To: Vitaliy Zakharchenko, Minister of Internal Affairs of Ukraine

Dear Mr. Zakharchenko:

We are writing to raise our concern about the arbitrary detention of some or all of a group of 125 Somali nationals detained at the Zhuravychi Migrant Accommodation Centre (MAC). Some of them are registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the Ukrainian authorities as asylum seekers. Around 80 have told UNHCR they want to apply for asylum in Ukraine, but have not been allowed to do so.

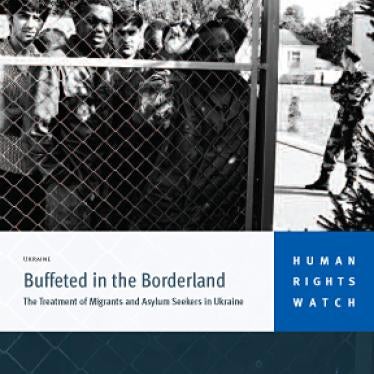

The arbitrary detention of many or all members of this group mirrors the situation of thousands of asylum seekers in Ukraine who are or have been arbitrarily detained because they have not been provided access to Ukraine’s asylum procedure, have been wrongly excluded from the procedure, or have not been allowed to pursue appeals of negative decisions on their claims. Our December 2010 report, Buffeted in the Borderland: The Treatment of Migrants and Asylum Seekers in Ukraine, documented how the applications of detained asylum seekers are frequently not processed, how inordinate numbers are rejected as manifestly unfounded, and how immigration detainees in Ukraine do not have consistent or predictable access to a judge or other authority, or access to legal representation to challenge their detention. Nor, our report found, is there individual assessment of the need to detain a migrant or asylum seeker, as required by international law.

Judging by the treatment of the group of 125 Somali nationals, it appears the abuses are ongoing.

Because at the time of our December 2010 report, Ukrainian law did not provide for complementary protection based on conditions of generalized armed violence in the country of origin, Ukrainian authorities informed us at that time that Ukraine did not grant Somalis refugee status (when the report was released in 2010, we were able to find only two known cases of Somali nationals receiving the status).

Human Rights Watch has documented widespread, ongoing human rights abuses in Somalia and we note the practical difficulty of returning rejected asylum seekers to a country that not only lacks a diplomatic mission in Ukraine but also lacks a functioning government. We refer you to UNHCR’s Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Asylum-Seekers from Somalia of May 5, 2010 (HCR/EG/SOM/10/1):

Somalis from southern and central Somalia seeking asylum and protection due to the situation of generalized violence and armed conflict in their places of origin or habitual residence and whose claims are considered as not meeting the refugee criteria under Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention or Article I(1) of the OAU Convention, should be granted international protection under the extended refugee definition in Article I(2) of the OAU Convention. In States in which the OAU Convention does not apply, a complementary/subsidiary form of protection should be granted under relevant national and regional legal frameworks. The widespread disregard of their obligations under international humanitarian law by all parties to the conflict and the reported scale of human rights violations make it clear that any person returned to southern and central Somalia would, solely on account of his/her presence in southern and central Somalia, face a real risk of serious harm.

Human Rights Watch welcomes the recent amendments to Ukraine’s law “On Refugees and Persons in need of Complementary or Temporary Protection” which introduced complementary forms of protection to protect people fleeing indiscriminate violence arising from armed conflict and other human rights abuses.

We also wish to bring to your attention the June 28, 2011 ruling of the European Court of Human Rights in Sufi and Elmi v. the United Kingdomthat returning these Somalis to Somalia constituted a violation of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which prohibits the return of anyone to a place where they would face torture or inhuman and degrading treatment. The court found:

The Court considers that the large quantity of objective information overwhelmingly indicates that the level of violence in Mogadishu is of sufficient intensity to pose a real risk of treatment reaching the Article 3 threshold to anyone in the capital. In reaching this conclusion the Court has had regard to the indiscriminate bombardments and military offensives carried out by all parties to the conflict, the unacceptable number of civilian casualties, the substantial number of persons displaced within and from the city, and the unpredictable and widespread nature of the conflict. The court further found that the UK would have returned the Somali asylum seekers to the Mogadishu International Airport and that they would not be able to travel safely to find internal flight alternatives elsewhere in the country. It therefore barred their return to Somalia as a violation of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Given the European Court of Human Rights ruling, it would appear to be unlawful to deport any Somalis to Mogadishu at the present time. While we believe that many Somalis would qualify for refugee status under the 1951 Refugee Convention, following the UNHCR Guidelines on Somali asylum seekers, we call on the Ukrainian authorities to utilize this new law to provide complementary protection to Somali nationals who do not qualify as refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Somali nationals in particular seem to be facing a vicious cycle of repeat detention during their stay in Ukraine. Ukrainian law provides that migrants and asylum seekers may only be detained for a maximum of 12 months. However, as we noted in our 2010 report, the law does not prohibit the authorities from re-arresting migrants as soon as they have been released and then detaining them again for the maximum permissible period. When released from a Migrant Accommodation Center, migrants are usually provided with certificates saying that they are on their way to the embassy and are given five days to reach it. However, since there is no Somali embassy in Ukraine, they have nowhere to go.

It is a common practice for Somali migrants to be re-arrested shortly after leaving detention, after the five days had expired, and detained again.

The European Court of Human Rights held in John v. Greecethat the immediate re- arrest and detention of a migrant without any additional elements that would justify an independent ground for renewed detention constitutes a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights’ right to liberty and security.

Asylum seekers often are not provided with documents that protect them from arrest after filing an appeal of the initial rejection of their asylum claims with the court or with the State Migration Service. During that period of time, they frequently get arrested by police for violating the rules of stay in Ukraine and are then held for the maximum period of administrative detention.

As you may be aware, 58 of the group of Somali nationals recently went on hunger strike to protest against the Ukrainian authorities having prevented them from lodging asylum claims or not having processed their claims fairly. They are also protesting against their arbitrary detention; since Ukraine cannot deport them back to Somalia, their administrative detention for the purpose of holding them pending deportation is arbitrary.

Human Rights Watch spoke with three members of the group who are being held at the Zhuravychi MAC. They told us that the majority of the group have been repeatedly arrested and detained over the past year or more. They also said that some members of the group were at different stages of appealing rejection of their asylum application by the State Migration Service and that others had been detained before they had been allowed to lodge their appeals or that no action had been taken on claims filed while in detention, leading them to believe that the authorities had not actually accepted their applications for asylum or their appeals.

A 21-year-old Somali detainee told Human Rights Watch that he wanted to appeal the Federal Migration Service’s rejection of his asylum application as manifestly unfounded or abusive, but that days later the police arrested and detained him on suspicion of being unlawfully in the Ukraine, and that he was not able to appeal the rejection of his claim. “I was rejected, arrested and sent to Chernigiv,” he said. “No court, nothing.”

After being transferred from the Chernigiv THF to the Zhuravychi MAC, the man was neither allowed to access legal representation nor given the opportunity to appear in court to challenge his detention despite the legal requirement in Ukraine that a court must order the transfer of migrants from temporary holding facilities to migrant accommodation centers. Shortly after his release in May 2011, the police arrested him again on suspicion of being unlawfully present in Ukraine and he was transferred to the Zhurvychi MAC where he remains today.

Another Somali man told Human Rights Watch he had been detained multiple times and had spent altogether almost three years in detention. He also told Human Rights Watch about abuse he had suffered at the hands of Ukrainian border guards in 2010 after Slovak border guards returned him to Ukraine. He said the Ukrainian border guards dislocated his shoulder and subjected him to electric shocks during interrogations about smuggling networks. This alleged physical abuse is consistent with the key conclusions of our 2010 report: half of the 160 migrants we interviewed reported they were physically abused, with some cases rising to the level of torture.

We urge you to take positive steps to address the serious ongoing flaws in Ukraine’s migrant detention and asylum systems.

In particular, we urge you to:

1)Immediately provide asylum seekers, including Somali asylum seekers held in the Zhuravychi MAC, with the forms and other documents needed to lodge asylum claims and appeals of negative decisions, process their claims and appeals promptly, and keep them informed about the process.

2)Utilize the new law on complementary protection by providing this protection to Somalis who do not qualify for asylum under the 1951 Refugee Convention but who cannot be returned to Somalia because of ongoing armed conflict and generalized violence in that country.

3)Release all Somali asylum seekers who are being held in administrative detention pending deportation, which cannot be carried out.

4)Ensure that all migrants being held in administrative detention have access to lawyers and courts and that their right to challenge their detention is respected. The need for detention should be subject to regular reviews before administrative and judicial authorities who have the authority to order the detainee's release.

5)Ensure access to the Zhuravychi MAC broadly for NGO monitors and lawyers in addition to those who are implementing partners of UNHCR.

6)Amend the Code of Ukraine on Administrative Offenses and the Law of Ukraine on Legal Status of Foreigners and Stateless People to limit the use of immigration detention in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights: immigration detention should only be carried out when actual removal proceedings are ongoing against that person, where detention is, as a last resort, shown to be necessary to secure that person’s lawful removal, or where the person presents a danger to the community.

7)Cooperate with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration in finding and facilitating solutions for Somali migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees in Ukraine, including resettlement.

We thank you for your attention to this matter, which we will continue to closely monitor and look forward to your response.

Sincerely,

Hugh Williamson

Executive Director

Europe and Central Asia Division

Human Rights Watch

Copy to:

Mr. Davydenko Viktor Mykhaylovych

First Deputy Director, State Department of Nationality and Registration of Individuals, Ministry of Internal Affairs

Mr. Mykola Kovalchuk, Head of the State Migration Service of Ukraine

Mr. Oleh Zarubynskyj, Head of Parliamentary Human Rights Committee,

Mrs. Nina Karpachova, Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights,

Mr. Shisholin P.A., First deputy of the Head of the State Border Guard Department