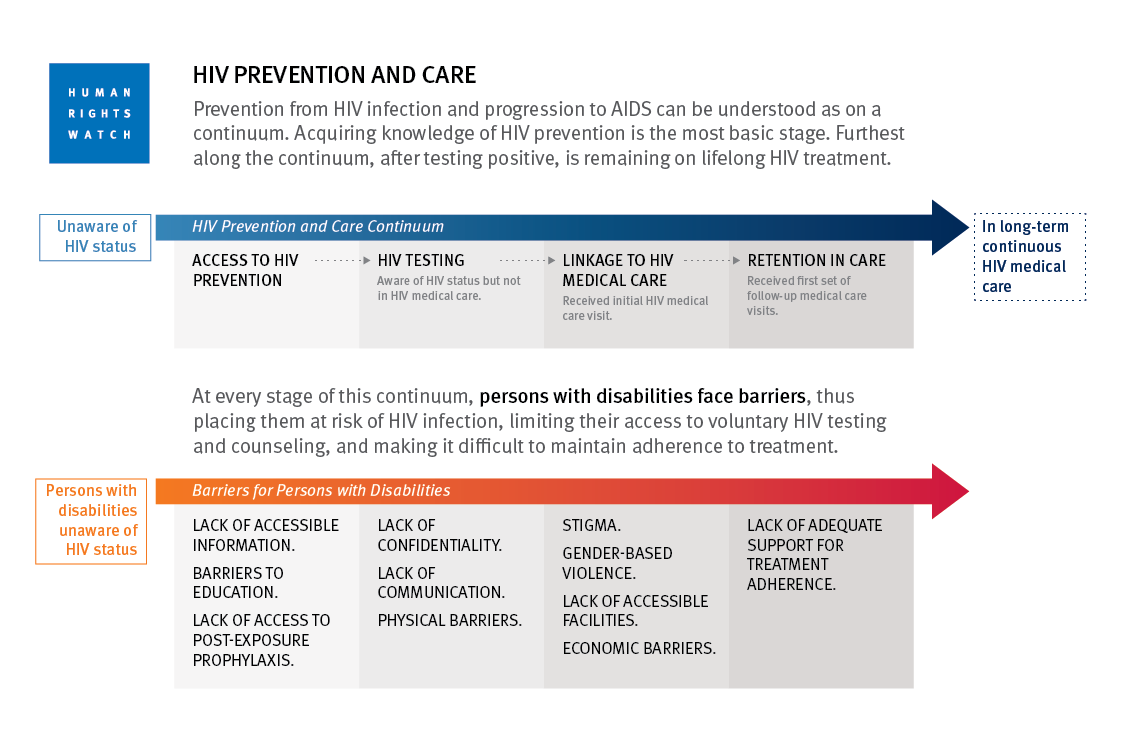

(Lusaka) – The nearly two million people with disabilities in Zambia face significant barriers to HIV prevention, testing, and treatment, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. While the Zambian government has made considerable progress scaling up its response to HIV generally, few programs are accessible to people with disabilities and social stigma prevents their access to HIV services on an equal basis with others.

The 80-page report, “‘We Are Also Dying of AIDS’: Barriers to HIV Services and Treatment for Persons with Disabilities in Zambia,” documents the obstacles faced by people with disabilities in both the community and healthcare settings. These include pervasive stigma and discrimination, lack of access to inclusive HIV prevention education, obstacles to accessing voluntary testing and HIV treatment, and lack of appropriate support for adherence to antiretroviral treatment. The report also describes the sexual and intimate partner violence women and girls with disabilities face, and the need for the government and international donors to do more to ensure inclusive and accessible HIV services.

“Across the continuum of care – from education to testing to treatment – people with disabilities in Zambia face hurdle after hurdle,” said Rashmi Chopra, Sandler fellow at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. “As a regional leader in developing and expanding comprehensive HIV services, Zambia should remove these barriers and become a model for inclusion of people with disabilities.”

The report is based on more than 200 interviews in Zambia with people with disabilities, parents of children with disabilities, special education teachers, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, government officials, healthcare workers, and others.

More than one in 10 adults in Zambia is living with HIV, and a similar number of people have a disability. People with physical, sensory, psychosocial, and intellectual disabilities may be more vulnerable to HIV infection than other Zambians due to their lower education and literacy levels, greater poverty, and greater risks of physical and sexual abuse.

People with various disabilities told Human Rights Watch that they are often viewed as asexual and face negative attitudes about their right to marry and have children. Those responses sometimes restrict their access to HIV prevention, testing, or treatment services.

Yvone L. (a pseudonym), who has a physical disability, told Human Rights Watch, “When you go for VCT [voluntary HIV counseling and testing], you are looked up and down, people say, ‘Why should you be in the line? Who could give you HIV?’ They don’t expect disabled women to be sexually active.”

Children with disabilities are unable to access HIV prevention information on an equal basis with other children. Discrimination within the family, admission barriers, and lack of physical accessibility keep many children with disabilities out of school, where they might receive HIV prevention information. Even when children are able to attend school, children with disabilities are often excluded from programs providing HIV information, or do not get materials that are accessible to them.

Similarly, adults with disabilities often cannot access general HIV information disseminated through print and mass media because of the lack of materials produced in simplified formats, braille, large print, or with sign language symbols.

Women and girls with disabilities have high rates of sexual and intimate-partner violence, which increases their risk for HIV infection. The vulnerability of women and girls with disabilities is compounded because they lack equal access to information about gender-based violence, HIV prevention, and social protection services.

People with disabilities told Human Rights Watch that they often are unable to get effective pre- and post-HIV testing counseling because of inadequate training of healthcare workers on how to communicate with and address the concerns of people with disabilities. Once they are on antiretroviral treatment, people with disabilities often depend on the availability of a family member or friend for mobility or communication assistance to keep up with scheduled appointments.

When this support is not available, accommodations are rarely made for their circumstances, such as rescheduling appointments or providing a longer supply of medicine. Instead, healthcare workers often label people with disabilities “defaulters” if they miss appointments, requiring them to have more frequent appointments and limiting their supply of medicine.

Zambia has ratified a number of international and regional human rights treaties including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which obligates governments to provide people with disabilities the same range, quality, and standard of free or affordable health care and programs as provided to others, including population-based public health programs. This means that people with disabilities should be able to access HIV services on an equal basis with others.

Zambia’s 2012 Persons with Disabilities Act directs the government to provide equal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare and public health programs. The Zambian government recognizes people with disabilities as a vulnerable population at risk for HIV, yet it has not put into effect specific services and strategies to provide inclusive HIV services.

International donors and United Nations agencies are aware of the lack of inclusive and targeted HIV services for people with disabilities in Zambia. However, they also have not done enough to ensure that funding for HIV services is allocated without discrimination and equitably benefits people with disabilities.

The Zambian government and international donors should develop disability-specific HIV services and ensure accessibility and non-discrimination within mainstream HIV services, Human Rights Watch said. The government and donors should also initiate research on HIV risk factors among people with disabilities.

“Zambia deserves credit for recognizing people with disabilities as a high-risk population for HIV,” Chopra said. “Now some real changes are needed to include people with disabilities in Zambia’s HIV response.”