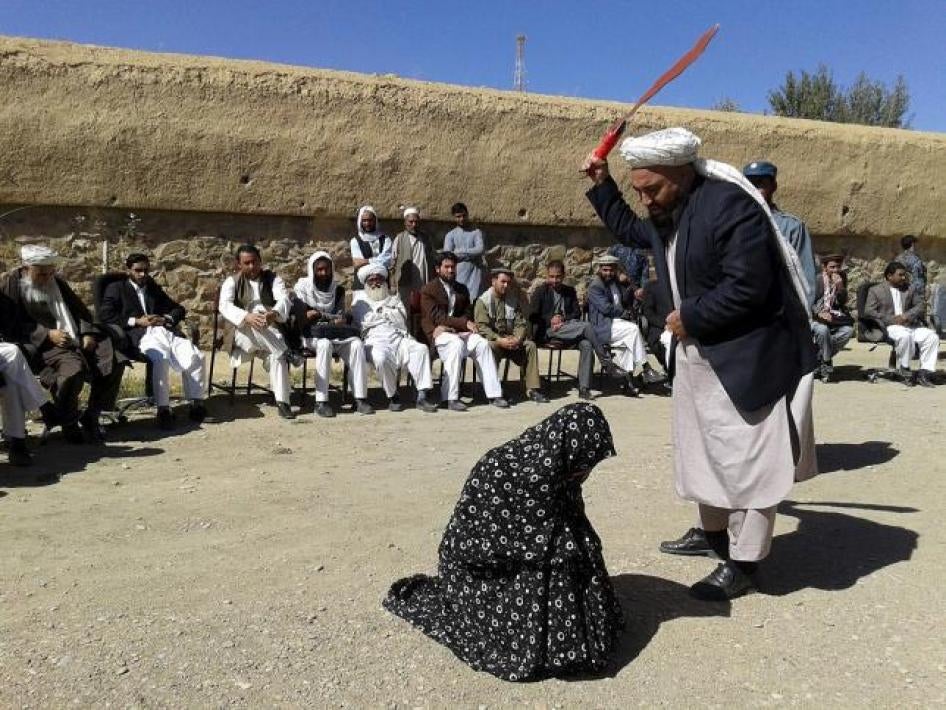

It’s a scene we associate with the Taliban. A woman covered head to toe in a flowing veil, huddled on the ground before a man in a turban. His right arm is raised, in motion, holding a lash, a second away from bringing it down on her. An audience of men – only men – sit in a circle around them. They have chairs – a nod to their comfort while they watch what may be intended as a cautionary lesson, or spectacle.

This is not the Taliban. This photo emerged on September 1, and reportedly shows the lashing of a woman named Zarmina, 22, who was arrested with a man named Ahmad, 21, several weeks ago in Afghanistan’s Ghor province. The two were accused of zina, or sex outside of marriage, which under Afghan law is a crime carrying a sentence of 5 to 15 years in prison. The two were sentenced to 100 lashes each by a court – not a Taliban tribunal, not a convening of elders, but a formal court of law that is part of the same Afghan government that the international community has been working to strengthen and legitimize since the fall of the Taliban government in 2001. The punishment of lashing is illegal, as it is not authorized by law, but Afghan courts hand out corporal punishment with sufficient regularity that district judges have been known to keep a lash hanging in their office.

Sex between two consenting adults should never be a crime. But even more horrifyingly, a conviction for zina in Afghanistan is often based on the shakiest of evidence. When I interviewed dozens of women and girls imprisoned for zina and reviewed their cases, I learned that judges hand down harsh sentences based on women having left the home without permission, having been alone in the presence of a man who is not a relative, on malicious statements from angry and abusive husbands and fathers, and on abusive “virginity exams” – vaginal examinations that are medically meaningless.

On September 5, donor governments will convene in Kabul for a “senior officials meeting” to agree on a road map for international aid to Afghanistan for the next four years. This photo should be one more reminder of the extent to which the Afghan government continues to violate human rights, especially those of women. Ahead of the conference, President Ashraf Ghani has negotiated hard with foreign donors to reduce the human rights expectations they will place on his government. Instead, donors need to be much tougher about keeping rights at the top of the agenda.

They owe it to all of Afghanistan’s Zarminas and Ahmads.