(Lagos, October 11, 2007) – Politicians have hijacked democratic institutions in Nigeria by turning elected offices into vehicles for political violence and corruption, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Human Rights Watch called on President Yar’Adua and the Nigerian parliament to end the impunity enjoyed by abusive politicians and to enact reforms to make government more transparent and accountable.

The 123-page report, “Criminal Politics: Violence, ‘Godfathers’ and Corruption in Nigeria,” documents the most important human rights dimensions of this crisis of governance: politicians and other political elites openly encouraging systemic violence; the corruption that fuels and rewards Nigeria’s violent brand of politics at the expense of the general populace; and the impunity enjoyed by those responsible for these abuses that denies justice to its victims and is a roadblock to reform.

“In place of democratic competition, struggles for political office are waged violently in the streets by thugs recruited by politicians,” said Peter Takirambudde, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Once in office, these politicians use their power to undermine basic human rights and enrich themselves at the expense of Nigeria’s impoverished populace.”

The report also describes the human cost of this dysfunctional governance, including lives lost to political violence, voters denied a voice in the electoral process, and youth recruited into violent gangs by politicians. The report is based on scores of interviews with government and police officials, civil society activists and victims of human rights abuse, along with gang members, politicians and political “godfathers” implicated in serious human rights abuses.

Human Rights Watch called upon Nigeria’s federal government to demonstrate its commitment to reverse these trends by enacting key reforms to make government institutions more accountable and transparent. Key early steps should include a robust and transparent government response to the recommendations of its recently constituted electoral reform panel; passage of Nigeria’s long-delayed Freedom of Information Law; and to extend a far greater degree of budgetary transparency to state and local levels. Just as important, the Yar’Adua administration should make a serious effort to investigate and hold accountable politicians and government officials, including leading members of the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP), implicated in serious human rights abuses.

“President Yar’Adua and the Nigerian parliament can and must play a pivotal role in reversing Nigeria’s abusive patterns of governance,” said Takirambudde. “Strong signs of renewed commitment to accountability and reform could begin to move Nigeria down the road to better governance and real respect for human rights.”

Nigeria returned to civilian rule in 1999, a turning point in a post-independence history that had been dominated by a series of corrupt and authoritarian military governments. But the end of military rule has brought only a hollow semblance of democratic governance, with nationwide elections in 1999, 2003 and 2007 undermined by widespread fraud and violence. Far from evincing progress, each of those elections has been bloodier and more pervasively rigged than the last. The April 2007 elections that saw the current government to power were riddled by fraud and violence, and were universally condemned by domestic and international observers.

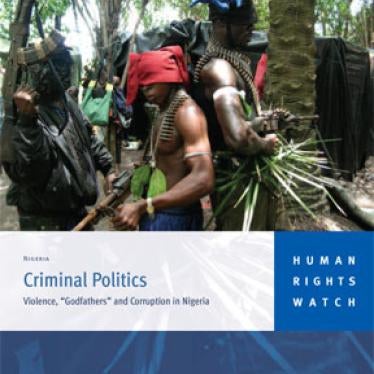

The report documents how many politicians openly mobilize gangs of thugs to terrorize members of the public, including political opponents, and to forcibly rig elections. In Anambra State, the powerful 2007 PDP gubernatorial candidate Andy Uba hired armed “cult” gangs to seize control of the electoral process – an effort that led to bloody fighting in the streets of the state capital as gangs fought among themselves over the spoils. One gang member interviewed by Human Rights Watch compared Uba’s campaign organization to an “oil well” that could only be tapped into by carrying out acts of violence.

In Rivers State, at the heart of Nigeria’s restive Niger Delta, the efforts of local politicians to arm and hire criminal gangs to rig elections have spiraled out of all control. Bloody fighting in 2004 between rival gangs armed by the administration of then-Governor Peter Odili during the 2003 election cycle claimed dozens of lives, but those responsible were not held to account. The same pattern has now repeated itself in 2007, with inter-gang fighting in the streets of Port Harcourt in July claiming dozens of civilian lives and prompting a full-scale military intervention. Still, none of the individuals most responsible for that violence have been brought to account.

In Gombe State, gangs collectively known as Yan Kalare grew into a terrifying force since being sponsored in 2003 by local politicians, and then largely escaped the control of their benefactors. The gangs assaulted, raped and murdered, and none of their sponsors have been held accountable. One member of Gombe’s elder forum lamented to Human Rights Watch that, “We are ruled by gangsters. The major source of criminal activity in Gombe is the politicians and their militias.”

In some parts of Nigeria, the need to mobilize vast sums of money and large numbers of political thugs to compete in politics has given rise to mafia-like power brokers known as “godfathers,” who do not seek to occupy the elective offices they control, but instead use violence and corruption to rig their proteges into positions of influence. In return, they demand regular cash payments embezzled from government coffers as well as the right to control the distribution of government resources, jobs and contracts as patronage. In some cases these relationships are spelled out in remarkably explicit terms – as in the case of a written contract and loyalty oath signed by PDP godfather Chris Uba and then PDP gubernatorial candidate Chris Ngige in 2003.

In Oyo State, PDP godfather Lamidi Adedibu sent gangs into the streets in retaliation for independent action by his one-time protege and then-Governor Rashidi Ladoja. Ladoja’s supporters retaliated in kind. The resulting violence claimed dozens of lives and spread even to the floor of the State House of Assembly. Adedibu also mobilized thugs and attempted to subvert the voter registration process to help rig current PDP Governor Christopher Alao-Akala into office in 2007. Governor Akala told Human Rights Watch that “Chief Adedibu has sponsored everybody. Everybody who is who and who in Oyo State politics has passed through that place [Adedibu’s compound in Ibadan].”

Law enforcement agencies have usually turned a blind eye to crimes linked to influential politicians or powerful godfathers, even where ample evidence of criminal wrongdoing exists. Since the end of military rule, attorney generals at both the state and federal levels have not brought charges against a single prominent politician for involvement in arming or fomenting political violence. In many cases, police personnel have been implicated in the kinds of abuse they should be working to prevent. As one state’s commissioner of police acknowledged to Human Rights Watch, “There are even policemen and soldiers who can be used by people in power to do what thugs would normally do.”

The report notes with concern that no real effort has been made to hold politicians to account for their open mobilization of violence and corruption to secure political power. Until 2007, limited efforts at investigating and prosecuting corrupt politicians focused on enemies of the Obasanjo administration, undermining if not destroying the credibility of those efforts altogether. The government’s much-vaunted Economic and Financial Crimes Commission lost much of its credibility through selective targeting of government opponents in the run-up to the election, and has since done nothing to demonstrate that it possesses the requisite independence to do its crucial job effectively.

The administration of President Yar’Adua is a product of Nigeria’s fraudulent 2007 elections. Nonetheless, his government has embarked on the beginnings of a process of electoral reform that holds out some hope of progress. And thus far it has respected the independence of Nigeria’s increasingly assertive judiciary. However, the federal government has done nothing to end the impunity enjoyed by the perpetuators of Nigeria’s worst abuses. Along with its broader importance that failure will undermine any effort at electoral reform – no amount of institutional tinkering can safeguard the next election if abusive politicians are able to pour their effort into subverting that process and the rule of law more generally with impunity.

“The failure of Nigeria’s 2007 elections is not a problem that can be dealt with in isolation,” Takirambudde said. “Those polls were a stark reflection of much deeper problems that Nigeria’s federal government has thus far allowed to grow unchecked.”