Eleven years ago, during NATO's air campaign against Yugoslavia, Serbian forces killed more than 40 ethnic Albanian men in a Kosovo village called Cuska (Qyshk in Albanian). This month the hand of justice finally reached the men accused of the crime.

They served in a state-sponsored militia called the Jackals, which descended upon Cuska in the early morning of May 14, 1999. The militia members separated the menfolk from the women and children. After looting, they herded groups of men into three homes. Gunmen opened fire with automatic weapons and set fire to the houses. One man in each house managed to survive.

I interviewed the survivors and other witnesses two months later during an investigation of the killings for Human Rights Watch. The witnesses described how the Serbian forces arrived, shot people in various corners of the village, and then led the captured men to their deaths. I saw the charred remains of the three homes, one with bone fragments amid the ash and cinder.

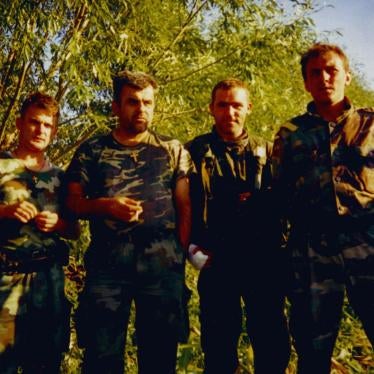

Looking at photos of local Serbian militia members I had collected, the witnesses identified two men who, they said, had participated in the killings, and a third who was present in the nearby village of Zahac on the same day, when 19 other men were killed. "Yes, he was here," one witness said, pointing at the laptop screen. The witnesses did not always know the names of the people they were identifying, but they said they would never forget the faces.

Now, the men identified by these witnesses, plus six others, will face trial. On September 11, Serbia's war crimes prosecutor announced indictments against the group for murders and other crimes in Cuska that showed "extreme cruelty, brutality, insensitiveness and ruthlessness." Another 17 men are under investigation for the killings of up to 200 ethnic Albanians in Kosovo.

The indictments show that, even after years of delay and patience, justice can reach the perpetrators of war crimes and challenge the impunity that often pervades armed conflicts.

The key now is to see that the Cuska operation's commanders also face justice. The United Nations war crimes tribunal in The Hague has tried Slobodan Milosevic and other Serbian leaders. But most of the middle managers of ethnic cleansing operations, the field commanders, still live free. The Cuska victims welcome the sight of the shooters in court, but real justice will come only when those who armed the killers and gave them their orders are held to account.

Serbia is taking active steps to join the European Union, including a more cooperative approach to resolve the ongoing dispute over Kosovo. But the European Union should insist that Belgrade arrests the commanders who committed war crimes in Cuska and many other villages in Kosovo, Croatia, and Bosnia during the war in the former Yugoslavia. First among them is the last major figure wanted by the UN tribunal, General Ratko Mladic, for the killing of about 7,500 men in Srebenica.

The Cuska arrests are one step in the process. But the EU should hold firm until Mladic is behind bars.