to it. I work occasionally, filling in for my sisters at the factory. When I picture my future, I see nothing.”[82]

Lack of Flexibility with Grade Placement

The language barrier is often compounded by the lack of overarching guidelines for registering Syrian students in the Turkish system when they have limited language ability and, often, several years of missed education. The 113 school-aged children present in the households interviewed had lost an average of two years of school since the war began. While Human Rights Watch interviewed 11 children who had been placed several grades below their age level in Turkish government schools to accommodate for their limited Turkish proficiency or years of missed education, 8 reported that their local public school required them to register according to their age. Interviews with children showed that this practice can doom older children, in particular, to failure, and serve as a powerful deterrent for some who would otherwise like to continue their education.

Samir and MohammedSamir, 11, and Mohammed, 7, are brothers who live in the coastal city of Izmir. Samir does not attend school; instead, he spends his days in a shoemaking workshop with his father, where he works full-time for less than minimum wage.[83] Mohammed has completed the first grade at his local public school, where he thrived both academically and socially. Their story illustrates the factors that affect Syrian enrollment in formal education, and what a crucial difference effective implementation measures can make for an out-of-school Syrian child. Samir and Mohammed fled Aleppo with their parents when the war made their lives untenable in early 2013, the family said. They first moved to Beirut, Lebanon, where the children were unable to attend school due to overcrowding. In 2014, the family moved to Izmir, Turkey, where they had some relatives. After they received their Foreigner ID cards, their parents dutifully went to register them for school that September. The school was within walking distance, free, and agreed to admit the two boys—but school officials placed Samir in fifth grade and Mohammed in first. Mohammed was young enough that he was able to adjust quickly to the new environment and language. His family showed a Human Rights Watch researcher Mohammed’s end-of-year certificate for 2014-2015, which bore excellent marks across all subjects. He is the only Syrian student in his class, but he said: I like school—I have a good teacher and good friends who are very polite and respectful. I speak Turkish, not 100 percent yet, but I am learning. I want to finish school and become a teacher someday. My Dad says I’m doing so well and once I’m fluent in Turkish I’ll do great.[84] In contrast, Samir had minimal proficiency in Turkish at the time, and said he found it impossible to follow his lessons. I only finished second grade in Syria. My school in Aleppo was shelled, so I missed third grade. I didn’t go to school in Lebanon…When I enrolled in school here, because of language issues I just didn’t benefit at all. I felt very isolated. The other kids would mock me, but I didn’t understand what they were saying. My teacher was nice to me but got frustrated because we couldn’t communicate with each other.[85] According to Samir’s father, “We requested that the school place him in a lower level. They said according to his size and age, it would be impossible to let him join a younger class. We tried to explain how hard the language is for Arabs, but they said no. They weren’t interested in [finding a solution].”[86] After one week, Samir refused to attend school anymore. Samir and Mohammed’s father concluded that “the Turkish schools don’t care if we send our kids or not. After Samir dropped out, they didn’t bother to check up on him.” Due to research constraints, Human Rights Watch did not contact Samir’s school to obtain its perspective on these events. However, if his father’s account is accurate, the school did not take reasonable steps to accommodate Samir’s circumstances and may have failed to comply with the Turkish education ministry’s own provision that “school administrations … provide support and assistance to those who have adaptation difficulties.”[87] |

A Syrian family living in Turgutlu, a large town in the Aegean region of Turkey, described strikingly similar experiences to Samir and Mohammed’s. Fatima, a mother of three from Homs, told Human Rights Watch that her 8-year-old daughter, Abeer, had finished first grade in the local public primary school in June 2015:

Abeer was one of the best in her class this year. She’s one year behind her classmates but the primary school allowed her to enroll in a grade below her age group [when we enrolled in September 2014].[88]

However, the local secondary school had a different policy. Fatima says that when she went to enroll her 16-year-old daughter, Loreen, at the same time, the director informed her that she would “have to join her age group, no exceptions; she cannot start at a lower grade.” Loreen had been cut off from her school in Homs in the seventh grade due to heavy shelling in the area, and she spoke no Turkish.

Her mother explained, “The language makes it impossible to learn. I asked the school about language help and they said there wasn’t any.” Attending school at her regular grade level seemed an insurmountable hurdle, and Loreen did not enroll. Loreen’s mother was devastated:

In Syria she was really good in school, and I feel very bad as a mother about this. Their whole generation has been cut off. [She] felt blocked…Loreen felt the worst about losing her education.

Loreen was not present for the interview, because she was working in a dried-fruit factory, where she is now employed full time, according to her mother.[89]

A more nuanced approach to grade placement, along with other forms of support, might increase the numbers of Syrian children who attend Turkish public schools and the quality of their learning experiences.

UNHCR in Central Europe has recommended that Ministries of Education establish guidelines for refugee student grade placement that take into consideration “language skills, academic competency and past academic studies [and] the age of the student.”[90] While a student’s ability to speak the national language should be a factor, it should not be the only factor, and Samir and Loreen’s experiences do not signal that Turkish schools should universally place Syrian students with younger classmates in order to accommodate their language level. As one NGO in Istanbul pointed out, “[Being] placed in a lower grade…can be hard psychologically and socially and become an incentive not to attend” as well.[91] Rather, grade placement decisions should take place within nuanced consideration of relevant factors for each individual student. For some students, dropping back several grades may, on balance, be beneficial.

Rawan, 14, fled with her family from Aleppo in October 2013, and she had just finished the fourth grade at a Syrian temporary education center in Istanbul when Human Rights Watch interviewed her in June 2015. The temporary education center had allowed her to drop back four grades because she had missed four years of school—two in Syria because of shelling in the neighborhood, and two in Turkey because of financial constraints. Financial aid from a private donor finally allowed her to attend school starting in January 2015. While being older than her classmates was difficult at first, she was able to adjust:

The other kids laughed at me because I’m so much bigger than them. I would come home and cry every day. But then I started to get good grades, and I’m glad to be in school.[92]

Sara, 10, was placed in the second grade at her local public school in Turgutlu to account for the education she missed while in Syria and during her first year in Turkey, as well as her limited facility in the Turkish language. Although she was two years older than her classmates and the only Syrian in her class, she told Human Rights Watch that she had a “good experience” overall.

I finished the year ranked third in my class and fifth in my grade overall. My teacher was very good and we liked each other very much. All my classmates were my friends. I learned Turkish quickly, and now I think I speak better than the Turks! I can’t wait for to start school again. I’ve already packed my school bags for next year even though my summer vacation just started this month.[93]

Economic Hardship

For many families interviewed by Human Rights Watch, financial hardship is a crucial factor that determines whether or not their children can go to school. While Turkish schools do not charge tuition, there are associated costs—school supplies, activity fees, and parent-teacher association fees—that can tip the scales for economically disadvantaged Syrian families.[94]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has expressed concern about such hidden costs in education.[95] And for families that cannot access Turkish schools because of language, social integration difficulties, or other issues, the alternative temporary education centers are often out of reach because of tuition costs and transportation fees.

Nisreen, 28, is a widowed mother of four from Aleppo who lives in Gaziantep. She told Human Rights Watch, “We don’t have money, so my three younger kids are not in school. The [temporary education center] closest to here is too expensive: each child has to pay 60 TL ($22) per month for the bus. We can’t afford that. My older son works as a car mechanic, but our rent is 225 TL ($81) a week.”[96]

Um Mohammed lives in Gaziantep with her youngest son, Bara, who is 15 years old. In Syria he finished 7th grade, she told Human Rights Watch.

After the conflict began we didn’t feel safe continuing to send him [to school], so he lost two years while in Syria. Then a shelling killed my husband so on the first day of Ramadan in 2014, we walked here to Turkey. Bara works washing cars; when he first dropped out of school, he would cry because he missed being in school so much. Now whenever he sees [peers] that are in school, it upsets him because he envies them … it’s shameful—he should be studying too; instead, [he is] working and getting paid 60-100 TL (approximately $21 to 35) a week.[97]

Um Mohammed’s three grandchildren also live in Gaziantep and do not attend school. “They can’t afford it,” she said. “My grandson is 11 and should be in 5th grade, but instead he works at a garment factory. His sisters sit at home all day and don’t do anything. The nearest [temporary education center] is far away, and requires a bus we can’t afford.”[98]

Like Um Mohammed, the majority of interviewed families with out-of-school children told Human Rights Watch that they relied on those children, as young as eight, to be sources of income for the household. Recent reports indicate that the Syrian refugee influx has created a spike in child labor throughout Turkey.[99]

A 2014 UNICEF report on the impact of the Syrian conflict on children’s lives estimated that one in ten Syrian refugee children in Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, and Turkey works.[100] According to official statistics, almost 900,000 children—both Turkish and non-Turkish—are estimated to be working in Turkey, around 300,000 of whom are between ages 6 and 14.[101] However, these official figures likely underrepresent the reality, particularly since illegal child labor occurs outside normal monitoring mechanisms.[102]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has expressed concern about the lack of regular data covering child poverty and child labor in Turkey, and has recommended that Turkey begin collecting that data and disaggregating it by gender, geographic location, ethnicity and socioeconomic background to improve monitoring of child rights issues.[103]

Under Turkish law, the minimum age of work is 15,[104] and the minimum age for hazardous work is 18.[105] In 2013, the Turkish government extended the minimum wage to workers of all ages, including 15 year olds who were not previously included in minimum wage protections.[106]

While these labor protections do not explicitly extend to non-citizen children, Turkey has also ratified the international conventions that prohibit child labor, including the International Labour Organization Minimum Age Convention (ILO C.138),[107] the ILO Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention (ILO C. 182),[108] the Convention on the Rights of the Child,[109] the International Convention on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, [110] and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.[111]

Families interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that their children were working in garment factories, dried fruit factories, shoemaking workshops, and auto mechanic shops; some picked cherries or worked as agricultural laborers, while others sold tissues, water, or dates on the street. Studies, consistent with the findings of Human Rights Watch’s research, have found that refugee children are sometimes the family breadwinners. Refugee parents “are torn because they want their children to learn and secure a better future but adults tend to struggle to find work; it is easier for adolescents to find paid work in Turkey…. As a result, many young refugees work rather than study.”[112]

RadwanRadwan, 11, and his widowed mother told Human Rights Watch that they fled Damascus when the orphanage[113] where he lived with his three siblings there was shelled in March 2013. In Gaziantep, his mother explained, “None of my children are in school because we cannot afford it. We need them to work so we can eat.”[114] Radwan told a Human Rights Watch researcher that his 12-year-old twin brothers and 10-year-old sister were not present for the interview because they were working, but it was his day off. He explained, “I was in fourth grade in Syria when I stopped attending school. I loved school. I liked to study math, and I miss going to school very much.” He said he works more than 12 hours per day, seven days a week, and earns 40 TL, or $14 per week. “But the tailor I work for is nice and treats me well. I work from 7:30 a.m. to 8 p.m. every day. My brothers earn the same salary, but my younger sister earns 30 TL [$11] a week.” Radwan’s family lives in an abandoned shop with no bathroom where they pay 250 TL ($90) a month for rent and utilities. |

Several NGOs emphasized to Human Rights Watch that the child labor crisis is closely related to the issue of work permits for Syrian refugees in Turkey. Aside from language, the lack of a legally protected right to work is what separates poor Syrian refugee families from poor Turkish families, who still largely manage to send their children to school.[115]

The Fair Labor Association has reported that employers in Turkey often take advantage of Syrian refugees by paying them below-minimum wage, forcing them to work long hours in unsafe settings, and subjecting them to unreasonable deductions from their pay.[116]

Families interviewed for this report confirmed these findings. Of the 50 households interviewed, 40 confirmed that at least one parent or adult member of the household regularly worked outside the home. However, of those 40 households, 3 had a child aged 15 who was working, and 8 had a child younger than 15 who was working. In addition, 4 female-headed households relied on their children as their primary source of income.

Families with both adults and children in the workforce reported that the lack of labor protections meant the adult workers were often exploited by employers—paid significantly less than their Turkish counterparts,[117] sometimes denied pay altogether,[118] and received no benefits.[119] As a result, they felt they had no choice but to ask their children to work as well in order to cover basic costs of living.

Of the Syrian households interviewed for this report, no one working full-time without a permit was earning minimum wage, which at the time of interviews was 949 TL per month, or approximately $341.[120] On average, those who disclosed their income were earning 479 TL ($172).

The October 2014 temporary protection regulation states that “procedures regarding the employment of persons benefiting from temporary protection shall be determined by the Council of Ministers” and that beneficiaries “may apply to the Ministry of Labour and Social Security for receiving work permits to work in the sectors, professions and geographical areas … to be determined by the Council of Ministers.”[121] Thus, in principle, the regulation acknowledges the possibility of lawful access to the labor market, but any such access would need to come through subsequent regulations that have not yet been issued.

In the months following the publication of the Temporary Protection Regulation, some news media reported that the Ministry of Labor and the Interior Ministry were developing legislation intended to widen access to work permits for Syrian refugees.[122] However, on August 7, 2015, the Ministry of Labor and Social Security announced that no such plan existed, and Turkey would not be granting refugees work permits under any general program.[123] Unless Turkey issues regulations that allow Syrians to work legally and enjoy the protection of Turkish labor laws, refugee families will continue to struggle, and their children’s educations will be cut short.

One 38-year-old father of six living in Izmir told Human Rights Watch that his 12-year-old oldest son Ahmed was not in school because he was working:

He makes bags in a workshop. He works five-and-half days a week and earns 500 TL ($179) per month…. I want to enroll my younger children in school next year, but Ahmed, we need him to help with income. If he doesn’t work, we can’t eat. Rent and utilities are barely paid month to month as it is.[124]

Ibrahim, 15, lives with his widowed mother and two brothers in Mersin, where he works painting cars from 8 AM to 6:30 p.m., six days a week, for about 300 TL ($108) per month. He has not attended school since the seventh grade, in 2013, when barrel bombs destroyed his Aleppo neighborhood and his family relocated to the countryside, he said.[125] Later, when Islamic State (also known as ISIS) militants began to encroach on the vicinity, they fled to Turkey. His brothers proudly told a Human Rights Watch researcher that Ibrahim was a star student who excelled in all subjects. When asked whether he missed being in school, Ibrahim responded:

I loved studying math. I do really miss school, and I wish I could go back. It’s really hard to be working compared to a student’s life—it’s very different circumstances from what we used to have. Our lives have totally changed. I have no friends, Turkish or Syrian. It’s very lonely. We don’t really have time for friends, working ten-and-a-half hours every day. It is not the safest workplace—I have back and leg pain from being on my feet all the time, and lung issues because of all the chemicals.[126]

Ibrahim’s 27-year-old brother Omar described the Turks in his neighborhood as “also poor,” but believed most of them were able to send their children to school.[127] In fact, while poverty does affect the out of school population of Turkish nationals,[128] overall Turkish enrollment levels in 2014-2015 remained relatively high, reaching 96.3 percent for primary school and 94.35 percent junior high school.[129]

The Association for Solidarity with Asylum-Seekers and Migrants (ASAM), a Turkish NGO that operates a refugee service center in Gaziantep, told Human Rights Watch that the provincial directorate of the Ministry of Family and Social Policies (MFSP) had consulted them regarding the alleviation of child labor among Syrian refugees in the area.[130] On June 12, 2015, World Day against Child Labor, the MFSP erected posters in refugee service centers aiming to raise awareness about the detrimental aspects of child labor.[131] Public information campaigns can be beneficial, but are unlikely to change patterns of behavior dictated by economic circumstances if no alternatives are available.[132]

As UNICEF has noted:

[T]he number of children begging or living on the streets cannot be addressed without also focusing on problems in the home or in schools that often force children onto the street…Child labour is largely driven by vulnerabilities caused by poverty and deprivation. Progress to eliminate child labour is therefore closely linked to reducing these vulnerabilities, mitigating economic shocks, and providing families with social protection and an adequate level of regular income.[133]

Syrian child labor in Turkey will almost certainly continue to persist until refugee families are offered a meaningful opportunity to make a living wage. As one Mercy Corps program coordinator told Human Rights Watch, “If adults could work legally, we expect that fewer children would work. They don’t need to make a lot of money, just come to an equal position with Turkish workers. As it is, there’s a shadow economy [of vulnerable Syrian refugee workers].”[134]

Social Integration

Interviewed families reported mixed experiences integrating with their host communities. Children attending Turkish public schools often described social tensions with their Turkish classmates, some of whom would mock them for their language errors or simply for being Syrian: “When I first arrived, the Turkish kids in the neighborhood made fun of me a lot because I couldn’t speak Turkish, and my father encouraged me to learn it as fast as possible,” explained Khamleen, 14, who arrived in Izmir from Damascus in March 2013.[135]

A Syrian Turkmen mother whose daughter will transfer from a Syrian temporary education center to her local Turkish school because they can no longer afford to pay tuition said her most pressing concern was her daughter’s social integration at the new school:

Switching will be hard in some ways because Turkish kids have issues with Syrian kids—they make fun of them even on the streets, yelling ‘Syrian, Syrian.’ Even though she speaks Turkish [because we are Turkmen], I worry.[136]

Seventeen of the 50 families interviewed for this report cited fears that their children would not integrate with or even be bullied by peers as an additional concern for why they did not want to send their kids to Turkish schools or why they were having difficulties succeeding there.

“I prefer for my children to study in a Syrian school because there are always problems for Syrian kids trying to assimilate in Turkish schools—they have issues with the Turkish kids,” said Khulood, a mother of three in Istanbul.[137]

Nabil, a father of five from the Aleppo countryside, also told Human Rights Watch he was unlikely to enroll his children in a Turkish school in Turgutlu: “There is discrimination against Syrians in the area and we don’t want our kids getting into trouble,” he said.[138]

Fatima, 12, originally from the town of Amouda in Syria, reported that bullying by other students was the primary factor behind her desire to drop out. She told Human Rights Watch that her Turkish classmates at a government school in Turgutlu had bullied her.[139] School administrators had placed her three grades below her age level when she enrolled in September 2014, because she had missed one year of school and was not fluent in Turkish. While she and her father reported that her Turkish vastly improved over the 2014-2015 school year and she was able to keep up academically, she was bullied by her classmates:

They would beat me when the teacher couldn’t see them, and my teacher didn’t know so wasn’t stopping it. My father visited the school director to complain, and the director said, ‘You should stop sending her to school if you’re worried about it.’ But my dad said I needed to study, so the director then told me not to interact with the other kids. I have no friends. It was difficult.… I didn’t enjoy anything about school this year. My teacher tried to scold the other kids, but they never stopped. They’d chant at me, ‘Syrian, Syrian,’ curse at me, and make fun of me for being older than them. In Syria, I loved school. I had friends; I loved learning. I miss my school in Syria very much.

Fatima said that she had decided not to return to school the next year. Her father, Hassan, had resigned himself to the notion that Fatima might drop out of school at a young age.

I will try my best to convince her, but if she really can’t go, what can I do? There are no Syrian schools around here. I will maybe put her in a Quranic program.[140]

A fundamental component to addressing social integration issues is the response of the school administrator and teachers toward Syrian students. One Syrian mother remarked:

Even my friends’ kids who are thriving in Turkish schools complain about being bullied or mocked by their classmates. I think the teachers probably don’t know how to help or intervene with this.[141]

But studies have found that equipping teachers of refugee children with the training to address social inclusion within their classrooms can help to mitigate this particular barrier.[142] UNICEF has observed that Turkish teachers “need professional development and support to work with Syrian refugee children,” including specialized training in dealing with children who have experienced trauma and violence.[143]

According to UNHCR, the “inherently political nature of the content and structures of refugee education can exacerbate societal conflict, alienate individual children, and lead to education that is neither of high quality nor protective.”[144]

The agency has noted that content of education should explicitly address “issues related to causes of conflict, good citizenship, [and] social cohesion” to combat the potential hazards of educating refugees and nationals together and harness its “important possibilities for social integration.”[145] It also said that studies have demonstrated the positive outcomes of teacher training on quality of teaching and relationships with learners.[146]

Like Fatima in the previous case study, Abir, 13, was also placed three grades below her age group and taunted by her classmates at a Turkish school in Turgutlu. But she described interventions by her teacher that sharply distinguish her experience from Fatima’s.

My teacher is very nice and treats me fairly.… Other school kids taunt me with ‘Syrian, Syrian’ and laugh at me sometimes, but inside the classroom the teacher will not allow this kind of behavior.… I’m older than all the other kids in my class by three years but no one gives me a hard time because the teacher won’t allow kids to make fun of me.

Abir explained that she is now one of the best students in her class and has a few close friends. She wants to be a surgeon when she grows up.[147]

III. Systemic Gaps

Provincial and Local Noncompliance

A crucial dimension to Syrian refugees’ access to education is provincial and local compliance with the relevant national directives.

Two families told Human Rights Watch that Turkish schools denied their attempts to enroll their children, despite their having presented the necessary documentation—a Foreigner ID card, as issued to temporary protection beneficiaries—under MONE Circular 2014/21.[148]

These cases represent a provincial and local failure to comply with national regulations and international principles, and while the problem was not widespread among families whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, it had ripple effects: an additional six families said they had not tried to register their children at Turkish schools because they had heard of similar incidents and assumed they would be denied.

All but three families interviewed for this report were in possession of the identification documents required to register in Turkish public schools. The exceptions were very recent arrivals who had not yet gone to the appropriate office, and refugees in Gaziantep who said the local office stopped issuing them in February 2015 due to a technical glitch.[149] However, two families reported that Foreigner IDs were not being accepted for school registration.

Rola, a mother of three and a former primary school teacher from Afrin who now lives with her family in Iskanderun, in Hatay Province, told Human Rights Watch that educating her children is a high priority, but that she was not able to enroll her children in school for lack of a residency permit despite attempting to do so after the issuance of Circular 2014/21:

We have the [Foreigner] ID cards but not a residency permit. I went to register my children in [a Turkish] school and the director said no, I couldn’t do it. I went to the police and they also told me I couldn’t do it. So I finally put my kids in a Syrian school which costs 500 TL (approximately US$180) a year per child. The school itself is very bad; the director doesn’t care about the children, and there’s no salary for teachers. There’s no [school] bus so I take a public bus to bring my kids to school each day, at 11 TL (approximately US$4) a day per child.[150]

Furthermore, the Syrian Interim Government’s Ministry of Education told Human Rights Watch that Gaziantep province schools have still been requiring residency permits to enroll in school, despite the directive from MONE to the contrary, possibly because of the high concentration of Syrian refugees there.[151]

All of the 14 families whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in Gaziantep said that their school-aged children—numbering 30 total—were either out of school or attending Syrian temporary education centers. Only one family had attempted to enroll their children in a Turkish school in September 2014; they said they had been denied access by school officials without explanation.[152]

The mother of that family, Aziza, described her efforts to register her 8-year-old daughter in a Gaziantep public school in September 2014:

We have the Foreigner ID cards. But when I went to the local Turkish school to register my daughter Bayan, they kept telling me to come back another time. I went five times. In the end, I just gave up.[153]

Bayan’s family cannot afford the bus fare or tuition for a temporary education center. Instead, her mother plans to register her for Quranic lessons at the local mosque. Ironically, if Bayan were allowed to register at the Turkish government school, she would face fewer integration obstacles than many of her Syrian peers, her mother explained: “Bayan speaks Turkish fluently because we are Turkmen; she would have a fine time at school [if they would let her attend].”[154]

Even if these noncompliant schools are outliers, interviews indicate that they can have a powerful deterrent effect when families hear from neighbors or relatives in tight-knit Syrian refugee communities that schools are rejecting Syrian students.

One mother in Mersin told Human Rights Watch that her 13-year-old daughter Amina had been out of school for three years, and her 9-year-old son Ali had never had an opportunity to attend school, and that an education was important for her children: “We don’t really care what language they’re learning as long as they’re studying. I want them to study even if we have a bad financial situation.” Yet when the family arrived in Turkey in July 2014, they did not attempt to register their children for school because they believed they would have been denied:

Our neighbors all told us there wasn’t a nearby Syrian school. To get to the closest one, we would have to pay 150 TL [roughly $54] per child per month for transportation. We can’t pay for that and also the rent and bills; my husband does not have steady work here. We don’t really know anything about Turkish schools, but we heard about families who tried to enroll their kids and were rejected.[155]

The Association for Solidarity with Asylum-Seekers and Migrants in Istanbul also told Human Rights Watch that some schools were resistant to complying with the MONE circular, whether because of a reluctance to teach Syrian children or for administrative reasons. It reported that most of its clients’ children were, in fact, enrolled in school. However, the NGO attributed this success in part to its own efforts to help parents overcome the barriers their children face. The NGO reaches out directly to resistant school administrators to advise them of the school’s obligations under the regulation.[156] For refugee families that live outside the range of NGO service providers or are unable to benefit from their advocacy for other reasons, a noncompliant school may present an obstacle that cannot be overcome.

MONE Circular 2014/21 includes a provision that provincial commissions be established in order to carry out actions and procedures concerning the education of Syrian refugees.[157] However, in an interview with Human Rights Watch, a MONE representative reported that provincial governments do not always comply with national directives due to political sensitivities regarding policies for Syrian refugees, and that the ministry does little monitoring of the commissions because of limited resources.[158]

One Syrian temporary education center director in Istanbul told Human Rights Watch, “The Turkish ministry of education helps us, but the extent depends on the provincial head.”[159]

Access to Information

Six of the 50 families interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they did not know whether their children were legally entitled to attend school or how to begin the process of registering them.

Another five families told Human Rights Watch, mistakenly, that their children could not enroll in Turkish schools because they did not have residency permits, even though the permits are no longer required for registration.

Some of these families based their decision not to register their children at Turkish schools because of stories they had heard in their communities about difficulties others had in doing so, and the lack of adequate information available to them, whether though the schools themselves or through NGOs, made it impossible for them to stay informed about their entitlements.

A UNHCR needs assessment conducted in March 2015 revealed that “many refugee families do not have sufficient information on the procedures that should be followed when they wish to enroll their children in either Turkish schools or Temporary Education Centres.”[160]

An education officer at UNHCR told Human Rights Watch in June 2015 that the agency planned to provide refugee counseling centers in southeastern Turkey with detailed guidance on enrollment procedures for the 2015-2016 school year.[161]

However, the problem is more widespread than just the southeast, although the largest concentrations of Syrian refugees live in that area; Human Rights Watch interviewed Syrian families that had not enrolled their children in school due to lack of information or mistaken information in all five cities visited for this report.

The Turkish government, Syrian interim government, UNICEF, UNHCR, and other bodies should ensure that such guidance is available to Syrians living throughout the country. For example, the international NGO Mercy Corps has set up an information service center called Malumat in downtown Gaziantep, where it offers Syrian refugees pamphlets and counseling on how to access health, education, and legal services.[162] Similarly, the Turkish NGO Association for Solidarity with Asylum-Seekers and Migrants operates “multi-service centers” in Istanbul and Gaziantep that offer information counseling on education in addition to other services to its refugee clients. These services are valuable and should be expanded for the benefit of larger numbers of Syrian refugees.

Overcrowding in Temporary Education Centers

Overcrowding in schools primarily affects Syrian temporary education centers, although it has been an issue in some Turkish government schools since before the Syrian conflict began.[163] According to staff at Mercy Corps, Turkish schools in Gaziantep were already overcrowded and running second shifts before the arrival of Syrian refugees, which made the need for more capacity even more urgent.[164]

A September 2014 assessment by Oxford University’s Refugee Studies Centre found that there were “not enough [temporary education centers] to meet demand” in Gaziantep.[165] Educators in Gaziantep reported “a couple of hundred students on waiting lists for the younger grades.”[166]

Overcrowding is already prevalent in some areas and is likely to become worse due to lack of funding for temporary education centers, which may drive some to close and force their students to attend others nearby or to drop out of school—according to the Oxford study, in 2014 “several schools reported that they are threatened with closure if funding is not secured for the new school year.”[167] In Reyhanli, a city in Turkey’s southern Hatay province that once had 19 operating temporary education centers, all but 3 of the schools temporary education centers had closed due to lack of funding by August 2015.[168]

Exclusion of Syrian Teachers

Syrian educators—like other Syrian workers in Turkey—do not have lawful work permission. They are therefore not entitled to receive salaries for their work in temporary education centers, despite these centers being regulated by MONE; some teachers receive financial “incentives” underwritten by UNICEF or the temporary education centers’ administrations,[169] but many face financial insecurity that makes it harder for temporary education centers to retain good teachers.[170]

One temporary education center director in Istanbul told Human Rights Watch, “We pay teachers from the tuition fees and what we get from the association [that funds the school]. In schools in the south, all the teachers are volunteers.”[171] Another temporary education center director in Istanbul said, “We have 75 teachers. They were all teachers before in Syria; there are more than enough qualified teachers living in Turkey now.”[172]

According to UNICEF:

Syrian refugee teachers constitute an underutilized resource across almost all host countries”.[173] The under-utilization of this resource impacts both access to and quality of education for Syrian refugee children: it “either prevents refugee children from going to school entirely, or means that they will be in larger classes, or attending for a shorter period of time.… The lack of employment opportunities for refugee teachers in host countries contributes to instability.[174]

In response, UNICEF has advocated for “due consideration … to employing Syrian teachers who have the understanding and experience of teaching these children. Turkish authorities, together with partners, need to clearly map who these teachers are and what their qualifications are as a starting point to securing their employment and professional development.”[175]

However, the Turkish government has not yet undertaken the project of identifying and strengthening the use of Syrian refugee teachers, including by offering them legitimate employment opportunities. Instead, the Ministry of National Education clarified its position on Syrian teachers in August 2015, when it issued a statement to correct media reports that it was going to employ Syrian teachers:

The news that there is a study to employ Syrian teachers by our Ministry is in fact a study to determine the Syrian teachers who will voluntarily … help out at the temporary [education] centers [in camps]…. No fee is being given to the Syrian teachers who are serving at the camps on a voluntary basis. Our Ministry is not involved in any other activity regarding Syrian teachers.[176]

IV. The Cost of a Lost Generation

In 2011, Shaza and her family left Damascus after she received threats for organizing protests against the government. When she arrived in Istanbul in 2011, she learned that her son, Omar, was not permitted to attend a Turkish public school because he did not have a residency permit.

There were only a few expensive Arabic-language schools in the area, which the family could not afford. Faced with an education cut short, and no opportunities for lawful employment, Omar, 16, decided to move back to Syria to fight against the Assad government. He was killed in battle shortly afterward. Shaza helped establish a temporary education center after her son left, but it was too late for him to benefit from its services.[177]

Today, Shaza is on the board of directors of the Syrian temporary education center she co-founded in Istanbul. She told Human Rights Watch that her own experience was in part why she realized how important education was to the next generation’s future:

If a person is sick, they can get treatment and get better. If a child doesn’t go to school, it will create big problems in the future—they will end up on the streets, or go back to Syria to die fighting, or be radicalized into extremists, or die in the ocean trying to reach Europe.[178]

Fifteen-year-old Bashar’s experience also illustrates the cost of an education truncated. Bashar had just finished seventh grade in Aleppo when he was forced to drop out of school in 2011 because of regular shelling nearby. His mother explained to Human Rights Watch that he had no opportunity to study in Istanbul, where his family lived, because they needed him to work.

One day he came to us and said he was going back to Syria to fight. We told him ‘no,’ but he was angry with us and crying. He told us he wanted to go and die there, because he saw no future for himself—he hadn’t finished school, and he couldn’t work consistently because he had developed a seizure disorder during the war.

Bashar made it as far as the city of Şanlıurfa on the Turkish side of the border, where his uncle caught up with him and returned him to his family only two days prior to when Human Rights Watch interviewed them. He was unavailable to speak with Human Rights Watch at the time, but his parents acknowledged that his future in Turkey was as bleak as it had ever been. In contrast, his three younger siblings are currently enrolled in a Syrian temporary education center with the help of scholarship funds from a private donor, where they reported they were receiving high marks and making friends.[179]

Bashar’s story highlights the dangers of letting an entire generation of Syrian children miss out on their educations. Prior to the conflict, the primary school enrollment rate in Syria was 99 percent and lower secondary enrollment was 82 percent, with high gender parity.[180] UNICEF has estimated that nearly 3 million Syrian children inside and outside the country are now out of school—demolishing Syria’s achievement of near universal education before the war.[181]

Save the Children has also estimated that if current out-of-school rates among Syrian children inside and outside the country remain consistent, the cost to Syria’s post-war economy will be almost $2.18 billion a year due to lost wages.[182]