I voted on Tuesday. I climbed up the steps of the building where the voting took place, waited a short while, read the sample ballot, gave my name, signed in, and voted. Democracy in action.

But imagine if you needed someone to carry you up and down the stairs, if you couldn't see the ballot, speak, or sign your name? Would your right to vote be protected? What if you were required to pass a test to be considered "worthy" of voting?

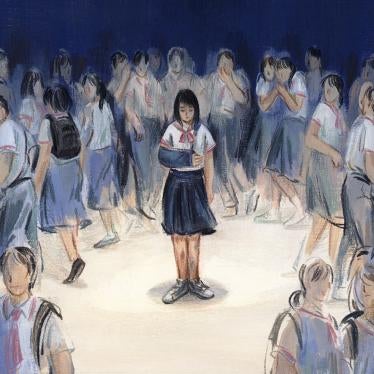

The right to vote is a fundamental part of living in a democracy. History is filled with often-bloody accounts of disenfranchised groups fighting for their right to vote. In a country that now has an African-American president and a female secretary of state, it seems incomprehensible that not so many years ago, both would have been denied the right to vote. Yet, for many members of the largest minority in the world -- people with disabilities -- disenfranchisement is still the norm.

According to a survey before the last presidential election, 39 US states disqualified voters who were judged "mentally incompetent" by a court. In Kentucky and Mississippi, for example, election laws refer to people with mental or intellectual disabilities as "idiots." Yet, what is the standard for mental competence to participate in democracy? As I looked at the ballot Tuesday, I was uncertain of the positions of some of the candidates. Is voting based solely on party affiliation rational? If I chose based on the name alone or upon a photo I'd seen of the candidate, would this qualify me as incompetent?

But disenfranchisement is not limited to the issue of "competence." To be able to vote, a potential voter needs access to information about the election and an accessible polling site. If information about the candidates, or even the date of the election, is not made available in an accessible way -- through Braille or in a simplified format, for example, then people with disabilities are excluded practically even if they are included legally.

Even when states try to accommodate them, unless they reach out to voters with disabilities so they know about resources that are available and the locations of accessible polling places, voting may not seem like an option. While federal laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Help America Vote Act of 2002 have required states to provide "reasonable modifications" and at least one accessible voting machine, these standards are inadequate and people with disabilities still face inequality at the polls.

Last summer, in American Association of People with Disabilities v. Harris, a federal court ruled that Florida's lack of disability-accessible voting equipment - which prevented voters with disabilities from being able to cast a secret vote -- was acceptable. The reason? The voting machines are temporary structures, so they are not covered by the term "facilities" in the Americans with Disabilities Act. The court also ruled that the lack of secrecy in voting was not a violation. It's hard to imagine that other voters would accept having to cast a ballot out in public with such a flimsy excuse.

Disenfranchisement primarily occurs today as a result of court-appointed guardianship programs because many states bar people under guardianship from voting. A guardian is granted the legal authority and responsibility to care for someone who is deemed by a judge to be unable to care for themselves. In 2009, in Estate of Posey v. Bergin, a man who had been placed under his daughter's guardianship as a result of disabilities and issues stemming from his alcoholism, was denied the right to vote. The Missouri appellate court, while recognizing the plaintiff's desire to vote and the fact that his guardianship was predicated on his prior alcoholism, held that under current Missouri law, his disenfranchisement was legal.

The new Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities guarantees the right to political participation to all people with disabilities, without exception. The US has signed, though not yet ratified, this important treaty. It should still comply with its principles of non-discrimination, equality, inherent dignity and individual autonomy -- including the freedom to make one's own choices.

While many states have adopted a variety of accessibility procedures and polling place requirements, since voting practices are primarily determined on the state level, there is a lack of consistency and enforcement across the states and even across counties.

State governments need to amend voting statutes and implement practical steps to ensure that people with disabilities can get to the polls and cast their ballots. These steps include providing Braille ballots and information about candidates and the political process in easy-to-understand formats. This also involves training election officers on how to interact with and support people with various types of disabilities.

Enabling people with disabilities to vote is fundamental to ending discrimination and to ensuring democracy. With another presidential election coming up, the states need to get busy.

Shantha Rau Barriga is the Disability Rights Researcher and Advocate for Human Rights Watch, which is a member of Save the Vote, a global campaign on the right to political participation for people with disabilities.