A landmark report by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) of the Department of Justice issued on Wednesday, May 1, 2013, concludes that the compassionate release program of the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is badly mismanaged. According to the report, the BOP central office has failed to set clear and consistent standards for compassionate release, does not monitor implementation of the program, does not know how many prisoners seek compassionate release in any given year, nor how long it takes to reach a final decision in their cases. It operates the program in an “ad hoc” way that ill serves prisoners and the country.

Compassionate release for federal prisoners is authorized in federal law when changed circumstances make continued imprisonment senseless and inhumane. Congress in 1984 gave federal courts authority to grant compassionate release for “extraordinary and compelling” reasons, such as a prisoner's imminent death or serious incapacitation. But they cannot do so absent a motion by the Bureau of Prisons, which rarely submits the prisoners’ cases to the courts. By failing to submit cases for compassionate release, prison officials prevent judges from deciding, as Congress intended, when compassion requires a sentence reduction.

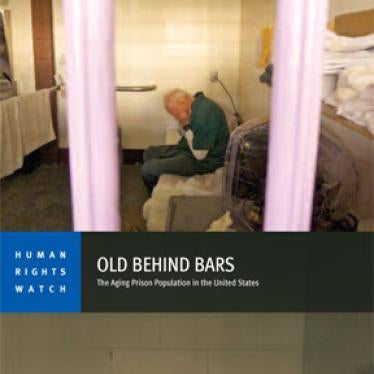

The OIG findings confirm those made by Human Rights Watch and FAMM in a jointly published report last November, The Answer is No: Too Little Compassionate Release in US Federal Prisons. In a prison population of 218,000 prisoners, the largest in the country, an average of only two dozen prisoners receive compassionate release annually. As a result, dying or seriously debilitated prisoners remain needlessly incarcerated. BOP officials not only have ignored their requests to be released to the care of their families, but have also ignored the significant opportunity compassionate release offers for reducing the size of the dangerously overcrowded federal prison system and reining in its runaway medical expenses.

According to the OIG, the BOP has failed to:

• Establish appropriate medical and non-medical criteria for compassionate release consideration and has not adequately defined “extraordinary and compelling” circumstances that might warrant release;

• Put in place timeliness standards at each step of the internal BOP process for reviewing prisoner compassionate release requests;

• Put in place procedures to inform inmates about the compassionate release program;

• Have a system to track all compassionate release requests, the timeliness of the review process, or whether decisions made by institution and regional office staff are consistent with each other or with BOP policy.

As a result of these failures, many potentially eligible prisoners never receive the consideration their situations warrant. About 13 percent die while waiting final word on their requests.

The Office of the Deputy Attorney General (ODAG) in the Department of Justice also plays a role in limiting compassionate release. As both the OIG and the Human Rights Watch-FAMM report documented, in the past the ODAG has opposed rules that would have expanded compassionate release beyond a narrow category of the most dire medical cases, but the ODAG has rejected compassionate release even in such cases. For example, the OIG reports that in 2006 the ODAG opposed the early release of a prisoner serving a life sentence for drug trafficking who was in a near vegetative state following a massive stroke; the prisoner remains incarcerated, although he is paralyzed down the right side of his body, unable to speak, and requires total assistance with the activities of daily living.

Human Rights Watch notes that the OIG’s research was extremely thorough and impartial. We regret, however, that the OIG did not explore the reasons why the BOP declines to make motions for early release even in cases in which there is no question the prisoner is close to death or utterly incapacitated. In our report, Human Rights Watch and FAMM revealed that wardens — who make the initial, and what often proves to be the final, decision on prisoner requests — will refuse requests based on their own beliefs about whether a prisoner might endanger public safety if released, or whether the prisoner has served enough time. These are the very criteria Congress instructed judges (not wardens) to take into account in making early release decisions. This is troubling enough, but perhaps even worse, the BOP has permitted wardens to take into account such factors without ever instructing them on how to properly and responsibly exercise their discretion — much less assessing how they in fact have done so. In one case mentioned in our report, a warden declined on public safety grounds the request for compassionate release of a prisoner convicted of a sex offense and now permanently paralyzed from the neck down. When questioned how the prisoner could threaten harm to anyone, she agreed he could not, but felt that she had to think about how the victim and her family would feel if he were sent home.

To its credit, the BOP has acknowledged the merits of the OIG’s critiques and has agreed to follow up on the OIG’s recommendations to improve the management, tracking, and monitoring of the compassionate release program and to develop measures for assessing its impact on the prison system’s budget and population size, particularly if it were expanded.

Good intentions, however, are rarely enough. Human Rights Watch urges congressional hearings and more vigorous congressional oversight to ensure the BOP moves rapidly forward to correct and rebuild the ad hoc and badly mismanaged program described by both the OIG and the Human Rights Watch-FAMM reports.