On Saturday, Oct. 29, thousands of people in Washington will walk to raise attention and money for HIV/AIDS. AIDS walks in cities throughout the world are an occasion to remember those who have died and to renew our hopes for an end to the epidemic.

There was an AIDS walk in southern Vietnam last year too, in Lam Dong province, and in some ways it looked like any other. People walked behind a banner reading “No prejudice and discrimination against HIV/AIDS patients.” There were speeches, films and performances, many around the theme of “universal access and the right to health care.”

But looking closer, it became clear that this wasn’t a walk in solidarity, or remembrance, or hope. It was a forced march.

Hundreds of marchers stood in rows, in identical clothes. There were no smiles or frivolity. No demands were chanted for the government to do more. No joyful or tearful reunions. The march did not pass through the gay district nor did it wind its way downtown to the halls of government and power.

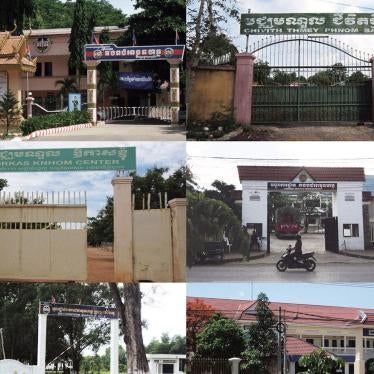

The march was at the “School for Education, Vocational Training and Job Placement No. 2.” Despite its benign-sounding name, the “school” is really a detention center for drug users. Detainees face years of forced labor and physical abuse, including torture.

The HIV epidemic in Vietnam is concentrated among injection drug users, who desperately need community-based, effective services for drug dependency treatment and HIV prevention and care. But something is seriously rotten when “education” centers operating as forced labor camps organize AIDS marches under slogans calling for an end to prejudice against people living with HIV.

It is equally perverse that some of the world’s most significant bilateral and multilateral donors fund services inside these centers, seeming to turn a blind eye to the abuses there.

Vietnam’s forced labor centers are a remnant of a hard-line communist approach. Drug users were one of many social groups rounded up and subjected to “re-education through labor” following the victory of North Vietnam in 1975.

But as Vietnam’s economy has modernized, the system has expanded. In 2000, there were 56 drug detention centers across Vietnam; by early 2011, that number had risen to 123. The length of time in detention has steadily grown.

Human Rights Watch interviewed people who had been held in various centers under the control of Ho Chi Minh City authorities. Many were afraid they could be sent back to detention, where they would face more forced labor and abuse. Three had been held in “School No. 2.” They told us they husked cashews, made shopping bags and sewed clothes, all in the name of “labor therapy.” Detainees who refused to work were beaten or put in punishment cells.

Even when they received some payment, those wages were garnished for food, lodging and “management fees.” People told us of leaving “rehabilitation” centers owing money that they, or their families, had to pay.

Rates of HIV inside the centers are hard to state with any certainty: estimates have ranged from 15 to 60 percent. Most centers offer no medical care, so donors such as the [US] President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the World Bank have supported programs for detainees.

It’s easy to understand why the donors are there. The government centers hold thousands of drug users, and it’s harder to reach drug users outside of detention when they live in fear of being arrested. Donor agencies told us that they couldn’t turn their back on people in these centers, who might die without their support.

Yet donors are turning their backs when it comes to documenting abuses in the centers, and demanding that the Vietnamese government shut them down. Without doubt, HIV treatment can be life-saving. However, under Vietnamese law, HIV-positive people in detention have a right to be released if drug detention centers can’t provide appropriate medical care. Donor support for expanded HIV treatment inside centers can have the perverse impact of enabling the government to continue detaining people living with HIV, maximizing profits while still denying detainees effective drug dependency treatment.

In 2009, more than $100 million was provided by international funders for AIDS programs in Vietnam. That sort of money should buy a lot more accountability than has been seen. The centers have been shown repeatedly to be ineffective at treating drug dependence and should be immediately shut down. Until they are, donors should demand that Vietnam stop detaining new drug users and release all those currently living with HIV. Donors should support community-based drug treatment, which is less expensive, more effective and more respectful of human rights.

“No prejudice against HIV/AIDS patients.” That’s a banner worth walking behind. To make it real in Vietnam will require those walking in Washington to ask tough questions of U.S. global AIDS policies. Act locally, think globally. Those who are out on Saturday should raise money for local efforts to fight AIDS, but walk in solidarity with those who are locked up, tortured and forced to march in Vietnam.