(Baku) - The Azerbaijani government is using criminal laws and violent attacks to silence dissenting journalists, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Dozens of journalists have been prosecuted on criminal and civil defamation and other criminal charges. Police have carried out physical attacks on journalists, deliberately interfering with their efforts to investigate issues of public interest.

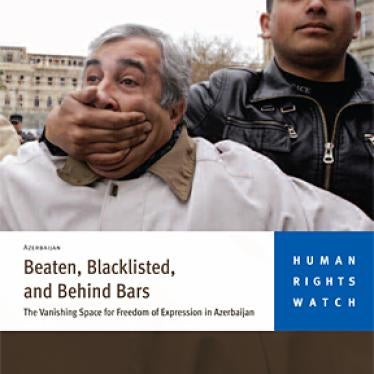

The 94-page report, "Beaten, Blacklisted, and Behind Bars: The Vanishing Space for Freedom of Expression in Azerbaijan," documents the government's efforts to limit freedom of expression. The government should free imprisoned journalists and repeal criminal libel laws that allow public officials and others to bring criminal charges against journalists and activists, Human Rights Watch said. It also should prosecute violence or threats against reporters, which now go unpunished. The attacks on free speech threaten to undermine the legitimacy of parliamentary elections scheduled for November 7, 2010, Human Rights Watch said.

"A vibrant public debate is crucial to free and fair elections," said Giorgi Gogia, South Caucasus researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. "But you can't have a free and fair vote when the people who report the news are in jail or have been harassed into silence."

At least nine journalists have fled Azerbaijan in the last three years seeking political asylum abroad.

Human Rights Watch has documented restrictions on freedom of expression in Azerbaijan for many years. For this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed over 37 print and radio journalists and editors in June 2010.

Azerbaijan abolished official state censorship in 1998. However, the government has used other, less obvious means to restrict freedom of expression and the media. In addition to prosecutions and police violence, legislative amendments in 2009 restricted journalists' ability to use video, photo or sound recording without explicit consent of the individual being recorded or filmed, even at public events. The government also banned all foreign radio broadcasting on FM frequencies. Unnecessary restrictions should be removed, and the foreign broadcasts should be allowed to resume, Human Rights Watch said.

In the past several years, state officials have brought dozens of defamation charges against journalists, and in some cases, against human rights defenders who criticize the government or who otherwise work to secure accountability for human rights violations in Azerbaijan.

Criminal defamation laws pose an inappropriate risk of chilling free speech and should be abolished, Human Rights Watch said. Criminal penalties for defamation are an unnecessary and disproportionate response to allegations that damage has been done to an individual's reputation, particularly where the issue is of significant public interest or involves public figures. Politicians and other public figures are expected to tolerate wider and more intense scrutiny of their conduct than private individuals.

"Legal cases, and especially criminal cases, against those who report or broadcast on issues of public interest is a cynical attempt by the government to impose censorship," Gogia said. "The government should be encouraging people to speak out freely, not punishing them."

The apparently politically motivated case against Eynulla Fatullayev, an outspoken critic and founder and editor-in-chief of two of Azerbaijan's largest and most popular independent newspapers, is among the most egregious, Human Rights Watch said.

Fatullayev has been in prison since April 2007 after being convicted of civil and criminal defamation for articles he had written. Six months later, he was found guilty of threatening terrorism and inciting ethnic hatred, giving him a total sentence of eight and a half years. He appealed to the European Court of Human Rights, which is April 2010 found that Azerbaijan had "grossly" and "disproportionately" restricted freedom of expression by imprisoning him. The court has ordered the government to release Fatullayev.

Two other imprisoned critics are Emin Milli and Adnan Hajizade, who were victims of an attack in a restaurant in July 2009 that was apparently staged. They were subsequently convicted of hooliganism as a result of the episode. Milli and Hajizade were well-known for criticizing Azerbaijani government policies in blog postings and were arrested a week after distributing a satirical YouTube video criticizing the government.

"Cases like Fatullayev's and the bloggers' have had a profound chilling effect on journalists and editors," Gogia said. "Fearing a similar fate, journalists often choose not to write on certain topics and limit investigative reporting, particularly on issues the government considers taboo."

Journalists, human rights defenders and others who publicly criticize the government also risk violence, threats and harassment. Journalists have been attacked by police as they carried out their professional duties, including documenting police efforts to break up peaceful protests. The authorities have failed to conduct through and impartial investigations into attacks on journalists.

A set of legislative amendments and executive decisions have further restricted freedom of expression in Azerbaijan. These include the 2009 constitutional amendments restricting journalists' use of recording devices and the ban, also in 2009, on foreign radio broadcasting on FM frequencies, which pulled the BBC, Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty off the air.

The authorities have also condoned the publication of a "black list of racketeering newspapers" by the Press Council, ostensibly a membership-based, self-regulatory body for print media. The list was represented as a way to reprimand newspapers that have breached ethical journalism standards, but in practice, it has made it harder for newspapers to get information and in some cases has led to the closing of media outlets.

Under international law the Azerbaijani government has specific legal obligations to protect the right to freedom of expression. International human rights law recognizes freedom of expression as a fundamental human right, essential both to the effective functioning of a democratic society and to individual dignity.

"The government seems to think it will protect itself by silencing and intimidating journalists," Gogia said. "Instead, it attracts international attention as a leading jailer of dissidents and critics in the region."