(New York) – Armed opposition groups have subjected detainees to ill-treatment and torture and committed extrajudicial or summary executions in Aleppo, Latakia, and Idlib, Human Rights Watch said today following a visit to Aleppo governorate. Torture and extrajudicial or summary executions of detainees in the context of an armed conflict are war crimes, and may constitute crimes against humanity if they are widespread and systematic.

Opposition leaders told Human Rights Watch that they will respect human rights and that they have taken measures to curb the abuses, but Human Rights Watch expressed serious concern about statements by some opposition leaders indicating that they tolerate, or even condone, extrajudicial and summary executions. When confronted with evidence of extrajudicial executions, three opposition leaders told Human Rights Watch that those who killed deserved to be killed, and that only the worst criminals were being executed.

“Declarations by opposition groups that they want to respect human rights are important, but the real test is how opposition forces behave,” said Nadim Houry, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “Those assisting the Syrian opposition have a particular responsibility to condemn abuses.”

Military and civilian Syrian opposition leaders should immediately take all possible measures to end the use of torture and executions by opposition groups, including condemning and prohibiting such practices, Human Rights Watch said. They should investigate the abuses, hold those responsible to account in accordance with international human rights law, and invite recognized international detention monitors to visit all detention facilities under their control. Initiatives to have armed opposition groups adopt and enforce codes of conduct that promote respect for human rights and international humanitarian law should be encouraged.

Human Rights Watch presented its research findings and detailed recommendations in meetings with opposition leaders in northern Aleppo in August and in a letter sent to several opposition leaders on August 21, 2012. In a written response, the Military Council for the Aleppo Governorate said that, in light of the findings, it had reiterated its commitment to humanitarian law and human rights to Free Syrian Army (FSA) groups, that it was in the process of establishing special committees to review detention conditions and practices, and that it would hold responsible those who act “contrary to the guidelines.”

Countries financing or supplying arms to opposition groups should send a strong signal to the opposition that they expect it to comply strictly with international human rights and humanitarian law, Human Rights Watch said.

Human Rights Watch documented more than a dozen extrajudicial and summary executions by opposition forces. Two FSA fighters from the Ansar Mohammed battalion in Latakia told Human Rights Watch, for example, that four people had been executed after the battalion stormed a police station in Haffa in June 2012, two immediately and the others after a trial.

Six of 12 detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch in two opposition-run detention facilities said that FSA fighters and officials in charge of detention facilities had tortured and mistreated them, in particular by beating them on the soles of their feet. Abuse appeared to be more prevalent during the initial stages of detention, before the detainees were transferred to civilian opposition authorities.

Because of inconsistencies in their accounts and visible injuries consistent with torture, Human Rights Watch has reason to believe that FSA fighters and prison authorities had also tortured or mistreated at least some of the six detainees who denied during their interviews that they had been abused.

“Sameer,” whom the FSA arrested in the beginning of August, told Human Rights Watch.

The FSA fighters who caught me first brought me to their base. I spent a night there, together with one other prisoner. They beat me a lot, with a wooden stick, on the soles of my feet. It lasted for about two hours. First, I refused to confess, but then I had to. Once I confessed, they stopped beating me.

Human Rights Watch has also reviewed more than 25 videos on YouTube in which people reportedly in the custody of armed opposition groups show signs of physical abuse. Human Rights Watch cannot independently confirm the authenticity of these videos.

The head of the Aleppo Governorate Revolutionary Council told Human Rights Watch that the authorities do not execute or torture detainees, but that beating detainees on the soles of the feet was “permissible” because it did not cause injuries. When Human Rights Watch explained that beating on the soles of the feet constitutes torture and is unlawful according to international law, he said that he would provide new instructions to FSA fighters and those in charge of detention facilities that such beating was not permitted.

“Time and again Syria’s opposition has told us that it is fighting against the government because of its abhorrent human rights violations,” Houry said. “Now is the time for the opposition to show that they really mean what they say.”

Local opposition authorities told Human Rights Watch that they have appointed judicial councils that review accusations against detainees and issue sentences. In some towns, these judicial councils relied exclusively on Sharia law. In other towns, the judicial councils relied on Sharia law for civil matters, but still relied on Syrian criminal law for criminal matters.

Descriptions of the trials by detainees and members of the judicial councils indicate that the trials did not meet international due process standards, including the right to legal representation and the opportunity to prepare one’s defense and challenge all the evidence and witnesses against them.

All armed forces involved in the hostilities, including non-state armed groups, are required to abide by international humanitarian law. The FSA, at least in the areas where Human Rights Watch has conducted its research, appears to be capable of ensuring respect for international humanitarian law by its forces given its level of organization and control. A number of countries are providing armed opposition groups in Syria with financial and military support. Interviews with Syrian opposition activists as well as media reports indicate that Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey are actively assisting a number of armed groups. The United States, the United Kingdom, and France, have also pledged non-lethal aid to opposition groups. Human Rights Watch urged countries assisting opposition groups to condemn publicly the human rights and humanitarian law abuses by those groups.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly documented and condemned widespread violations by Syrian government security forces and officials, including extrajudicial executions and other unlawful killings of civilians, enforced disappearances, use of torture, and arbitrary detentions. Human Rights Watch has concluded that government forces have committed crimes against humanity.

The United Nations Security Council should refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC), which would have jurisdiction to investigate violations by both government and opposition forces, Human Rights Watch said. Russia and China should support such a referral.

“An ICC referral would give the ICC jurisdiction to investigate crimes committed by both the government and the opposition,” Houry said. “This is one measure that all Security Council members, including Russia, should find it easy to agree on if they are truly concerned about the violations committed in Syria.”

For more information on Human Rights Watch findings and the requirements under international law please, see the below text.

Torture and Ill-treatment of Detainees

During the Human Rights Watch research mission to the Aleppo governorate in August, the Aleppo Governorate Revolutionary Council, the Aleppo Governorate Military Council, and opposition authorities Al-Bab, Tel Rifat, and Maare granted Human Rights Watch access to detention facilities under their jurisdiction. Opposition leaders in Azaz, a town on the Turkish-Syrian border, denied Human Rights Watch access to their detention facility.

Six detainees in opposition custody out of the 12 interviewed told Human Rights Watch in private interviews that they had suffered abuse that would amount to torture or other unlawful ill-treatment by armed opposition forces during the initial stages of their detention, in temporary holding facilities. The torture included beatings, some on the soles of the feet or with cables, and kicking.

A detainee who had been held in a school told Human Rights Watch that FSA fighters there had beaten him regularly for 25 days before he was transferred to the detention facility where Human Rights Watch interviewed him:

They beat me every two or three days. They tied me to a cross with my face down. Five guys started beating me, using cables. The first time they hit me for about an hour. The third time they hit me from early in the morning until noon. They also hit me in the face. The FSA fighters wanted me to confess to having killed several people with a knife. Eventually I confessed because they beat me, although I have not killed anybody. The FSA fighters said that they would kill me if I said something about the torture.

Bruises on the detainee’s body were consistent with his account and still visible several weeks after he said the beating had taken place. The detainee also showed Human Rights Watch a blackened fingernail on his right hand, which he said resulted from trying to protect himself from the beating.

Another detainee said that FSA fighters had beaten him when he was held in a school for four or five hours before he was transferred to the detention facility where Human Rights Watch interviewed him:

They accused us of being shabeeha (pro-government militia). They beat us and hit us with sticks. We were blindfolded so I don’t know exactly how many they were, but they were many.

The detainee had a bruise under his right eye, a large bruise on his right shoulder, and smaller bruises on his right shoulder and back.

The detainees told Human Rights Watch that they did not know the name or exact locations of the schools where they had been initially held.

Human Rights Watch received reports of torture and ill-treatment in the main Free Syrian Army base in Aleppo city, which also served as a temporary holding facility. While the detainees we interviewed did not know the exact location where they had been initially held, FSA fighters involved in detentions and other witnesses told Human Rights Watch that detainees were usually first transferred to this base in Aleppo. Three people interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been at the base in August said that they had heard and seen ill-treatment of people detained and brought to this FSA base.

According to information received by Human Rights Watch, the FSA moved its main base to a new location in August because the base came under attack.

In meetings with Human Rights Watch, local opposition authorities in Aleppo acknowledged that they had received reports about ill-treatment of detainees and that these reports had prompted the opposition authorities to establish two central detention facilities. Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said, however, that beating, kicking, and other forms of ill-treatment continued at the FSA base in Aleppo even after the two central detention facilities had been established.

Human Rights Watch also documented torture and ill-treatment in the Maare detention facility, one of the recently established central detention facilities. Two of the detainees there interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had been subjected to severe ill-treatment during interrogations. The treatment they described would appear to amount to torture given that it was the deliberate infliction of severe pain for a specific purpose.

“Sameer,” whom the FSA arrested in the beginning of August, told Human Rights Watch:

The FSA fighters who caught me first brought me to their base. I spent a night there, together with one other prisoner. They beat me a lot, with a wooden stick, on the soles of my feet. It lasted for about two hours. First, I refused to confess, but then I had to. Once I confessed, they stopped beating me.

Here [in Maare prison] they interrogated me as well. They beat me again on the soles of my feet, with a stick and a cable, for about 30 minutes. I was on my back, with my feet up in the air, tied. I didn’t deny the charges, but they wanted me to repeat my confession.

Three other detainees said that they had not been subjected to ill-treatment in the Maare prison. These were the first prisoners in Maare Human Rights Watch was allowed to interview in private, after the administration there initially refused. In all three interviews, the detainees appeared apprehensive and reluctant to provide details about their treatment. Human Rights Watch therefore suspects that they had been instructed by those in charge not talk about their experiences. After Human Rights Watch researchers raised this issue with the administration of the facility, the researchers were allowed to talk to two randomly selected detainees, both of whom complained freely of ill-treatment.

Human Rights Watch found that opposition commanders in several places condoned beating detainees on the soles of the feet, a torture method frequently used also by Syrian government forces that is sometimes called falaqa. The head of the Aleppo Governorate Revolutionary Council told Human Rights Watch that the opposition authorities do not execute or torture detainees, but that beating detainees on the soles of the feet was “permissible” because it did not cause injuries. When Human Rights Watch explained that beating on the soles of the feet constitutes torture and is unlawful according to international law, he said that he would provide new instructions to FSA fighters and those in charge of detention facilities that such beating was not permitted.

Two FSA fighters from the Ansar Mohammed battalion in Latakia told Human Rights Watch that they had detained about 40 people after storming a police station in Haffa in June. They said that the battalion leadership and the sheikhs who form the judicial council had provided instructions for treatment of the detainees:

The sheikhs instructed us that we should not severely torture the detainees. We are only allowed to use falaqa. We can’t hit detainees in the face, on their back, or any other places. Just on the soles of their feet, and only for a total of one hour per day. We use it to make them confess. It usually works.

Human Rights Watch also requested permission from local opposition authorities in Azaz to visit their detention facility and to interview detainees in private. Their refusal raises concern about the treatment of detainees there. Compounding this concern is that members of the Azaz political and military offices provided inconsistent accounts about how many detainees they have in their custody, how long they have been there, and how the staff decides whom to send to the central detention facility in Maare.

Extrajudicial Executions

Human Rights Watch has documented 12 cases of extrajudicial and summary executions by opposition forces.

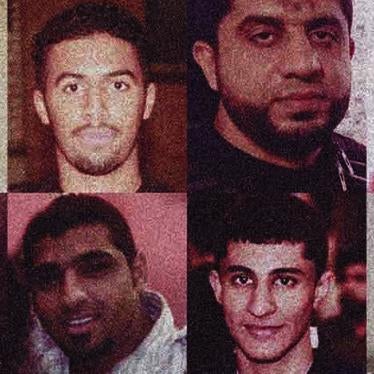

On July 31, members of the al-Barri family in Aleppo allegedly killed 15 FSA soldiers in clashes in the city of Aleppo. A video posted on YouTube the same day shows people who appear to be FSA fighters executing four members of the al-Barri family.

Two members of the Aleppo Governorate Revolutionary Council confirmed the execution of the four, but claimed that a local judicial council had held a trial and sentenced the four men to death. One of the council members said that 21 other members of the family had been released. A revolutionary council member told Human Rights Watch that there were no records from the trial.

Human Rights Watch has not been able to establish the exact nature of the judicial proceedings or whether they actually took place. However, it would appear impossible that the men received a fair trial by a regularly constituted court considering the circumstances and the haste with which they were tried and executed. Human Rights Watch therefore concluded that these should be considered summary executions.

Human Rights Watch saw another member of the al-Barri family in FSA custody during the funeral procession in Tel Rifat for eight FSA fighters from Tel Rifat who were reportedly killed in the Aleppo city clashes with the al-Barri family on July 31. Local FSA military authorities assured Human Rights Watch that the detainee would be treated well and transferred to the civilian authorities who were in charge of detainees in Tel Rifat. However a witness who attended the burial told Human Rights Watch that other FSA fighters brought the detainee to the graveyard at gunpoint, at which point the witness left.

When he returned later, he saw nine recent graves, although only eight fighters had been buried. Despite repeated requests in the following days by Human Rights Watch to see the detainee, opposition authorities refused. Opposition members refused to explain to Human Rights Watch what had happened to the detainee, but they did not deny allegations that he had been executed.

Two FSA fighters from the Ansar Mohammed battalion in Latakia told Human Rights Watch that four people had been executed after the battalion stormed a police station in Haffa in June 2012.

We killed the two snipers on the roof right away [after they were captured], without any trial. Everybody saw that they had been shooting at us and killing FSA fighters so there was no need for a trial. Two other people detained in the police station were accused of rape and murder. There was a month-long trial and they were also sentenced to death. The girl who was raped identified one of them. They were both shot.

As with the trial of the members of the al-Barri family, Human Rights Watch has not been able to establish the exact nature of the judicial proceedings but the evidence strongly suggests it did not meet international standards. One of the FSA fighters told Human Rights Watch: “We didn’t torture the rapist, but we used the falaqa on him. He had already confessed, but we hit him as a punishment.”

An opposition leader from the town of Der Hafer also told Human Rights Watch that FSA fighters there executed three officers in late August after they were captured, but had no other details about the execution.

Human Rights Watch has also reviewed more than 15 videos on YouTube that appear to show extrajudicial executions of people in the custody of armed opposition groups. The most recent such video was posted on September 10 and shows what appear to be the extrajudicial executions of 21 government soldiers in the city of Aleppo. Human Rights Watch cannot independently confirm the authenticity of these videos.

Human Rights Watch opposes the use of death penalty in all circumstances.

Fair Trial Abuses

Local opposition authorities told us that they have appointed judicial councils that review accusations against detainees and issue sentences. In some towns, these judicial councils relied exclusively on Shariaor Islamic law. In other towns, the judicial councils relied on Sharia for civil matters, but still relied on Syrian criminal law for criminal matters.

Human Rights Watch takes no position for or against Sharia or any other system of religious law, but is concerned about preventing and ending human rights abuses in all countries, whatever their basis or legal justification. Under international humanitarian law, only a regularly constituted court meeting international fair trial standards is allowed to hand down sentences.

Under human rights law, certain rights are considered so fundamental that they may not be suspended, even during an emergency. These rights include not only the prohibition on torture and other ill-treatment, but the prohibition on arbitrary detention, specifically the need for judicial review of detention, and the guarantees of a fair trial. Thus, even during an emergency, only courts of law, made up of independent and impartial judges, can try and convict, and people can only be tried for crimes that are set out clearly in the national or international law – and that were crimes at the time of the offense. They also have the right to legal representation and to an opportunity to prepare their defense and challenge all the evidence and witnesses against them.

A member of the Aleppo revolutionary council told Human Rights Watch the judicial councils did not hand down death sentences. This claim, however, is contradicted by the supposed trial and summary execution of four members of the al-Barri family. An international journalist who traveled to Aleppo governorate also told Human Rights Watch that a member of the Aleppo Military Council told her that after trying suspects the council would sentence murderers or rapists to death and execute them.

Human Rights Watch is also concerned that opposition forces seem to be holding some people for extortion or to use in prisoner exchanges. When Human Rights Watch was at the Maare detention facility, the head of the prison called detainees’ families in Human Rights Watch’s presence, informing them that the detainees had been sentenced to a fine and that they would be released if the family paid.

One detainee interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the FSA had asked him to pay three million Syrian pounds (about US$45,000) to be released, while, he said, others were asked to pay only 200,000. The detainee believed that the amount asked for his release was higher because he came from a town considered to be pro-government. The FSA fighters from Latakia said that they were keeping the 40 prisoners so that they can use them in a prisoner exchange.

Accountability for International Crimes

With respect to people within the control of a belligerent party’s forces, humanitarian law requires the humane treatment of all civilians and combatants who are captured or otherwise not capable of fighting due to injuries or other reasons. It prohibits violence to life and person, particularly murder, mutilation, cruel treatment, and torture.

Serious violations of international humanitarian law can constitute war crimes under international law. These include murder, torture; cruel or degrading treatment and passing sentences or carrying out executions without a judgment by a regularly constituted court that has ensured all the basic rights to a fair trial.

Individuals are criminally responsible for war crimes they commit or are otherwise implicated in, including through aiding and abetting, facilitating, ordering, or planning the crimes. Commanders and civilian leaders may be prosecuted for war crimes committed by their subordinates as a matter of command responsibility when they knew or should have known about the commission of war crimes or serious violations of human rights and took insufficient measures to prevent them or punish those responsible.

International human rights law, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), continues to be applicable during armed conflicts. These treaties guarantee everyone their fundamental rights, many of which correspond to the protections afforded under international humanitarian law, including the prohibition on torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, nondiscrimination, and the right to a fair trial for those charged with criminal offenses. It also includes the basic freedom from arbitrary detention.

The ban against torture and other ill-treatment is one of the most fundamental prohibitions in international human rights and humanitarian law. Common Article 3 to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, applicable during non-international armed conflicts, requires protecting anyone in custody, including captured combatants and civilians, against “violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture” and “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment.”

No exceptional circumstances can justify torture. Syria is a party to key international treaties that ban torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment under all circumstances, even during recognized states of emergency. These treaties require all states party to them – most countries in the world – to investigate and prosecute, or extradite to face prosecution, anyone within their territory against whom there is evidence of responsibility for torture. When committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population – as part of organizational policy, torture constitutes a crime against humanity under customary international law and the Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court.

Extrajudicial and summary executions are serious violations of both international human rights law and international humanitarian law. In situations of armed conflict they constitute war crimes. If they are committed as part of a policy and are widespread or systematic they constitute crimes against humanity.

Most countries are parties to treaties requiring them to arrest and prosecute, or extradite, people in their territory suspected of committing international crimes, including crimes against humanity, war crimes, torture and enforced disappearances – wherever they were committed. Crimes against humanity include unlawful killings (including extrajudicial and summary executions), torture, and arbitrary detention when conducted on a widespread or systematic scale as part of state or organizational policy.

The same treaties also require countries to arrest and prosecute, or extradite, those who ordered or assisted such crimes, as well as military or civilian commanders who knew or should have known of such crimes committed by their subordinates and failed to prevent them. Countries are prohibited from issuing amnesties or limitation dates on prosecutions for international crimes meaning that perpetrators who initially avoid prosecution can be pursued for decades to come.