Guerrillas’ use of antipersonnel landmines is having a devastating impact on civilians in Colombia, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. New reported casualties have escalated dramatically in recent years, due largely to increased use of landmines by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas.

Antipersonnel landmines are easy to manufacture from cheap, readily available materials. The FARC has invoked the low cost of building them as a justification for their use, calling the landmines the “weapon of the poor.” While the majority of landmine casualties are military, the mines are also injuring hundreds of Colombia’s poorest, most vulnerable citizens every year.

“By using antipersonnel landmines, the FARC are leaving Colombian civilians who have no part in the conflict maimed, blind, deaf or dead,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director for Human Rights Watch. “There is simply no excuse for using these indiscriminate weapons.”

The 34–page report, “Maiming the People: Guerrilla Use of Antipersonnel Landmines and Other Indiscriminate Weapons in Colombia,” is accompanied by an extensive photo and audio slideshow in English and Spanish, and documents the impact on civilian survivors of guerrillas’ use of antipersonnel landmines in Colombia, as well as the difficulties that such survivors face in obtaining needed assistance from the government.

When they suffer a landmine injury, survivors’ whole lives are seriously affected. The incident not only causes physical effects, but also often impacts their mental health, their ability to support themselves and their families, and their ability to remain in their homes.

“I live dying,” said one farmer in his fifties who lost a leg and most of his eyesight when he stepped on a landmine in the state of Santander. “Now I live from handouts and from the food my children give me. … I’ve been sick for three years and, still, I don’t die.”

Human Rights Watch’s report also describes the FARC’s use of other weapons, such as gas cylinder bombs, in civilian areas. The bombs are impossible to aim accurately, and regularly hit civilian targets such as houses and churches, injuring or killing civilians.

The laws of war forbid the use of weapons, such as antipersonnel landmines, which have an indiscriminate impact. In addition, individuals and commanders of armed groups who intentionally direct attacks against civilians could be prosecuted for war crimes, or — if the attacks are part of a broader systematic attack against a civilian population — even crimes against humanity, under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

“If there is evidence that FARC commanders are intentionally directing attacks against civilian populations with these landmines or similar weapons, they could face prosecution by the ICC,” said Vivanco.

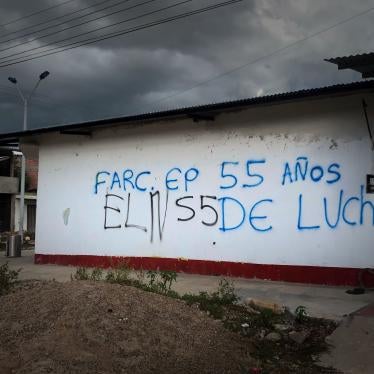

The report recounts a Human Rights Watch interview with Francisco Galán, a spokesman for the National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrillas, which also use antipersonnel mines. Galán, then in detention, stated that his group did not believe that the laws of war apply to them, and that instead a “creole” version of such laws should apply in Colombia.

The ELN has offered the Colombian government a temporary ceasefire in the context of peace negotiations. Presumably, the ceasefire would include a cessation in the use of antipersonnel landmines.

“The cessation of mine production and use should be unconditional and permanent,” said Vivanco. “The ELN should not be treating the rights of Colombia’s civilian population as a bargaining chip.”

While the guerrillas are the main users of antipersonnel landmines in Colombia, paramilitary groups have also been known to stockpile the weapons.

The Colombian government has banned the use of antipersonnel landmines under the terms of the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, and its laws provide for medical, economic, and other benefits for landmine survivors. Colombia is also receiving substantial international aid, including from the European Union, for victim assistance and other mine–related initiatives. Nonetheless, the report explains, civilian survivors often lack adequate support.

Survivors, local officials and healthcare providers are often poorly informed about the benefits available to landmine survivors. In addition, the benefits can be difficult to access due to paperwork requirements, bureaucratic bottlenecks, and short deadlines for claiming them. Other survivors find that financial assistance, which is provided only in two lump–sum payments, ends up being inadequate to cover some of their basic needs.

Human Rights Watch urged the Colombian government to review and reform its victim assistance programs to address some of these problems.