(Istanbul) – Turkey’s parliament should adopt a strong, comprehensive law to curb domestic violence, Human Rights Watch said today. Parliament is debating a draft bill and is likely to vote on March 7, 2012. The draft law would replace Turkey’s existing domestic violence law and improve the systems to provide protection against domestic violence and offer enhanced support for victims.

“Thanks to the work of hundreds of women’s rights groups and the government minister in charge of this issue, Turkey has an incredible opportunity to protect millions from domestic violence,” said Gauri van Gulik, global women’s rights advocate at Human Rights Watch, “Now we need to see the political will to make these provisions a reality.”

The draft law is not finalized, but in its current form, the new “Law for the Protection of the Family and Prevention of Violence against Women” would widen the scope of protection. Turkey’s current domestic violence law only applies to married women. The new law would apply to all women, whether married or not, as well as children and other family members.

The draft law would also provide for the police and local administrative authorities and family courts to grant various levels of protection and support services to victims of violence or to those at risk of violence. The bill would require government services such as shelter and temporary financial support, in some cases even escalating to providing a new identity for the victim. The draft law also provides for family courts to impose sanctions on those responsible for the violence, including court orders to place them under surveillance.

Finally, the law states that the Ministry for the Family and Social Policies will establish “violence prevention and monitoring centers,” which would increase resources and staff dedicated to combating domestic violence and assist in carrying out the law.

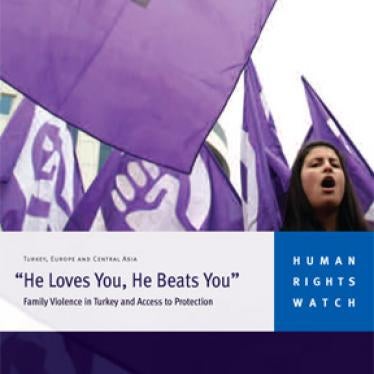

A 2011 Human Rights Watch report, “‘He Loves You, He Beats You’: Family Violence in Turkey and Access to Protection,” documents brutal and long-lasting violence in Turkey against women and girls by husbands, partners, and family members, and the survivors’ struggle to seek protection. It showed that there are significant gaps in Turkey’s existing domestic violence law and implementation failures by police, prosecutors, judges, and other officials, making the protection system unreliable. Many of the shortcomings analyzed in this report are addressed by the draft law.

Gülşah S., 22, a woman from Van who was interviewed for the report, was denied a protection order because she was in a religious marriage. She had moved into her husband’s family’s house and several family members beat, raped, and starved her, and tried to kill her infant. She told Human Rights Watch: “My father-in-law forced himself on me several times. The family did not give me food…. When I got pregnant, they tried to force an abortion on me, and then they tried to kill the baby when they saw it was a girl.”

A family court had rejected her petition for a protection order because her marriage is not considered official. Under the new law, Gülşah S. would be entitled to seek a protection order and the police would be obliged to check to make sure she was not being threatened or harmed.

The draft law refers to a groundbreaking regional treaty adopted in 2011, the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence. This treaty, also known as the “Istanbul Convention” because Turkey hosted the signing, creates a comprehensive legal framework to combat violence against women through prevention, protection, prosecution, and victim support.

Women’s rights groups and the Family and Social Policies Ministry worked on and negotiated a draft law for months, finalizing it on January 31, when it was submitted to the council of ministers. However, on February 24, the prime minister’s office produced a substantially altered version of the draft law. The new version changed the title to include “protection of the family,” reduced commitments to establishing the violence prevention and monitoring centers, and removed all references to gender equality.

The version from the prime minister’s office was sent to the equality commission of the parliament (KEFEK). But after women’s groups expressed dismay with the altered draft, the justice committee of the parliament considered both versions and reinstated many of the original provisions. It is the compromise version that is expected to be put to a vote on March 7.

Human Rights Watch understands that women's organizations in Turkey are proposing a series of last-minute additions and amendments to the law to strengthen its provisions. These include concrete steps such as introducing a one-year time-frame for the establishment of 15 violence prevention and monitoring centers.

“This could be a proud moment for Turkey if the final law includes tangible commitments to stop domestic violence and help victims when it occurs,” van Gulik said. “The government has to show it cares about women as individuals with rights, not just as members of families.”