(Dakar) - The arrest and conviction of seven Quranic teachers who forced boys trusted to their care to beg is a significant move forward for children's rights in Senegal, Human Rights Watch said today. The men were sentenced on September 8, 2010, marking the first application of a 2005 law outlawing the practice; two more men are scheduled to face the same charges on September 9. The authorities should make the children's welfare the top priority as they work to return the boys to their families, Human Rights Watch said.

The prosecution was part of an effort by Senegalese authorities to combat the widespread practice of exploitation and forced labor endured by tens of thousands of boys entrusted to men like the accused for the purposes of learning the Quran. Each of the seven men was sentenced in a Dakar court to six months imprisonment with a suspended sentence and a fine of 100,000 francs CFA (US$200).

"The arrest and conviction of these men represents a welcome step toward ending the exploitation of vulnerable children under the guise of supposed religious education," said Corinne Dufka, senior West Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. "The Senegalese government should continue prosecuting abusers while at the same time ensuring that the boys are safely returned to their families."

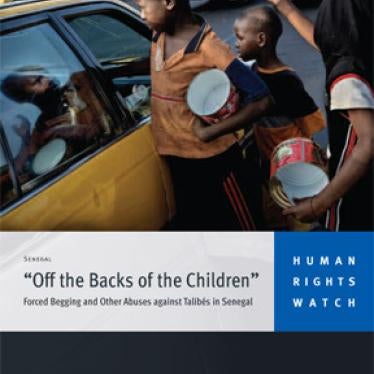

Human Rights Watch documented in an April 2010 report the system of exploitation and abuse in which at least 50,000 boys known as talibés - the vast majority under age 12 and many as young as four - are forced to beg on Senegal's streets for long hours, seven days a week, by often brutally abusive Quranic teachers, known as marabouts. Human Rights Watch documented widespread physical abuse, including severe beatings and several cases in which children had been chained, bound, and forced into stress positions for failing to hand over a required daily amount from their begging or for trying to run away. Moreover, Human Rights Watch found that the practice was clearly on the rise, doubling in some urban areas over the last decade.

Many marabouts, who serve as de facto guardians for talibés in their schools, known as daaras, conscientiously carry out the important tradition of providing young boys with a religious and moral education. But in many other residential daaras, especially in urban areas, marabouts use education as a cover for economic exploitation of the children in their charge. The children often spend four times as many hours begging as they do on Quranic studies, and Islamic scholars in Senegal have described boys leaving these daaras after five or more years of exploitation without having memorized the Quran.

The often substantial sums of money, rice, and sugar collectively brought in by begging talibés are generally not used to feed, clothe, shelter, or otherwise provide for the children in these schools. The boys often sleep up to 30 to a small room in abandoned or makeshift structures that offer little protection from rain, heat, or cold, allowing disease to run rampant. Many of the children suffer severe malnutrition, while the long hours on the street put them at risk of harm from vehicle accidents and physical and sexual abuse. In these daaras, the conditions endured by the boys amounts to a modern form of slavery, Human Rights Watch said.

The Senegalese government initially tried to address the problem by making families and marabouts aware of the dangers of forced begging as well as by supporting "modern" daaras in which boys do not beg and receive a more holistic education. However, as the number of boys subjected to the abusive practice has grown, diplomats and donors have increased pressure on the Senegalese government to tackle the problem at its root.

On August 24, 2010, Prime Minister Souleymane Ndéné Ndiaye issued an edict instructing authorities to round up all classes of beggars, including the talibés, noting that the government was "under threat from its [donor] partners." Unfortunately, the government does not appear to have made sufficient plans to house and repatriate the large number of children being taken from the abusive daaras, Human Rights Watch said. State authorities have simply released some of the boys, leaving them vulnerable to return to abusive teachers or take up life on the street.

"The crackdown should be making life difficult for those abusing the children, not the victims themselves," Dufka said.

The recent arrests and prosecutions of abusive marabouts is an encouraging sign of proactive policing and judicial efforts to combat this problem, Human Rights Watch said. Senegalese authorities involved in the investigation of the seven men told Human Rights Watch that the more than 20 child beggars they interviewed had been forced to beg for long hours on Dakar's streets to return a daily quota of between 200 and 1,000 francs CFA ($0.40-$2) each to their teachers. That information led to the arrests and convictions of the seven men.

Some of the boys have been placed in Centre Ginddi - a state-run shelter that provides food, health care, and psychosocial support while authorities work to reunite the boys with their families. However, judicial and police officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch could not specify the location of the more than 100 other boys who lived in these seven daaras, while another government representative said that most remained at their daaras under the supervision of a second-in-command.

Both of those responses raise concerns about the boys' welfare, Human Rights Watch said. While the government has primary responsibility for the children's protection, authorities should work closely with Islamic leaders, civil society, and donors to make sure that the boys are adequately housed and cared for until they can be returned to their families, Human Rights Watch said.

While there has been a noticeable decline in forced begging in Dakar since the crackdown and subsequent arrests, serious concerns remain about the protection of thousands of boys who are still on the streets or in abusive daaras. Many marabouts interviewed by news reporters have said they intend to continue forcing boys in their care to beg. Several humanitarian workers expressed concern to Human Rights Watch that as a result of the crackdown, more children were being forced to beg at night - when fewer police officers are on patrol - increasing the children's vulnerability.

Without proactive policing and sustained engagement by the government, forced child begging is likely to revert quickly to its pre-crackdown ubiquity, Human Rights Watch said. In addition to prosecuting abusive marabouts, Human Rights Watch said, the government should finalize its efforts to regulate these schools, ensuring that they conform to minimum standards that guarantee children's rights to education, health, and physical and mental development. The government should also expand the capacity and mandate of state daara inspectors to improve monitoring and to sanction or close daaras that do not meet standards for the best interests of the child.

"The Senegalese government should make use of what could be an impressive tool kit: prosecutions against traffickers and abusive teachers, regulation of all schools, and protection and supervised repatriation of victims of forced begging," Dufka said. "Senegal should not further compromise children's safety with uncoordinated and potentially harmful round-ups of street beggars."