(Nairobi) - Hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees in Kenya face abuse by corrupt and violent police and a rapidly growing humanitarian emergency in the world's largest refugee settlement, Human Rights Watch said in a new report released today. Kenya should immediately rein in abusive police and grant new land for additional camps, while the United Nations and international donors should urgently respond to Somali refugees' basic needs.

The 58-page report, "From Horror to Hopelessness: Kenya's Forgotten Somali Refugee Crisis," documents the extortion, detention, violence, and deportation at the hands of the Kenyan police faced by a record number of Somalis entering Kenya. The new refugees are joining over a quarter of a million fellow refugees struggling to survive in camps designed for one-third that number.

"People escaping violence in Somalia need protection and help, but instead face more danger, abuse, and deprivation," said Gerry Simpson, refugee researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. "Somali asylum seekers should be able to cross the border safely and get the aid in Kenya they urgently need."

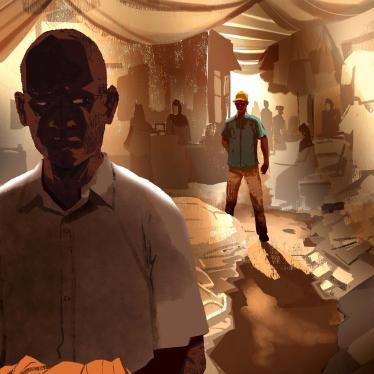

In 2008, a record yearly total of almost 60,000 Somalis sought refuge in three camps near the town of Dadaab in northeastern Kenya, while possibly tens of thousands more traveled to Nairobi. New arrivals face police extortion, violence, and unlawful deportation when trying to cross Kenya's officially closed border and end up in appalling crowded conditions in under-serviced refugee camps.

Citing security concerns, Kenya officially closed its 682-kilometer border with Somalia in January 2007, when Ethiopian troops intervened in support of Somalia's weak transitional government and ousted a coalition of Islamic courts from Mogadishu, Somalia's capital. During the past two years, an escalating armed conflict by Ethiopian and Somali government forces against an insurgency, resulting in numerous war crimes and human rights abuses, has forced almost 1 million residents of Mogadishu to flee, and provoked a growing influx of Somali refugees into Kenya. Despite Ethiopia's withdrawal in late 2008, violence continues between Islamist groups and the government, and more refugees are expected throughout 2009.

The border closure has encouraged members of Kenya's police - long known for their abusive practices against Somalis - to increase the extent of their extortion of Somali asylum seekers trying to reach the camps. The border closure has forced tens of thousands of Somalis to use smuggling networks to cross into Kenya secretly. The closure also forced the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to close its refugee transit center, where all new refugees previously had been quickly registered and given health checks before being transported to the camps.

"From Horror to Hopelessness" concludes that closing the border to refugees violates the international refugee law prohibition against forced return (refoulement) and has resulted in other serious abuses. The report quotes refugees who describe being forced back to Somalia because they could not pay bribes to Kenyan police and others who were arrested, held in appalling detention conditions in the camps or nearby towns, beaten, and in some cases deported back to Somalia.

"Kenya has legitimate security concerns and a right to control its borders, but its borders can't be closed to refugees fleeing fighting and persecution," said Simpson. "The border closure has only made Somali refugees more vulnerable to abuse and lessened the government's and UNHCR's control over who enters Kenya and who is registered in the camps."

Even if they manage to enter Kenya, the new arrivals face huge challenges. Most head to one of Dadaab's three camps, the only places in Kenya where they are entitled to shelter and other forms of care. But even in the camps, they struggle to find aid.

Since August 2008, when the local Kenyan community near the camps halted years of informal expansion and the camps were declared full, new arrivals have received no land or shelter materials and have been forced to live with relatives or strangers in cramped tents or huts. The UN refugee agency and nongovernmental organizations estimated that, by the end February 2009, more than 40,000 new shelters were needed to meet international aid standards.

The refugee agency's negotiations for more land in the area have made limited progress because impoverished local Kenyans demand that they receive more benefit from the aid agencies' presence in the area and that any new camps be managed in an environmentally sustainable way. In February, the government granted land for a fourth camp, to begin the process of decongesting the existing camps. If the local community and the refugee agency agree on detailed arrangements, 50,000 refugees are to be transferred there by mid-2009. But this will still leave an estimated 230,000 refugees in the old camps. New land for two more camps - for a total of 100,000 refugees - is urgently needed.

"There could easily be 300,000 Somali refugees in Dadaab by the end of 2009," said Simpson. "The UN's development and environmental agencies should step in immediately to help UNHCR reach an agreement with the local Kenyan communities and the government for more land."

In December 2008, the refugee agency issued an appeal for US$92 million that aims to address years of neglect in Dadaab, assist the ever-increasing rate of new arrivals, and build new camps for 120,000 refugees. In its report, Human Rights Watch called on donors to fund agencies responding to refugees' most basic needs.

Dadaab's camps - holding well over 100,000 refugees since 1992 - were severely under-funded even before the new wave of refugees started arriving in 2006 and increasingly in 2008. By mid-2008, acute malnutrition in the camps stood at 13 percent. Although registered refugees receive the minimum amount of food under international aid standards, the refugee agency acknowledges that many are forced to sell their food to buy essential non-food items such as shelter materials, firewood, and basic household goods.

Dadaab's camps are in the midst of an appalling sanitation crisis; the camps faced a cholera outbreak in February and have had others in previous years. The refugee agency estimates that more than 36,000 latrines and washing facilities are needed to reach minimum standards. A recent Oxfam report found that thousands of refugees have no access at all to the camps' poorly maintained latrines and that most women and children - half the camps' population - are rarely able to use them because they are not segregated by sex and because of overcrowding.

At best, Dadaab's crumbling two-decade-old water system provides 16 liters per person per day, four liters below minimum international aid standards, and many refugees have access to far less water than that, according to Oxfam. Under-staffed clinics facing drug shortages struggle to deal with growing chronic health needs.

"From Horror to Hopelessness" also documents the obstacles used to limit the number of Somali asylum seekers and refugees who reach Nairobi. Refugees are not entitled to humanitarian assistance if they live outside the camps. In violation of the refugees' rights to free movement in Kenya, the Kenyan authorities require them to apply for special permission to travel outside the camps. And, in contrast to rapid registration in the camps, Somali asylum seekers have until recently spent nine months or more waiting to be recognized as refugees by the UNHCR in Nairobi. While they wait, they risk extortion and abuse by Kenyan police.