Summary

In the eastern Colombian province of Arauca and the neighboring Venezuelan state of Apure, non-state armed groups use violence to control peoples’ daily lives. They impose their own rules, and to enforce compliance they threaten civilians on both sides of the border, subjecting those who do not obey to punishments ranging from fines to forced labor to killings. Residents live in fear.

Human Rights Watch visited Arauca in August 2019, documenting a range of abuses on both sides of the border. We interviewed 105 people, including community leaders, victims of abuses and their relatives, humanitarian actors, human rights officials, judicial officials, and journalists. We sent information requests to Colombian and Venezuelan authorities, and consulted an array of sources and documents.

We found that armed groups on both sides of the border exercise control through threats, kidnappings, forced labor, child recruitment, and murder. In Arauca, armed groups have also planted landmines and perpetrated sexual violence, among other abuses.

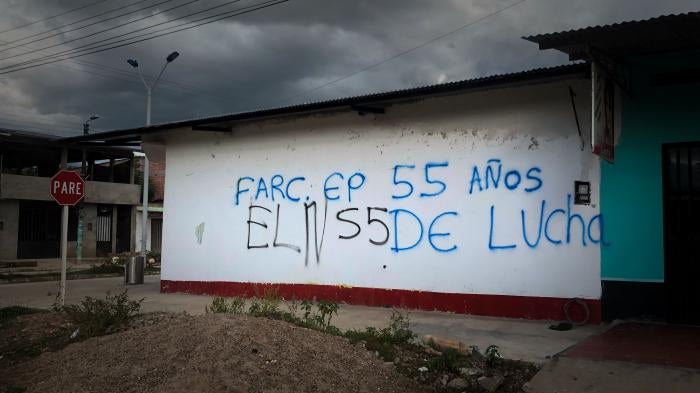

Two armed groups impose social control over the residents of Arauca: the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), a guerrilla group formed in the 1960s, and the “Martín Villa 10th Front” dissident group, which emerged from the demobilized Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP or FARC) after the 2016 peace accord, and sometimes identifies itself as FARC-EP.

These two groups also operate in Venezuela’s Apure state, where the Patriotic Forces of National Liberation (Fuerzas Patrióticas de Liberación Nacional, FPLN) operate as well. This group, whose origins date back to the 1990s, reportedly has a close relationship with Venezuelan authorities in Apure.

The armed groups in both countries have established and brutally enforce on civilians a wide range of rules normally associated with criminal laws enacted and enforced by governments. Members of armed groups do not hold themselves to the same standards. These include curfews; prohibitions on rape, theft, and murder; and regulations governing everyday activities such as fishing, debt payment, and closing times for bars. In some areas, the groups forbid wearing helmets while riding motorcycles, so that fighters can see travelers’ faces. The groups extort money from residents who carry out virtually any type of economic activity.

Some of the armed groups’ rules are included in a 2013 manual of “Unified Rules of Conduct and Coexistence,” which the FARC and ELN created before the 2016 peace accord. Fighters communicate other rules through megaphones or signs posted along roads.

As part of their strategy to control the social, political, and economic life of Arauca, the groups have in recent years increasingly committed unlawful killings, including against human rights defenders and community leaders. In 2015, when the FARC declared a ceasefire to advance peace talks, the government recorded 96 homicides in Arauca. Since then, homicides have gone up, reaching 161 between January and late-November 2019. Armed groups are responsible for the majority of these homicides, according to Colombia’s Institute of Forensic Science and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office.

Human Rights Watch has also received credible allegations of killings by armed groups in Apure, but Venezuelan authorities have not released reliable, comprehensive statistics on killings there.

In 2019, at least 16 bodies of civilians found in Arauca had scrawled scraps of paper on them announcing the supposed “justification” for the killing. The texts accused the murdered victims of being “informants,” “rapists,” “drug dealers,” or “thieves,” for example. Often, the papers were signed “FARC-EP,” suggesting that the Martín Villa 10th Front FARC dissident group claimed responsibility. Residents reported similar killings in 2018.

Armed groups in Arauca and Apure also punish residents with forced labor, requiring them to work for free, sometimes for months, farming, cleaning roads, or cooking in the armed groups’ camps, which are often in Venezuela. Human Rights Watch documented at least two cases of forced labor and received credible allegations of three additional cases. Humanitarian actors, human rights officials, residents, and victims told Human Rights Watch that coerced labor is a common punishment for even minor infractions.

The ELN and FARC dissident group also recruit Colombian and Venezuelan children in both Arauca and Apure, according to human rights officials, humanitarian actors, and residents. Armed groups often offer payment, motorcycles, and guns to children to lure them to join. Girls who escaped from armed groups’ ranks have reported members of the groups committing sexual violence against them, including rape and forced abortion.

Some 44,000 Venezuelans live in Arauca, most having arrived since 2015, fleeing the devastating humanitarian, political, and economic crisis in their home country. Venezuelans in Arauca often live in precarious economic conditions, sleeping on the street or forming makeshift settlements, struggling to earn money, and lacking access to public services such as comprehensive health care. Thousands have also set out on foot from the border region, hoping to reach destinations such as Bogotá, Colombia’s capital. They are often unaware of the dangers along the way, including predation by armed groups.

Venezuelans, many of whom arrive in Arauca from areas without armed groups and who are ignorant of the armed groups’ “rules,” have numbered among the murder victims. Between January and November 2019, the Colombian National Police recorded 30 Venezuelans killed in Arauca. Community leaders, humanitarian workers, and human rights officials told Human Rights Watch that armed groups murdered many of them for violating the “rules.”

Venezuelans have also suffered abuses that are not directly associated with armed groups. Many women are sexually exploited and coerced to sell sex, and often face additional violence. Humanitarian actors have reported cases of human trafficking. Xenophobia in Arauca is notably prevalent and has led to cases of violence against Venezuelans, who are often blamed by local residents for crimes committed there.

Colombian authorities have tried to wrest power from armed groups in Arauca, principally by deploying the military. Several of the military units on duty in Arauca, though, are dedicated to protecting oil infrastructure, which armed groups often attack. In parts of the province, protection of residents is almost entirely lacking.

Security forces are especially ineffective in the countryside. Police presence is often limited to certain urban areas while much of the army presence in rural areas is focused on oil infrastructure. As one police official told Human Rights Watch, in the remaining areas the guerrillas “are the police.”

Protection for human rights defenders, community leaders, and others particularly at risk of attack by armed groups has been limited. Colombia’s National Protection Unit (Unidad Nacional de Protección, UNP) has only one official in Arauca, who is in charge of assigning protection schemes for people at risk. This generates delays and makes it hard to carry out thorough and timely risk assessments. The UNP in Arauca does not itself have protection, or even a car, so is rarely able to visit rural areas.

Security forces in Arauca have also been involved in serious abuses. In one incident in March 2018, soldiers opened fire on four civilians who had gone hunting, killing one of them.

Armed groups appear to feel much freer to operate in Venezuela than they do in Colombia. Groups have at times taken victims kidnapped in Arauca to camps and other facilities they maintain in Venezuela. Rather than combatting them, Venezuelan security forces, as well as local authorities, have colluded with them in at least some cases, according to multiple sources we interviewed, including Apure residents, community leaders, journalists, and humanitarian actors.

Impunity for abuses remains the norm. In Arauca, the Colombian Attorney General’s Office has secured convictions for only eight killings committed since 2017, out of a total of more than 400 now under investigation. None of the eight convictions was of a member of an armed group. Since 2017, the office has not charged, let alone convicted, any member of an armed group for rape, threats, extortion, child recruitment, forced displacement, or the criminal offense of “forcible disappearance,” which under Colombian law covers abductions and involuntary disappearances carried out by armed groups.

The Venezuelan government did not respond to an information request from Human Rights Watch regarding the status of investigations into alleged abuses in Apure. The lack of judicial independence in Venezuela, coupled with widespread fear of reporting crimes, strongly suggests there is little, if any, accountability for crimes committed by armed groups in Apure. Given our sources’ testimony that local authorities and security forces in Apure tolerate and often collude with armed groups, there is no reason to believe that serious investigations into abuses by armed groups have been conducted or will be in the near future.

The implementation of two policies announced in recent years by the Colombian government could decisively influence the human rights situation in Arauca.

In four municipalities of Arauca, the national government has committed to implementing a “Territorial Development Program” (Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial, PDET), an initiative created by the peace agreement with the FARC.

As part of the PDET, residents of the four Arauca municipalities have already participated in designing projects to increase accountability, improve protection for community activists, and address the poverty and lack of educational opportunities that have, for years, made it easier for armed groups to thrive. Implementation of the projects in Arauca could help undermine armed groups’ power and prevent human rights abuses.

On the enforcement side, the government announced in August 2019 a “Strategic Zone of Comprehensive Intervention” (Zona Estratégica de Intervención Integral) for Arauca, which is currently being designed. In such zones, authorities commit to deploying the military alongside police to dismantle armed groups and improve security. Simultaneously, the government aims, in safer parts of these areas, to improve access to public services and strengthen civilian, including judicial, institutions.

Our research suggests that the situation in Arauca is unlikely to improve if the Colombian government continues to focus its strategy on deploying the military without simultaneously strengthening the justice system, improving protection for the population, and taking steps to ensure adequate access to economic and educational opportunities and public services. Conversely, thorough implementation of PDET provisions—especially those related to strengthening the judiciary, protecting community activists, and providing economic and educational opportunities—could help undermine armed groups’ power and prevent further human rights abuses in Arauca.

Increased international pressure on the government of Nicolás Maduro remains key to preventing abuses and ensuring accountability in Venezuela. A United Nations fact-finding mission created in September to investigate human rights violations in Venezuela should scrutinize abuses committed by armed groups in Venezuela with the tolerance or connivance of security forces. Relying on findings by the UN fact-finding mission and other credible sources, international organizations and foreign governments—in the Americas and Europe—should impose targeted sanctions, such as asset freezes and travel bans, on senior Venezuelan officials who have been complicit in abuses by armed groups.

Recommendations

To the Administration of President Iván Duque of Colombia:

To prevent abuses, protect people at risk, and support accountability:

- Include in the policy for the Strategic Zones of Comprehensive Intervention in Arauca a rights-respecting strategy for security forces to protect locals from armed groups, and a plan to remove landmines, starting with the villages covered by the policy.

- Provide greater support to ensure security and protection for prosecutors and investigators in Arauca.

- Strengthen the National Protection Unit in Arauca with more personnel, including as part of the implementation of the so-called “Territorial Development Programs” (PDET).

- Design and implement a plan to prevent child recruitment in Arauca of both Colombians and Venezuelans, and strengthen existing prevention mechanisms in the province, including by ensuring access to education.

- Create a policy that allows members of FARC dissident groups to demobilize and join the individual reintegration program.

- Work with the municipal and provincial governments to ensure that survivors of sexual violence receive the aid and protection to which they are entitled under Colombian law.

- Monitor failures to implement current laws and policies related to gender-based violence in Colombia, with a particular focus on sexual violence perpetrated by armed actors.

- Ensure that the PDET is promptly and fully implemented in Arauca.

To protect the rights of Venezuelans fleeing from the crisis in their country:

- Carry out anti-xenophobia campaigns in Arauca, working with local authorities, civil society groups, and the local population.

- Direct the police in Arauca to take steps to protect Venezuelans who are subject to assault, kidnapping, extortion, child recruitment, rape, murder and other crimes, and hold to account authorities who fail in their duty to enforce the law against those who prey upon Venezuelans.

- Carry out a comprehensive assessment to determine the total number of Venezuelans living in Arauca and their needs.

To the Colombian Attorney General’s Office:

- Increase the number of prosecutors and investigators working in Arauca on cases related to the armed conflict, including homicides, sexual violence, child recruitment, extortion, and threats against human rights defenders and local officials.

- Increase the number of prosecutors and investigators in Arauca working on corruption and collusion between local governments and armed groups.

- Ensure protection for all prosecutors and investigators in Arauca and provide them with adequate resources to carry out their work.

- Create a special unit to investigate possible cases of human trafficking into sexual exploitation and violence and coercion against both sex workers and people forced to sell sex, including Venezuelan women and girls.

To UN Agencies:

- Design and implement plans that include programs to prevent the recruitment of Colombian and Venezuelan children in Arauca and Apure.

- Seek support from international donors to address the needs of the civilian population of Arauca and Apure through a comprehensive plan to provide support to individuals affected by the armed conflict, with a focus on populations at high risk for abuse or exploitation, including—but not limited to—Venezuelans displaced outside their country.

To the UN Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela:

- Investigate collusion by Venezuelan security forces in abuses committed by armed groups in Venezuela, including by the ELN, the FPLN, and the FARC dissident group in Apure, as part of the mission’s mandate to investigate extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions, and torture and other cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment occurring in the country since 2014.

To the US, Canadian, and Latin American Governments and the European Union:

- Impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on senior Venezuelan officials who, according to the UN fact-finding mission and other credible reports by other international organizations, are complicit is abuses by armed groups in Venezuela.

- Assist the Colombian government’s efforts to provide additional humanitarian aid to Colombians and Venezuelans at risk in Arauca.

Methodology

In researching this report Human Rights Watch carried out interviews with more than 105 people. Interviewees included residents of Arauca and Apure, Venezuelan refugees, Colombians who had returned to their country from Venezuela (often called “returnees” in Colombia), human rights officials, judicial officials, human rights activists, victims of abuse and their relatives, members of humanitarian organizations, and Colombian government officials. Members of armed groups were not interviewed for security reasons.

We conducted most of the interviews during a visit in August 2019 to five of the seven municipalities of Arauca: Arauca City, Arauquita, Saravena, Fortul, and Tame. Some additional interviews for the report were conducted by telephone and in Bogotá. All interviews were in Spanish.

The report also draws on a series of official statistics and documents from the Colombian government, publications by international and national humanitarian and nongovernmental organizations, and news articles. We sent information requests to Colombia’s Ministry of Defense, Attorney General’s Office and Victims’ Unit, as well as to Venezuelan authorities. The responses we received are reflected in the report. Venezuelan authorities did not respond.

This report documents abuses committed both in Colombia and Venezuela. Documenting cases in Venezuela presented difficulties. First, Human Rights Watch conducts limited research inside Venezuela due to security concerns. In 2008, a Human Rights Watch team was detained and expelled from the country, with authorities publicly announcing that our presence would not be “tolerated” there. The security situation for our researchers, and anyone else who carries out human rights work in the country, has only worsened since then. Secondly, Venezuelan authorities do not release reliable statistics or information about crimes in the country and, given the lack of judicial independence in the country, there are no reliable statistics from the justice system on investigations, prosecutions, or convictions either. Finally, only a few humanitarian organizations work on issues linked to armed groups in Venezuela.

Most of the interviewees feared for their security and only spoke to Human Rights Watch on condition that we withhold their names and other identifying information. Details about their cases or the individuals involved, including the location of the interviews, were also withheld when requested or when Human Rights Watch believed that publishing the information would put someone at risk. In footnotes, we may use the same language to refer to different interviewees to preserve their security.

Interviews with victims, their relatives, or witnesses were conducted in confidential settings or through secure means of communication. We informed all participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and how the information would be used. Each participant orally consented to be interviewed.

Human Rights Watch did not make any payments or offer other incentives to interviewees. Care was taken with victims of trauma to minimize the risk that recounting their experiences could further traumatize them. Where appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided contact information for organizations offering legal, social, or counseling services, or linked those organizations with survivors.

In this report, “Arauca” refers to the province of Arauca, in eastern Colombia, also referred to as a “department.” We use “Arauca City” or “Arauca municipality” interchangeably to refer to the municipality of Arauca, the provincial capital.

Under Colombian law, private actors as well as state actors can be held accountable for the criminal offense of “forcible disappearances,” defined as any form of deprivation of liberty in circumstances in which those responsible conceal and refuse to acknowledge the fact of deprivation of liberty or give information about the person’s whereabouts.[1] This use differs from the definition in international law of enforced disappearance.[2] This report uses the term “forcible disappearance” to refer to the crime under Colombian law.

Abuses by Armed Groups

Armed groups enjoy significant power and exercise tight control over the population in Arauca and Apure. Members the groups operating there have committed numerous abuses—including unlawful killings, kidnappings, sexual violence, child recruitment, and forced labor—to assert and maintain this control. They have carried out abuses on both the Colombian and Venezuelan sides of the border.

Many of these abuses are violations of international humanitarian law, which is applicable to non-state armed groups as well as national armed forces. Serious violations of international humanitarian law committed with criminal intent are war crimes.

This section of the report details those abuses. To the extent possible, it also provides data on the numbers of killings and other abuses in recent years. Because few people report violence and abuses for fear of retaliation and because Venezuelan authorities have constantly failed to release information on crime rates in the country, the numbers provided below likely understate the extent of the abuses, and in some cases significantly understate it. Our research suggests that countless victims and their families live in silence.[3]

Unlawful Killings

Armed groups have committed unlawful killings in Arauca and Apure.

Unlawful killings are on the rise in Arauca. In 2015, the year in which the FARC declared a ceasefire as part of peace negotiations, the Colombian government reported 96 homicides in Arauca.[4] In 2018, 160 people were killed in the department, a rate of 59 murders for every 100,000 people—roughly two times the national rate.[5] Preliminary statistics from the National Institute of Forensic Science indicate that the numbers continue to rise: 161 people were killed in Arauca between January and November of 2019.[6]

The ELN and the FARC dissident group are responsible for most of the murders in Arauca, as well as for the increase in the murder rates in the province, according to the Ombudsperson’s Office, humanitarian organizations, and the Institute of Forensic Science.[7] According to Colombia’s National Institute of Forensic Science, in 2018, the ELN and the FARC dissident group were thought to be responsible for killing at least 93 people in Arauca, 58 percent of the total that year.[8] The Institute believes that the ELN and the FARC dissident group were responsible for at least 97 killings between January and November 2019, roughly 60 percent of the total.[9]

Venezuelan authorities do not produce comprehensive or reliable statistics on crime rates in the country, making it impossible to determine the full scope of murders by armed groups in Apure state.[10] However, armed groups have also committed unlawful killings in Apure.[11] In September 2018, for example, the ELN reportedly killed the head of the Scientific, Legal, and Criminalistics Investigation Agency (Cuerpo de Investigaciones Científicas, Penales y Criminalísticas, CICPC) in Guasdualito, Apure, after members of the agency allegedly killed a guerrilla commander’s child.[12]

Armed groups in Arauca and Apure often kill those who violate their “rules,” according to multiple sources in Arauca and Apure.[13] In at least 3 cases in 2018 and 16 in 2019 the victim’s bodies in Arauca were found with a piece of paper beside them, stating the apparent justification for the killing: being an alleged “informant,” “rapist,” “drug dealer,” or “thief,” for example.[14] In some cases, the FARC dissident group identified itself as responsible on the piece of paper.[15]

In some cases, victims were found with their hands tied or showing other signs of torture. Colombia’s Institute of Forensic Science told Human Rights Watch that they documented 23 cases of murder with signs of torture—most of which were cases where the victims had their hands tied—between January and mid-August 2019, up from 20 in all of 2018 and 3 in 2017.[16]

Victims of murder in Arauca include Venezuelan exiles. In 2018, according to the National Police, 25 Venezuelans were killed in the province.[17] Preliminary statistics indicate that 30 Venezuelans were killed in Arauca between January and November 2019.[18] Community leaders, humanitarian workers, and human rights officials told Human Rights Watch that many Venezuelans have been killed by armed groups for violating their “norms.” Many of them come from areas where armed groups are not present, so they often do not know these rules exist nor what they are.[19]

In some cases, armed groups first took their Venezuelan or Colombian victims to Venezuela, often to interrogate or “investigate” them before murdering them and leaving their bodies in Arauca.[20] For example, in May 2019, members of the ELN kidnapped Andrés Gómez (pseudonym) in Arauca. His mother went to Venezuela where a commander from the ELN told her that they had taken Andrés there for an “interview” and that he would return home the next day. His dead body was found in one of Arauca’s municipalities, on August 1, 2019.[21]

Armed groups have also killed human rights defenders and community leaders in Colombia. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has documented six cases of human rights defenders—a term it uses in Colombia to include community leaders seeking to promote or protect rights—killed in Arauca between January and late July 2019, up from four in all of 2018 and one in 2017.[22] Four defenders killed in 2019 were working on children’s rights issues; OHCHR and the Attorney General’s Office are investigating whether some may have been killed because they opposed child recruitment.[23] OHCHR and the Attorney General’s Office have indicated that the ELN was responsible for at least one of the murders committed since 2017 in Arauca.[24] Additionally, Alfonso Correa, an Arauca human rights defender, was killed in March 2019 in Casanare, a province south of Arauca. Investigations by the Attorney General’s Office and the OHCHR point to ELN responsibility in this case as well.[25]

|

On April 27, 2018, armed men kidnapped María del Carmen Moreno Páez from her farm in rural Arauquita, Colombia, two relatives told Human Rights Watch.[26] The perpetrators sent her family videos and photos, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, of Moreno Páez blindfolded and demanded money for her release. They killed her hours after kidnapping her. Firemen found her body five days later. Soon after her body was found, a video, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, appeared on social media showing two men, with their hands tied and chains around their neck, who confessed to the kidnapping and murder of Moreno Páez. Later that same day, the dead bodies of the two men were found in a town called El Troncal; a note on the bodies read: “These are the authors of the kidnapping and killing of María.… We are applying justice. FARC-EP. The people’s army.”[27] |

|

Mauricio Lezama, a filmmaker working on a documentary about victims in Arauca, was drinking juice in front of a small shop in La Esmeralda, a town in rural Arauca, on May 9, 2019, while he waited to start filming a documentary, when two men on a motorcycle drove by and shot him. The shooting killed him instantly and wounded another person.[28] His body lay on the street for hours until authorities were able to come and remove it.[29] It is unclear who killed Lezama, though investigations by the Attorney General’s Office and the OHCHR indicate that the FARC dissident group appears to be responsible.[30] |

Child Recruitment

The FARC dissident group and the ELN recruit Venezuelan and Colombian children in Arauca and Apure. Some recruited children are as young as 12 years old.[31] Credible sources told Human Rights Watch that both armed groups have established camps in Apure, where they train new recruits, including children.[32]

While Venezuelan authorities do not produce reliable statistics on child recruitment, the Victims’ Unit in Colombia registered 14 cases of child recruitment in Arauca between 2017 and 2019.[33] Colombia’s Attorney General’s Office is investigating 21 cases of child recruitment committed since 2017 in Arauca, including 6 victims who were Venezuelan.[34] Yet there is significant under-reporting of child recruitment, according to a humanitarian source, two human rights officials, and a government official who works on the issue.[35] Indeed, a government official and a humanitarian organization reported the recruitment of 15 children by the FARC dissident group in the municipality of Saravena alone between January and March of 2019.[36]

Child recruitment by the FPLN appears to be uncommon, according to local community leaders, journalists, and researchers in Apure.[37] Human Rights Watch did not document any such cases.

The ELN and the FARC dissident group offer children payment if they join, as well as access to motorcycles and guns, according to humanitarian actors, and community leaders.[38] Human Rights Watch received messages from community leaders in Apure through a local reliable source, in which the leaders stated that Colombian armed groups recruit children in the state.[39] One of the leaders said the ELN organized soccer games to convince children to join the group’s ranks.[40]

Children are recruited to be full-time fighters, living in guerrilla camps and taking part in combat, or to be militia members, living in urban areas and collecting extortion payments, providing information for their rural counterparts, and carrying out small-scale violence, such as grenade attacks.[41]

Humanitarian actors in Arauca who have had some form of contact with the armed groups also report that children make up part of the ranks of both armed groups.[42] In July 2019, 16 members of the FARC dissident group in Arauca handed themselves over to the Armed Forces; six of them were under the age of 18, including one Venezuelan. Almost all of the demobilized fighters were from an indigenous community.[43]

Children recruited by the FARC dissident group face a precarious situation if they want to escape from the armed group once they become adults. Under Colombian law, there is no legal route if adults wish to demobilize and, unlike ELN fighters, they are not eligible for reintegration programs.[44]

The FARC dissident group has retaliated against members who have tried to escape. One witness to FARC dissident abuses inside a camp in Venezuela said he saw a “revolutionary trial” in which the group tried two fighters—an adult and a child—for trying to escape. He told Human Rights Watch that the fighters voted to kill the adult but gave the child a “second chance” and imposed a sanction that consisted of forcing him to dig trenches.[45] In August 2019, the army rescued a 2-year-old boy who had been kidnaped by the FARC dissident group in Arauca in April. He is the son of two fighters who had escaped from the group’s ranks and had apparently been kidnapped in retaliation for their escape from the group.[46]

|

Lina and Natalia (pseudonyms), both 15, took the bus home from school one day in rural Arauca in April 2019. When they got off the bus, ELN members convinced them to go to a guerrilla camp to become fighters. Lina’s mother, along with another community leader, went to the camp as soon as she found out what had happened. There, she was able to convince the commander to let her daughter go, but he did not release Natalia. The commander stated that if Lina ever came back to the guerrillas, she would stay there for life. According to government officials who spoke with Lina, guerrilla members asked the two girls if they were virgins, and took pictures of them in their underwear. Both Lina and her mother later fled Arauca.[47] |

Kidnappings, Forcible Disappearances, and Forced Labor

The ELN and FARC dissident group in Arauca and Apure kidnap civilians, including to subject the victims to forced labor as a punishment for violating the groups’ “rules.”

Since 2017, 24 people have been kidnapped by armed groups in Arauca, including 13 in 2018 and 5 between January and September 2019.[48] These include cases in which armed groups demanded extortion payments or subjected the victims to forced labor. Victims include members of the Colombian armed forces.[49]

In Apure, the ELN, and the FARC dissident group kidnap people mostly to force them to carry out forced labor, according to journalists, residents, a human rights activist, and researchers.[50] Armed groups in Apure also kidnap farmers so they can take over their land.[51]

The number of people who have gone missing has increased in Arauca over the past two years. According to Colombia’s Institute of Forensic Science, the reported number of missing people in the province increased from eight in 2017 to 14 in 2018.[52] The Institute reported that 12 people went missing in Arauca between January and November 2019.[53] Under Colombian law, private actors as well as state actors can be held accountable for the criminal offense of “forcible disappearances”[54] and the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that, as of September 2019, prosecutors had pending investigations into 46 cases of alleged forcible disappearance committed in Arauca since 2017.[55]

Some of the people reported missing have reappeared after months of forced labor in farms or guerrilla camps—a form of punishment imposed by armed groups in Arauca. [56] Largely in an effort to impose social control, armed groups force people who violate “norms” to work in their camps or on farms reportedly run by people linked to them.[57]

Human Rights Watch documented two cases, described below, of forced labor—one by the ELN and another by the FARC dissident group—and received credible allegations from humanitarian actors and locals about three more.[58] In both cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the victims stated that they saw or spoke with other people who were also forced to work in the places the armed groups were holding them. In both cases, the victims were held in Venezuela, where they were subject to forced labor. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, Colombian and Venezuelan authorities do not maintain an official record of cases of forced labor, though local observers believe this form of “punishment” by armed groups is more commonly implemented by the ELN than by other armed groups.[59]

Victims of forced labor are not always kidnapped. For example, Human Rights Watch received credible allegations that in late 2017 a group of young men who an armed group accused of robbery was forced to clean up parts of their own town in Apure.[60]

|

Miguel Escobar (pseudonym), a 31-year-old Venezuelan man, told Human Rights Watch that in May 2019 he was summoned to a FARC dissident camp in Venezuela to speak to “Jerónimo,” the FARC dissident group commander. Escobar’s wife had told the FARC dissident group that he had mistreated her, he said. Escobar told Human Rights Watch that after a short discussion with “Jerónimo,” he was forced to work without pay as a cook in the dissident camp for two months. In the camp, he worked with two other civilians who were subjected to the same treatment, he said. Miguel witnessed one murder and received first-hand accounts about four others while he lived in the camp, he said. After he had “served” his two months in the camp as a cook, one commander told him that they were planning to hold him there for two years. Miguel escaped shortly thereafter.[61] |

|

Carlos Torres (pseudonym) was at a bar in Arauca in late 2017, where he said he had a small altercation with a young man. The next day, a car pulled up in front of his house; a young man got out, knocked on the front door, and then forced his way into Carlos’ home along with three others. All four were armed, Carlos noted. They forced him into the car, blindfolded him, and later put him in a canoe, taking the canoe across the Arauca River into Venezuela, he recalled. There, he worked on a farm for nearly seven months, he claimed, doing various jobs with two other young men. Eventually, when he was released, his captors revealed that they belonged to the ELN and said they had brought him to do forced labor because the young man he had a problem with at the bar was an ELN fighter. He moved elsewhere after the ELN threatened him after he was released.[62] |

|

Luis Menendez (pseudonym) was kidnapped in Arauca in 2019. That night, he had been at a bar with friends when six armed men arrived. The men said they were FARC dissidents, he recounted, and told him he had to go with them. After he initially refused to go, the men fired two shots at the floor. Menendez told Human Rights Watch that they then brought him to the Arauca River and crossed over to Venezuela. Once in Venezuela they drove him to a house, passing through two checkpoints of the Bolivarian National Guard (Guardia Nacional Bolivariana) of Venezuela without being stopped, he said. Days later, when the FARC dissident group realized his family would not be able to pay the ransom they had requested, they let him go.[63] |

Threats and Other Forms of Social Control

Armed groups in Arauca and Apure routinely threaten people to ensure social control. These threats are often directed against people who violate the groups’ “rules” or to pressure civilians to do as the groups want.

Colombia’s Victims’ Unit registered more than 2,000 threats related to the armed conflict in Arauca between 2017 and September 1, 2019.[64] “It’s like there are two forms of government,” one human rights activist in Apure told Human Rights Watch. “They [the armed groups] threaten you twice and the third time is a death sentence.”[65]

Threats can come in multiple forms. For example, both the FARC dissident group and the ELN make threats through pamphlets, announcing “social cleansing” —a term used in Colombia and in Venezuela’s Apure to describe the killing of certain people considered “undesirable” for society, including thieves and drug addicts.[66] These threats occur both in Apure and Arauca.[67]

These pamphlets are consistent with the manual of “Unified Rules of Conduct and Coexistence” created by the FARC and ELN in 2013 after they ended their 2006-2010 conflict. The manual includes rules for both guerrilla fighters and locals.[68] The “norms” in the manual, which the ELN and the FARC dissident group continue to apply,[69] are designed to control numerous aspects of daily life: they regulate fishing; prohibit rape, theft, and murder; mandate timely debt payments; and even specify when bars should close. The manual also obliges community members to work one day a month in a community task.[70] While the manual includes references to “exemplary punishment” and “adequate response” to “serious crimes,” it does not specify the punishments to be imposed for violating the rules. In practice, however, these punishments include death, forced labor, threats, and displacement.

While armed groups apparently do not apply the manual in Apure, Venezuela, the punishments they mete out for comparable “infractions” are the same. The three armed groups operating in Apure punish locals for not following the “rules,” including through threats, forced labor, and occasionally murder.[71]

Several humanitarian aid workers, human rights officials, and activists told Human Rights Watch that it is more common for the ELN to use pamphlets or threaten people before killing them, while the FARC dissident group tends to kill its victims without warning.[72]

Government officials are also often threatened, at least in Colombia.[73] Five out of seven heads of local personerías—municipal human rights offices—in Arauca have been threatened by armed groups, and some have fled the province.[74]

Politicians, including some who ran for governor, mayor, and the municipal council in the October 2019 local elections in Colombia, have also received threats from armed groups.[75] In a pamphlet in February 2019, for example, the FARC dissident group threatened members of the Democratic Center party, the party led by former President Álvaro Uribe and current President Iván Duque.[76] Colombia’s Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office has stated that four of the seven municipalities in Arauca present an “extreme” —the highest—level of risk for electoral violence.[77] It has noted that the city of Arauca is the municipality in Colombia with the highest number of human rights violations against people who work on electoral campaigns or are candidates themselves.[78]

Armed groups often require people to go to meetings with commanders, where they can be threatened as well.[79] It is common for groups in Arauca to hand over to victims handwritten notes on small pieces of paper with the armed group’s logo, called “vikingos” (the Spanish word for “vikings”), calling them to a meeting with a commander.[80] On other occasions, some people have been told that they have to meet with an armed group by someone who approaches them in public.[81] For example, Human Rights Watch interviewed a politician who received two notes from the ELN. In November 2018, the group extorted him for cash; in July 2019, the ELN demanded he appear at a specific point for unstated reasons.[82] A member of the group had previously told him that he should do as they say.[83]

These meetings take place on both the Venezuelan and Colombian sides of the border.[84] One community leader told Human Rights Watch that he had to cross the border to Venezuela for a meeting, where commanders of the FARC dissident group and the ELN were present. In the meeting, the commanders explained to him the groups’ concerns about some government initiatives in his town. According to the leader, who said he had been previously threatened three times by the armed groups, “it would be too dangerous not to go” to the meeting.[85]

In rural areas of Arauca and Apure, armed groups place signs in the streets or use megaphones to communicate their rules to local residents or make public announcements about government policies or programs.[86] Some, for example, set curfews in rural areas and forbid people to wear helmets while riding motorcycles so that fighters can see their faces.[87] Ironically, a community leader told Human Rights Watch that “using a helmet can be dangerous.”[88]

Armed groups in Arauca and Apure also engage in widespread extortion. Virtually everyone in the province has been a victim of extortion, including poor farmers, according to interviews by Human Rights Watch.[89] “We don’t produce enough to feed our families and we have to pay [them],” a local farmer told Human Rights Watch.[90] Nonetheless, few victims appear willing to report such extortion. While multiple sources told Human Rights Watch that extortion is widespread in Arauca, Colombia’s Attorney General’s Office is currently investigating only 263 cases allegedly committed since 2017.[91] Similarly, the Defense Ministry has registered 285 cases of extortion between 2017 and late-September 2019.[92]

The ELN and the FARC dissident group separately extort people in the same areas and sometimes demand the same amount of money, but it is often unclear whether or when the groups expect residents to pay both. A victim of extortion and a human rights official told Human Rights Watch that people do not have to pay both groups,[93] but two residents told Human Rights Watch that they had been forced to do so. [94] As mentioned above, some people are summoned to meetings in Venezuela to make such payments.[95]

|

Viviana Sánchez (pseudonym) owned a small shop in rural Arauca. Colombian Army soldiers would occasionally patrol the hamlet and stop in her shop, she told Human Rights Watch. The ELN threatened her because of her contact with the soldiers, she said. She told Human Rights Watch that a low-level guerrilla fighter would often go to her store, drink beer, and make unwanted sexual advances against her, which she consistently rejected. In July 2019, she received a pamphlet saying she had to leave the hamlet. She went to meet with the commander in the area, she recounted, where a guerrilla fighter put a pistol against her head as another one asked her various questions about her relationship with the soldiers. She was allowed to stay in the village under certain conditions, such as no longer selling anything to members of the Army. Soon after, the fighter who had sexually harassed her rose in the ranks in the area, and went back to her shop to drink, and she once again rejected his unwanted sexual advances. An ELN militia member whom she knew later told her that her harasser had ordered her killing because she had rejected him, and said the order included that she be killed in front of her daughter and that the killing be filmed. Sánchez fled the village with the help of the same ELN militia member and was afraid of returning when Human Rights Watch interviewed her.[96] |

Sexual Violence

Armed groups have committed numerous acts of rape and other sexual violence. Colombia’s Victims’ Unit registered 25 cases of sexual violence linked to the armed conflict in Arauca between January 2017 and September 2019.[97]

A humanitarian source told Human Rights Watch about a case in which a woman was kidnapped by the ELN in Arauca and taken to Venezuela, where members of the guerrillas raped her. They then brought her back to Colombia and threatened to rape her daughter, whose age Human Rights Watch was not able to ascertain, if she did not pay a debt she owed the group.[98]

Humanitarian actors told Human Rights Watch that girls as young as 14 years old in armed groups’ ranks are often subject to sexual violence and abuse.[99] For example, a 15-year-old Venezuelan girl who escaped from the FARC dissident group in 2019 told authorities that her commander raped her.[100] Similarly, a 14-year-old girl who escaped in August 2019 from an armed group that was holding her in Venezuela reported that the group’s fighters raped her, as described below.[101]

|

Carolina (pseudonym), 14, was recruited in early 2019 by an armed group operating in Arauca and was taken to Venezuela. A few months later, she escaped and made it back to Colombia. She told humanitarian actors that she had been recruited to be a fighter and was raped by various members of the armed group. During her time with the group, she became pregnant. She said that members of the armed subjected other girls in the group to sexual violence, including rape and forced abortions.[102] |

While all of the different types of abuse documented in this report are likely undercounted for the reasons noted above, a number of specific factors contribute to what is likely significant underreporting of sexual violence. In a 2012 report on gender-based violence in Colombia, Human Rights Watch identified a range of obstacles displaced women and girls faced when seeking justice after gender-based violence, including mistreatment by authorities, evidentiary challenges, poor referrals, economic barriers, and fear of reporting.[103]

Landmines and Explosives Attacks

The 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, to which Colombia is a party, comprehensively bans antipersonnel landmines.[104] The armed groups have continued to plant landmines in Arauca.

According to Colombian government statistics, 23 people have been wounded by landmines in Arauca, including 10 civilians and 13 members of the Armed Forces, since 2017.[105] The ELN has publicly acknowledged that it uses antipersonnel mines in Arauca, though it claims only to do so against state forces.[106] Yet landmines are inherently indiscriminate weapons, meaning that when using them, armed forces and armed groups cannot differentiate between civilians and combatants. A humanitarian actor and a community leader who works with landmine victims reported that the FARC dissident group also plants landmines.[107]

ELN and the FARC dissident group in Arauca also carry out attacks with bombs and mortar-like gas cylinders filled with explosives. The police reported that between 2017 and September 2019, armed groups carried out 85 attacks with explosives in Arauca, including 63 in 2019.[108] Armed groups do not appear to carry out this type of attack in Apure.[109]

These weapons are indiscriminate and unlawful when used in civilian populated areas. In July 2019, an armed group wounded three civilians, including a girl, during a cylinder bomb attack on a military base in Saravena.[110] In August 2019, members of an armed group left a bomb behind the Fortul police station, in the town center. Four civilians were injured, including a 4-year-old girl.[111]

|

Alexis Torres, 42, and his wife were driving in their car along the road that connects Saravena to the nearby town of Cubará, on March 1, 2019. As they drove along, they noticed a group of soldiers along the side of a bridge. Upon driving up onto the bridge, a bomb placed by an armed group exploded under it.[112] Their car was destroyed. Torres suffered severe wounds on his face and a fractured skull, while his wife suffered minor injuries, Torres told Human Rights Watch. Torres required two surgeries to repair his face and skull, while his wife suffered severe psychological effects from the explosion.[113] |

Forced Displacement

Forced displacement of civilians is less visible in Arauca than in many other areas of Colombia because mass internal displacement is relatively rare.[114] According to Colombia’s Victims’ Unit, 2,366 people were forcibly displaced from their homes in Arauca in 2018, up from 1,684 people in 2017. Preliminary data shows that over 1,100 people were forcibly displaced between January and August 31st, 2019.[115]

Leading causes of forced displacement in Arauca and in Apure include the killing of a family member, threats, and extortion.[116] If someone does not obey the rules, “he must leave or [he will] die,” a community leader told Human Rights Watch.[117] As mentioned above, there are credible allegations that armed groups in Apure forcibly displace farmers in order to steal their land.[118]

|

Rafael Ortíz (pseudonym), 20, worked with a local community organization in Arauca. He told Human Rights Watch that as the organization grew in visibility, the armed groups in Arauca began to pay attention to him. In early 2019, FARC dissidents called him, saying he would be held to account if any member of his organization got out of line. Later, members of the ELN forcibly took him to a village in rural Arauca, he said, where a commander offered him $700,000 Colombian pesos (about US$210) for every child 12 years old and over that he recruited for the group. When he rejected the offer, the commander told him that he would have to “face the consequences.” Ortíz left the meeting and fled Arauca immediately after.[119] |

Venezuelan Exiles in Arauca

Venezuelan Forced Migration to Colombia

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) more than 4.7 million Venezuelans have fled their country in recent years.[120]

By official counts, as of October 2019, roughly 1.6 million Venezuelans lived in Colombia.[121] The number may be much higher, given that many use the more than 300 irregular crossings along Colombia’s border.[122]

The Colombian government has adopted a series of measures to provide arriving Venezuelans access to health care for urgent needs and to enroll Venezuelan children in schools. Other initiatives, in coordination with UN agencies and local humanitarian groups, provide meals, vaccination, and shelter, amongst others.

The Colombian government created a special permit, known as “Special Staying Permit” (permiso especial de permanencia), which allows Venezuelan citizens who enter the country legally but overstay their visas to regularize their status and gain work permits and access to the social security system.[123] In total, Colombian authorities granted this permit to over 740,000 Venezuelans between July 2017 and July 2019.[124]

Venezuelan Forced Migration to Arauca

Roughly 44,000 Venezuelans currently live in Arauca province; the vast majority crossed the border since 2015.[125] Poverty and lack of access to basic services make many of them vulnerable to abuse, while their lack of familiarity with rules imposed by armed groups is often the direct cause of being victimized.

Hundreds of Venezuelans also transit through the province every day, many of them walking to other parts of Colombia.[126] One humanitarian actor reported that they had given aid to over 7,000 Venezuelans walking along the roads in Arauca in a period of five months in 2019.[127] Many of them do not know how far their final destination is, nor the difficult terrain and weather conditions they may face along the way.[128]

Many Venezuelans in Arauca City live in informal settlements, without access to basic services such as running water.[129] Some of these settlements were created over a decade ago by internally displaced populations and are controlled by armed groups, which impose their rules and recruit Colombians and Venezuelans.[130] Other Venezuelans sleep in the streets or by the banks of the Arauca river. [131]

Access to health services is also very limited for Venezuelans in Arauca. The Colombian government grants all Venezuelans free access to emergency health services. Yet in Arauca hospitals often interpret this provision narrowly, limiting Venezuelans to only some emergency health services.[132] Venezuelans who have a “Special Staying Permit” are eligible for subsidized health insurance, but, as with Colombians, the process to obtain the health insurance is slow.[133] Additionally, in Arauca, the health system does not have sufficient capacity and resources to attend to the increasing influx of Venezuelans, who often resort to international humanitarian organizations for aid.[134]

Many desperate Venezuelan women engage in sex work in Arauca.[135] And many Venezuelan girls are sexually exploited and abused. Two humanitarian sources estimate that over 90 percent of female individuals selling sex in the department are Venezuelans.[136]

While the Colombian Attorney General’s Office is not currently investigating any cases of human trafficking occurring in Arauca at least since 2017, Human Rights Watch received credible allegations from humanitarian actors about several such cases of trafficking into sexual exploitation.[137] Victims are tricked or forced to sell sex. In some cases, once they arrive at a brothel in Arauca, their documents are withheld, and they are given clothes, food, and “housing” which they must pay for through their work. The amounts they are charged can be so exorbitant they will never be able to pay off the debt.[138]

Xenophobia against Venezuelans is particularly prevalent in Arauca.[139] Several Colombian interviewees expressed xenophobic sentiments while talking to Human Rights Watch, including by blaming Venezuelans for an increase in crime rates in Arauca and suggesting that is why more Venezuelans are getting killed by armed groups.[140]

In one incident in November 2018, locals accused a Venezuelan man of killing a shop-owner in Arauca City. The day after the killing, a group of locals joined up and physically and verbally attacked Venezuelans living on the street. According to humanitarian and human rights sources with direct knowledge of the case, the police did not intervene to prevent the violence against Venezuelans.[141] Various Venezuelans in Arauca told Human Rights Watch that members of the Colombian police verbally and even physically abused them, insulting or hitting them, or destroyed their belongings.[142]

Protection and Accountability in Colombia

Accountability

Authorities in Arauca fail to provide justice for victims of abuses committed by armed groups. Their failure to do so, coupled with more general policing failures, also contributes to the perception among some residents of Arauca that armed groups are more “effective” than the government in solving problems among residents.[143]

The Attorney General’s Office reported to Human Rights Watch that, as of September 2019, it was investigating 422 cases of murder committed in Arauca since January 2017.[144] Prosecutors had indicted 78 people, including five ELN members, and secured just eight convictions, none of which were against members of armed groups.[145] The office reported it had not charged, let alone convicted, any member of armed groups for child recruitment; threats intended to cause alarm, anxiety, or terror in the community; forcible disappearance; forced displacement; extortion; or rape committed since January 2017.[146]

One of the main challenges is limited staff. Prosecutors who work on crimes such as threats, homicides, and sexual violence (known as “sectional prosecutors”) often have hundreds and, at times, thousands of cases.[147] A prosecutor who had over 2,000 cases showed a Human Rights Watch researcher 24 boxes with active cases, and said she did not know what they are were about, due to the large volume of cases she handles. [148] In Saravena, there are just two prosecutors investigating murders, threats, sexual violence, and other serious crimes.[149] In Tame, there are five prosecutors, two of whom investigate crimes such as homicides and sexual violence: one has 900 cases; the other has 700.[150]

In addition to the prosecutors listed above, at least two other prosecutors in Arauca province are based inside Army battalion facilities: one in Arauca and one in Saravena.[151] They belong to the regular justice system (not the military justice system) and investigate serious crimes, such as homicide. Two judicial authorities told Human Rights Watch that one of the main areas of focus of these two prosecutors is crimes committed against the oil pipeline.[152] In recent years, the Attorney General’s Office has signed several agreements with the state-owned oil company Ecopetrol in the area, whereby the company pays to receive “special attention” by prosecutors, including the “prioritization” of crimes against the company such as bombings against the pipeline or oil infrastructure in general, and theft of oil.[153]

The number of prosecutors investigating crimes with lighter punishments (known as “local prosecutors”) is also limited. They handle such crimes as robberies, domestic violence, failure to pay child support, and injuries.[154] There is only one prosecutor in Arauquita and another in Fortul; each of their teams are composed solely of one assistant.[155]

The number of investigators that support the work of prosecutors is also insufficient. In six of the seven municipalities of Arauca, there are no investigators of the Technical Investigation Unit (Cuerpo Técnico de Investigaciones, CTI)—the body charged with providing investigative and forensic support to prosecutors in criminal cases—to assist them.[156] So prosecutors have to rely on police investigators, who often carry out multiple roles that go far beyond investigating, such as aiding in captures or standing guard at the police station.[157] In Tame and Saravena, there is only one police investigator per prosecutor.[158] In Arauquita, there are just two police investigators.[159] In Fortul, there are no police investigators, so the prosecutor has to request support from police investigators working with other prosecutors in Saravena, who, at times, take between three and four months to respond.[160]

Security risks undermine prosecutors’ and investigators’ ability to investigate crimes. Traveling to rural areas is extremely risky, and most investigators simply do not go, unless they are accompanied by military personnel.[161] In some urban areas, such as Tame and Saravena, investigators do not go to certain neighborhoods due to security concerns.[162] In the words of one official, “[e]very day, I come straight from my home to the office, and go straight from the office, home.”[163] In rural areas in Arauca, funeral homes, not forensic experts, carry out the removal of bodies.[164] This can lead to destruction or improper handling of evidence and it too impedes prospects for serious investigations.

Protection for authorities is extremely precarious. One prosecutor told Human Rights Watch that because the Attorney General’s Office has not made a car available for him when he has to travel to neighboring municipalities for hearings, he takes a shared taxi in which anyone can ride with him.[165] Another prosecutor had received written instructions from his superiors to avoid leaving his home due to security risks. But in another letter from the Attorney General’s Office, he was instructed to visit crime scenes despite the security risks and lack of a protection scheme.[166]

A shortage of judges also undermines the government’s capacity to pursue criminal offenses and abuses by armed groups in Arauca. In Saravena, there are only two judges; a third, the sole judge for criminal cases in the city, was moved to Arauca City in 2019 after she was attacked with a grenade.[167] In Tame, there is one judge, who must hear every case in the municipality, including hundreds of “tutelas,” lawsuits any citizen can present before authorities to protect their rights.[168] We were told that cases ready to go to trial in August 2019 would be heard only in March or April 2020.[169]

Underreporting of abuses is extremely common in Arauca, given armed groups’ tight control and residents’ fear of being seen as collaborating with the government, as mentioned above.[170] Venezuelans there also fear reporting the crimes against them due to fear of being deported, according to humanitarian sources.[171] Underreporting may help give the impression that the situation in Arauca is not as troubling as it really is. “What really counts are the complaint records,” a police official told Human Rights Watch, “and there are no complaints here, so it appears that nothing happens.”[172]

Security Response and Abuses by Security Forces

The Colombian Army and National Police have failed to adequately protect residents in Arauca and ensure security in the province. Under Colombian law, the responsibility to protect the population rests primarily with the police, while the armed forces are largely charged with combating armed groups.[173]

The XVIII Brigade of Colombia’s Army and the Quirón Task Force—a unit charged with combating the ELN and the FARC dissident group—operate in the province.[174] Yet many soldiers are not tasked with protecting the local population. Six of the twelve units of the XVIII Brigade are charged with protecting oil infrastructure, including five “Special Road and Energy Battalions,” military units specifically mandated to protect oil and other infrastructure.[175] Like the Attorney General’s Office, the Defense Ministry has signed several agreements with oil companies in the area, in which the companies pay to receive “special attention” from the Army in Arauca.[176] Recently, authorities announced that a unit of the Army that works in urban areas will soon begin operating in Arauca as well.[177]

The police have stations in the urban center of each municipality, as well as in two towns in rural Arauca.[178] They rarely venture into the countryside. In some places, like Fortúl and Saravena, police are frequently attacked by armed groups.[179]

A police official in one Arauca municipality described the situation as follows: the 30 police in the city only patrol two or three blocks, the Army is focused on protecting oil infrastructure and roads, and in the rest of the territory “the other police,” meaning the guerrillas, “rule.” “They are the police,” he said. [180]

In August 2019, President Duque launched a new security policy called “Future Zones,” or “Strategic Zones for Comprehensive Intervention.” The government designated five such areas—Arauca province is one—where it will prioritize sending military and police forces to “confront and dismantle criminal networks,” creating a basis for strengthening Colombian civilian institutions in the future.[181] Within these five areas, the government will identify the most dangerous villages where the presence of military and police forces will be prioritized. In villages deemed less risky, plans to develop civilian institutions, related to education or agriculture, for example, may begin.[182] The policy, however, has yet to be implemented in Arauca.[183]

There is credible evidence that the Army in Arauca has been involved in serious abuses. In March 2018, for example, soldiers opened fire on four civilians who had gone hunting, killing Ciro Alfonso Manzano Ariza and wounding Andrés Fabián Salcedo Rincón.[184] One witness told Human Rights Watch that the soldiers accused the men of being guerrillas.[185] Survivors were detained for two days until a judge ordered their release because the soldiers’ accounts of events were inconsistent.[186] In October 2018, the Attorney General’s Office charged one officer and seven soldiers with “aggravated homicide” and “attempted homicide.”[187]

There is also credible evidence of instances of police abuse. As mentioned above, various Venezuelans in Arauca told Human Rights Watch they had been verbally and even physically abused by some members of the Colombian police, and credible sources said police failed to protect Venezuelans when local residents attacked them.[188]

Protection of People at Risk

Community leaders and human rights defenders have been targets of both the ELN and the FARC dissident group in Arauca.

Many officials and community leaders have some sort of protection scheme provided by Colombia’s National Protection Unit (Unidad Nacional de Protección, UNP). These can include bulletproof vests, cellphones, vehicles, and, in extreme cases, bodyguards.[189] In Arauca, the protection schemes themselves have been targeted by armed groups. Between August 2018 and December 2019, armed groups stole at least seven vehicles belonging to the UNP. The FARC dissident group was allegedly responsible in most cases.[190] In August, young men claiming to be members of the FARC dissident group arrived at an activist’s house, and at gunpoint stole the UNP car he shared with 14 other members of a local organization.[191]

The UNP has only one official in Arauca, so UNP officials must travel from Bogotá or other cities to assess the risk faced by people in Arauca. This generates delays and makes it harder to carry out a thorough analysis because they are less knowledgeable about the situation in Arauca, a government official told Human Rights Watch.[192] When UNP staff are in Arauca they do not have protection, or even a car, so most risk analyses are carried out in urban areas.[193] They also lack sufficient funds to implement security schemes in cases of emergency. [194]

Government efforts to protect children at risk of recruitment have also been insufficient. Some children who escaped from armed groups have later been killed or recruited again back into the armed groups, various sources said.[195] One former child combatant was killed by the FARC dissident group after he left the group and was living in a village in rural Arauca.[196] In another case, a young girl who had left the FARC as a child in 2015 returned to the province in late 2018 after the peace deal, believing she would be safe. The FARC dissident group kidnapped her in December 2018, submitted her to a “revolutionary trial,” found her “guilty” of having deserted, and then killed her.[197]

Local Development Programs

Armed groups have taken advantage of lack of effective governance in Arauca—including lack of state presence in rural areas—to exert their authority in the province. Poverty and the lack of work and educational opportunities, especially in rural areas, facilitate recruitment by armed groups in Arauca.[198]

Historically, the guerrillas have used the lack of state institutions in the countryside to instill their own order, resolving conflicts between local residents and imposing their own rules where the state does not enforce the rule of law.[199] The ELN and FARC dissidents continue to take advantage of these conditions.[200]

A key government policy to address these historic governance weaknesses are the “Territorial Development Programs” (PDET).[201] These programs, created under the peace accord with the FARC, allow local citizens to help create plans to improve state and economic development in their regions. The first step is a design phase for PDETs with citizen participation that is intended to create an overall plan to ensure greater state presence and legitimacy. [202] Once local communities and the national government agree on the plans, the government has to implement them over the next 10 to 15 years.[203]

One PDET covers four municipalities in Arauca: Saravena, Tame, Fortúl, and Arauquita. Between September 2017 and July 2018, the government organized a series of meetings with local residents that led to various initiatives to stimulate local development and improve community well-being.[204] Residents proposed initiatives to improve access to education in the countryside, in part because it would help undermine armed groups’ ability to recruit children. The government also agreed to carry out measures to improve access to basic services, such as water and sanitation, and to increase and improve economic opportunities for people living in rural areas, including by paving roads or investing in economic projects and businesses.[205] Other plans included in the PDET address shortcomings identified throughout this report, including the need to strengthen the capacity of the Attorney General’s Office and the judiciary, as well as to improve security measures for community leaders.[206]

In December 2019, the government said it had begun to implement some PDET projects in Arauca.[207]

Protection and Accountability in Venezuela

Complicity of Venezuelan Authorities in Armed Group Abuses

The ELN and the FARC dissident group appear to feel safer and more open to operate in Venezuela than they do in Colombia. [208] The ELN and the FARC dissident group maintain camps in Apure, multiple credible sources told Human Rights Watch.[209] And, as shown above, both armed groups often take their victims to Venezuela or summon them to meetings there.

Many sources told Human Rights Watch that government security forces and local authorities in Venezuela tolerated and at times colluded with armed groups.[210] These sources included residents, journalists, researchers, community leaders, security experts, and a human rights activist. “Sometimes it’s unclear if local mayors control the FPLN or if the FPLN controls mayors,” said a researcher from a Venezuelan security think-tank.[211]

Human Rights Watch obtained information suggesting complicity of Venezuelan authorities in abuses by the ELN, the FARC dissident group, and the FPLN.[212] One victim of kidnapping reported passing through two checkpoints of the Bolivarian National Guard in Apure without any hindrance.[213] In one check point, the FARC dissident group members were hooded and carrying assault weapons. Similarly, credible sources indicated that members of the Bolivarian National Guard work together with armed groups to extort people taking goods across the border.[214] Officials also tolerate likely abusive activities without taking action: another victim reported being in a large FARC dissident camp very close to a Venezuelan military base for more than two months without any interference by Venezuelan authorities.[215]

Human Rights Watch sent a letter to Venezuela’s Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza requesting information on the alleged presence of armed groups in Venezuela and what policies were being put in place to protect the population from abuses. We had received no response at time of writing.

Accountability

Unlike in Colombia, where a body of relevant data is publicly available and authorities generally respond to requests for information, Human Rights Watch is unable to closely assess what measures, if any, Venezuelan authorities are taking to provide justice for victims of abuses by armed groups in Apure state. Government data is not available and, as noted above, Venezuelan authorities have not responded to our requests for information on investigations and prosecutions. There are indications, however, that accountability for abuses by armed groups in Apure may be minimal, if not absent altogether.

First, there is no judicial independence in Venezuela. After the political takeover of the judiciary by then-President Hugo Chávez and his allies in the National Assembly in 2004, the justice system stopped functioning as a check on executive power. Currently, judges and officials within the Attorney General’s Office make no pretense of independence.[216]

Apure is not likely to be an exception. A reliable media investigation indicates that over 90 percent of the 71 judges in the state do not have permanent positions, which makes them very vulnerable to political pressure.[217]

Secondly, victims of abuse by armed groups rarely report their crimes due to fear of retaliation and a perception that their complaints will be futile. [218] “Unfortunately, fear rules in [Apure],” a local human rights activist told Human Rights Watch, “no one says anything, no one knows anything.”[219]

Finally, even if people wanted to report crimes, the justice system in Apure is concentrated in cities such as Guasdualito and San Fernando, making access to justice difficult for many victims of abuse that are not close to locations where judicial authorities are available.[220]

Given these difficulties, many people in Apure, as in Arauca, go to the armed groups to have their problems “resolved.”[221] One resident told Human Rights Watch that authorities in Guasdualito told a relative in 2015 to go to armed groups to have her situation of domestic violence solved.[222] “That happens almost daily, with issues of fighting in bars, with family issues, with issues of domestic violence, with robbery of motorcycles,” he told Human Rights Watch. “They [the authorities] immediately send you there [with the armed groups], because they are the ones who address those issues.”

The Context in Which Armed Groups Operate

Arauca Province and Apure State

A 420-kilometer international border separates Colombia’s Arauca province from Venezuela’s Apure state. A river for most of its length, the border is extremely porous, enabling irregular migration as well as abuses because the perpetrators can cross the border without being questioned.[223] While there is one official border crossing to Venezuela from Arauca—the José Antonio Páez bridge in Arauca City—there are more than 50 informal points to cross the border.[224]

Arauca is home to about 240,000 people, who live in seven municipalities: Arauca City (the provincial capital), Arauquita, Cravo Norte, Fortúl, Puerto Rondón, Saravena, and Tame.[225]

A large part of the population in Arauca suffers from poverty, especially in rural areas. Around 36 percent face unmet basic needs, according to the most recent available data, from 2011; in the countryside, this number is around 64 percent.[226] In rural Arauca, just under one-third of the population lives in extreme poverty.[227]

Oil production is extremely important for Arauca. The Caño-Limón oil field in the province was decisive in Colombia’s ability to export oil in the 1980s and 1990s.[228] As of 2018, oil production represented 39 percent of the province’s gross domestic product.[229] The Caño-Limón oil pipeline, which connects the oil field with Colombia’s main port for oil exports in Coveñas, on the Atlantic coast,[230] begins in Arauca, and has been a constant target of guerrilla attacks.[231]

Almost 460,000 people live in Apure, according to the latest official figures, from 2011.[232] The province is divided into seven municipalities: San Fernando (the provincial capital), Achaguas, Biruaca, Muñoz, Páez, Pedro Camejo, and Rómulo Gallegos. Historically, Apure has been one of Venezuela’s poorest provinces.[233] Its economy is mainly agricultural, and cattle-raising is the principal economic activity.[234]

Armed Conflicts and Violence in Arauca and Apure

Two armed groups operate in Arauca: the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Martín Villa 10th Front FARC dissident group. These two groups, as well as the FPLN, operate in Apure.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported in December 2018 that the conflict between the ELN and the Colombian government is a non-international armed conflict under international humanitarian law.[235] The ICRC has not made a public determination as to whether the FARC dissident group operating in Arauca is party to an armed conflict.[236] Whether or not the FARC dissident group is also a party to the conflict depends on the extent to which it is genuinely linked through hierarchical relationships or certain types of cooperation with other parties to the conflict in Colombia.[237]

Human Rights Watch has not reached a determination that fighting in Apure amounts to a non-international armed conflict. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, so far, no reliable humanitarian or academic institution has made such determination publicly.[238]

National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN)

The ELN was founded in 1964 in northeastern Colombia by a small group of students. It has a left-wing ideology based on socialism with a strong influence of liberation theology. The group no longer looks to overthrow the Colombian government but instead claims to implement a strategy of “armed resistance” against the state and multinational corporations.[239]

In February 2017, the government of then-President Juan Manuel Santos and the ELN began formal peace talks in Quito, Ecuador. Colombian president Iván Duque suspended those peace talks indefinitely after the ELN took responsibility for a car-bombing in Bogotá in January 2019 that killed 22 police cadets.[240]