(N’Djamena, Chad) – “Even after I escaped from them and live far away from my village, I am still afraid,” a 17-year-old girl who escaped from Boko Haram last year told us in June. “I think of death many times.”

The shocking abduction of 276 girls from a secondary school in Chibok, Nigeria, last April 14 attracted world attention to the brutality of the Boko Haram Islamist insurgency. One year on, the news remains bleak. Boko Haram still holds 219 of the schoolgirls and hundreds of other abducted women and girls, many forced to convert to Islam and “marry” their captors. As recently as March, media reported that Boko Haram fighters abducted and fled with more than 400 women and children in the northern town of Damasak. And many of the 57 escaped Chibok schoolgirls and other escapees now lead lives of despair.

Many questions remain: Are the Chibok girls in captivity still alive? Where are they? Why have they and others not been rescued? Why have no Boko Haram commanders responsible for the abduction been arrested and brought to justice?

Following the Boko Haram attack, parents of the schoolgirls and others protested what they saw as the Nigerian government’s slow and dithering response. Within weeks a twitter campaign, #BringBackOurGirls, went viral, forcing the Nigerian government to pay attention.

But countless tweets and many empty promises later, the failure of Nigeria’s security forces to rescue any of the Chibok schoolgirls remains a heartbreaking fact. The 57 Chibok girls who have returned either escaped or were released by their captors – none have been rescued.

Those held captive by Boko Haram face appalling abuses. Shortly after the Chibok abductions, Human Rights Watch interviewed 30 women and girls, including 12 Chibok schoolgirls, who had managed to escape their captivity. Those who escaped from Boko Haram camps told us how the insurgents forced them to convert to Islam, forcibly “married” them to Boko Haram fighters, some of whom were decades older, and raped them.

Boko Haram forced some of the abducted women and girls to participate in military operations, including as suicide bombers. In December, – a suicide bomber was identified as a 16-year-old who was abducted in November 2013. A former captive tearfully told us that she recognized the bomber, whose attack with another female bomber killed five people, as a fellow captive.

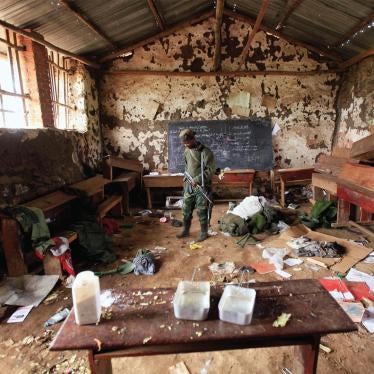

While a number of Chibok schoolgirls have returned to school on scholarships and received psychosocial counseling, they are the exception. Most former captives have received little or no help and very few have returned home. Chibok and other villages and town in Borno state continue to be ravaged by repeated Boko Haram attacks.

The culture of silence, stigma and shame around sexual abuse in the religiously conservative areas of northern Nigeria have added to the trauma and deterred many from seeking help. One girl said she could not remain in Chibok because neighbors referred to her and other escapees as “Boko Haram wives.” The stigma eventually drove her to live in a shelter far from her home where she could live anonymously.

In January, the African Union endorsed a multinational task force to fight Boko Haram. Nigerian security forces aided by forces from Cameroon, Chad, and Niger have since dislodged insurgents from some areas of Nigeria’s northeast. These military operations against Boko Haram should make protecting civilians from further Boko Haram attacks, stopping abductions, and rescuing those held captive a priority.

But military action alone will not address the tragic situation unfolding in northeastern Nigeria. Nigeria’s newly elected government should ensure that abuses by its own security forces in operations against Boko Haram are investigated and those responsible held to account. The government also needs to ensure that medical treatment, counselling, opportunities for education and livelihoods is provided to former captives who have escaped Boko Haram’s brutality and who want to rebuild their shattered lives.

“My father tries,” the 17-year-old girl told us. “He encourages me to forget everything, but it is not easy for me. I have terrible dreams at night.”

Nigeria’s women and girls deserve better. On the anniversary of the Chibok mass abduction, our collective outrage should not subside. Not only should we continue to support efforts to #BringBackOurGirls from Chibok and other villages and towns that have been attacked, but we should also support those who have escaped. Maybe it’s time for a new hashtag: #HelpTheEscaped.

Mausi Segun is the Nigeria researcher at Human Rights Watch and Samer Muscati is a Human Rights Watch women’s rights researcher working with her.