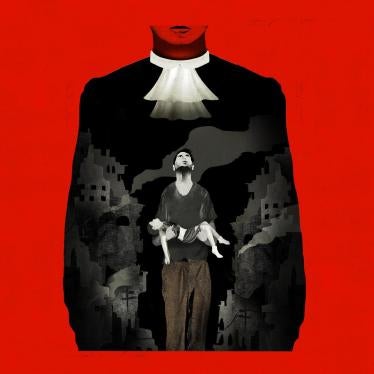

Justice has finally caught up with Ratko Mladic. The Bosnian Serb warlord, an alleged mastermind of some of the worst crimes committed during the 1992-1995 Bosnian war, including the Srebrenica genocide, is sitting in the United Nations detention unit in The Hague after nearly 16 years on the run.

His arrest and surrender to the Yugoslav tribunal brings the victims of the war one step closer to the truth. It also marks a high point for international criminal justice, sending the message to war criminals and would-be war criminals alike that no one is beyond the reach of the law when it comes to humanity's worst crimes.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has come a long way since its creation nearly two decades ago. Only one of the 161 people it indicted remains at large, no small achievement considering the court lacks its own police force and must rely on the cooperation of states to apprehend its suspects. The European Union and especially the Netherlands played a crucial role in pressuring Serbia to arrest Mladic, using the carrot of membership in the bloc in much the same way it helped persuade the Croatian authorities to surrender General Ante Gotovina to the tribunal in 2005.

However, make no mistake: the road ahead will not be easy. As one of the war's most senior figures, Mladic faces 11 charges for the most serious crimes involving a range of crime scenes. In each case the prosecutors must establish beyond reasonable doubt Mladic's personal responsibility and how his orders led to the atrocities his troops committed. If contentions by his family and lawyers that he is seriously ill have any truth to them, the judges will have to tread carefully in balancing the demand for justice against their responsibility to assess his fitness to stand trial.

The ICTY has already shown its considerable experience-and success-in trying complex factual allegations against high-profile defendants. The tribunal has sentenced 64 defendants for war crimes, including top generals from Bosnia, Serbia and Croatia, and acquitted 13 defendants. Together with its sister tribunal created for the Rwandan genocide, the court has made important contributions to international humanitarian law and has generated cutting-edge legal precedents. The tribunal also helped initiate and bolster national efforts to bring other war criminals to justice in fair trials, most notably in Bosnia.

That is not to suggest the tribunal is perfect, or that its proceedings have been flawless. The ICTY is a hybrid of common and civil law traditions, and the numerous changes to its rules of procedure and evidence over the years suggest an institution grappling with how to manage complicated trials better and more efficiently. The death of the former Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic before his case reached a verdict was a bitter disappointment. His nearly four-year trial was simply too long because of the prosecution's bloated indictment, his poor health, and the considerable leeway the judges gave him as they managed his right to represent himself.

But examining the tribunal's practice in recent years indicates that it has learned important lessons. The prosecution's recently submitted streamlined indictment against Mladic, which closely matches the indictment against his co-accused, Radovan Karadzic (the Bosnian Serbs' wartime political leader), demonstrates a more pragmatic approach to seeking justice for victims. By now, the judges are much more adept at managing grandstanding self-represented defendants, including Karadzic, who is currently on trial. Mladic's trial gives the tribunal yet another opportunity to apply these lessons.

However, one challenge will remain: the need to bridge the gap between proceedings in The Hague and those who lived through the horrors of the war hundreds of miles away. The tribunal learned the hard way that ignoring this key constituency, as it did in its early years, can seriously undercut its credibility in the Balkans. The court's commitment to outreach has greatly improved over the years, and it has persevered using much-needed donor funds, including from the European Union.

With two of the most notorious accused now in the dock, more outreach and more donor funds will be needed for victims to see justice done. Indeed, the victims deserve nothing less.

Param-Preet Singh is senior counsel for the international justice program at Human Rights Watch.