In January, years of joint advocacy by Human Rights Watch and Indian palliative care groups culminated in the Medical Council of India recognizing palliative care as a specialization of medicine and approving an MD Palliative Care program. Over time, this decision will lead to a significant increase in the number of physicians trained to prevent needless suffering from life-threatening or debilitating illnesses.

To date, only 5 out of some 300 medical colleges in the entire country have integrated any instruction into their curricula on palliative care—treatment which focuses on improving patients’ quality of life, including by preventing or reducing pain. Consequently, the vast majority of medical doctors in India are unfamiliar with even the most basic tenets of palliative care. In many cases, patients are denied treatment and suffer severe pain, often for weeks or months on end. Many such patients told Human Rights Watch that their suffering was so severe that they wanted to die. Some said they had contemplated or attempted suicide.

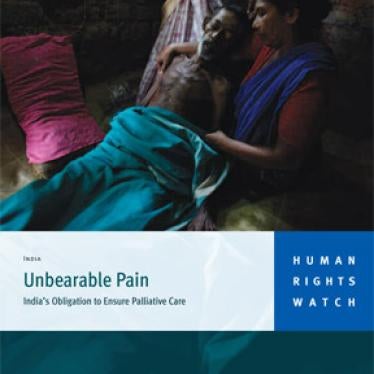

Sherin, a construction worker in Kerala, experienced severe pain after a wall collapsed on him, causing spinal cord injury. He told Human Rights Watch that his doctors did not treat his pain: “I was told that I would be OK…. The doctors said that the pain would go away [by itself]. There was no need to medicate it. I was screaming all through the night.” With inexpensive medications, doctors could have provided Sherin with significant, if not complete, relief from his pain. He is one of the estimated 7 million people who require palliative care services in India each year.

Human Rights Watch began documenting the extreme suffering of patients who did not have access to appropriate pain treatment in 2008. We interviewed more than 100 people across India, including patients with advanced life-threatening or debilitating illnesses, healthcare experts and volunteers, and government health officials. Our research highlighted how the lack of training for healthcare workers perpetuates this mass suffering, as many doctors simply do not know how to treat patients with severe pain and other symptoms.

In October 2009, we published our findings in a groundbreaking report. With our local partners, Pallium India and the Pain Relief and Palliative Care Society of Hyderabad, we brought our findings to the Medical Council of India, the institution that establishes medical training qualification standards. During this meeting, we advocated for better palliative care instruction for physicians. In follow-up, we worked with Dr. M.R. Rajagopal of Pallium India. Dr. Rajagopal reached out to several Indian medical universities to create detailed proposals for how doctors specializing in palliative care should be trained. These proposals were submitted to the Medical Council of India.

At the same time, Human Rights Watch began advising the plaintiffs in a case on palliative care still being heard by India’s Supreme Court on how international standards could be used to strengthen their case. This landmark case, brought by the Indian Association of Palliative Care and others, would oblige the government to introduce palliative care training for healthcare providers and to eliminate drug laws that impede the availability of essential pain medicine.

Shortly after its representatives attended one of the case’s hearings, the Medical Council of India added the new training specialization in palliative care.

Several months after Sherin sustained his injury, palliative care volunteers found him, partially paralyzed and still reeling in pain, at his local hospital. After enrolling him in their program, doctors put Sherin on pain medications for the first time and gave him exercises that are helping him improve his mobility.

Sitting in his stick hut with banana leaf roof, Sherin told Human Rights Watch that palliative care had changed his life: “I went through hell,” said Sherin. He added: “Now I have something to look forward to.” The newly approved palliative care specialization means that there is now hope that many more people will have access to the restorative treatment that changed Sherin’s life.