Millions of Indians suffering chronic pain will get better access to pain medicines following changes in India’s drug law, Human Rights Watch said today. On February 21, 2014, the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of parliament, approved amendments to the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (the Drug Act) that the lower house had approved a day earlier.

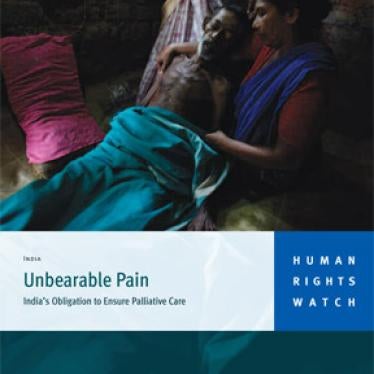

The amendments eliminate archaic rules that obligated hospitals and pharmacies to obtain four or five licenses, each from a different government agency, every time they wanted to purchase strong pain medicines. As Human Rights Watch documented in a 2009 report, “Unbearable Pain: India's Obligation to Ensure Palliative Care,” this resulted in the virtual disappearance of morphine, an essential medicine for strong pain, from Indian hospitals, including from most specialized cancer centers.

“The revised Drug Act is very good news for people with pain in India,” said Diederik Lohman, senior health researcher at Human Rights Watch. “These changes will help spare millions of people the indignity of suffering needlessly from severe pain.”

Patients who experience severe pain without access to adequate treatment face enormous suffering. Like victims of torture, these patients have often told Human Rights Watch that the pain was intolerable and that they would do anything to make it stop. Many said that they saw death as the only way out and some said they had become suicidal.

The amendments to the Drug Act give the central government authority to regulate so-called “narcotic drugs,” require a single license to procure morphine and other strong opioid medications, and charge one government agency, the state drug controller, with enforcement. The government introduced the amendments to the Drug Act in 2012.

Over the last 15 years, India’s central government had repeatedly encouraged the country’s states and territories to counter the Drug Act’s detrimental effects on the availability of pain medicines. In 1998, it recognized that the law had caused “undue sufferings and harassment” to cancer patients and recommended simplified regulations for obtaining morphine tablets. However, because the law leaves regulation of narcotic drugs to India’s states and territories, the central government could not force them to carry out the recommendation. Only 17 of India’s 35 states and territories had introduced the simplified procedure.

In the seven years following the introduction of the Drug Act in 1985, morphine use in India plummeted by 97 percent. Human Rights Watch estimated that the amount of morphine India used in 2008 was sufficient for just 4 percent of patients with advanced cancer who required it.

The World Health Organization and the Indian government consider morphine an essential medicine for the treatment of strong pain from cancer and other illnesses.

In January, the World Health Organization’s board adopted a groundbreaking resolution calling on countries to integrate palliative care, a health service that seeks to improve the quality of life in people with life-limiting illnesses, into their health systems. It recommended, among other steps, that countries review their drug regulations and amend them if they were found to impede access to pain medicines.

In 2011, the Medical Council of India recognized palliative care as a specialization of medicine, paving the way for improved training of healthcare workers. In 2012, the Ministry of Health and Family Affairs approved a national palliative care strategy.

“India had made significant progress in improving the availability of palliative care in recent years,” Lohman said. “But the new revisions to the Drug Act remove one of the biggest remaining barriers to dignified end-of-life care in India.”