(Jakarta) - At least 18 Papuans are serving sentences in Indonesian jails simply for peaceful acts of freedom of expression and opinion, Human Rights Watch said in a new report released today. Such imprisonment violates international law and Indonesia’s international legal obligations.

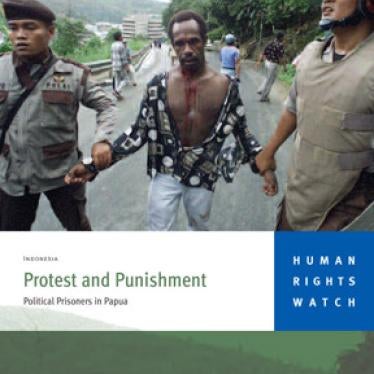

The 42-page report, “Protest and Punishment: Political Prisoners in Papua,” documents how the Indonesian government continues to use the criminal law to punish individuals who peacefully advocate for independence in the eastern Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Irian Jaya (hereafter referred to as Papua). All the prisoners have been convicted for treason or spreading hatred against the government, for nonviolent activities such as flag-raising, or attendance at peaceful meetings on self-determination options for Papua.

“Indonesia claims to have become a democracy, but democracies don’t put people in prison for peaceful expression,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Real freedom of expression, assembly and association are still in short supply for political activists in Papua.”

In June 2000, Linus Hiluka was charged with treason against the state and spreading hatred for his association with an independence organization, the Baliem Papua Panel, which is accused of being a separatist organization trying to destroy Indonesia’s territorial integrity and commit crimes against the security of the state. At no point was Hiluka accused of any violent or criminal activity. But he was convicted and sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment.

On May 26, 2005, Filep Karma and Yusak Pakage were found guilty of rebellion and spreading hatred against the government for the organization of peaceful celebrations on December 1, 2004 to mark Papua’s national day. For these acts, they were sentenced to 15 years’ and 10 years’ imprisonment respectively.

In “Protest and Punishment,” Human Rights Watch only included cases where the defendant was convicted for peaceful expression. There are many other cases in Papua where individuals have been charged with or convicted of crimes against the security of the state where it was alleged that the defendant engaged in or advocated violence. Human Rights Watch did not include these cases in the report, even those cases where the allegations of violent activity or advocacy did not appear to be readily supported by the evidence.

Human Rights Watch also pointed out that severe government-imposed restrictions on access to Papua mean that it is difficult to identify all such cases or to ascertain the full extent of the human rights situation in Papua.

“Until Papua is opened fully to scrutiny there will be doubt and confusion about the extent of abuse there,” said Adams. “As we saw in Aceh, closed conditions create breeding grounds for unchecked abuse. If the government has nothing to hide, it should open Papua to the outside world.”

The courts in Papua have played a negative role in decisions regarding cases of treason or spreading hatred. In almost every single case documented in the report, the courts handed down sentences harsher than those sought by the prosecution, notwithstanding that the “offenses” of the defendants were acts of legitimate peaceful political expression.

“The judiciary isn’t acting independently and isn’t throwing out cases that are clearly political in nature,” said Adams. “Instead of upholding individual rights, the courts are being used as a tool in political repression.”

Human Rights Watch called on the Indonesian government to immediately release all political prisoners in Papua and to drop any outstanding charges against individuals awaiting trial. Human Rights Watch also urged the government to repeal the vague and broad laws criminalizing the spreading of “hatred” and treason to ensure that no further prosecutions can take place in violation of international law. For many years, Human Rights Watch has called for the amendment of the Indonesian Criminal Code to conform with international law in order to protect basic freedoms of expression, assembly and association.

In 2006, Indonesia secured membership of both the United Nations Human Rights Council and the UN Security Council. It also acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. These are signs that Indonesia wants to be accepted as a rights-respecting member of the international community.

“The repression detailed in this report shows Indonesia still has a long way to go in guaranteeing real protections for basic human rights,” said Adams. “There is a clear gap between Indonesia’s international commitments and rhetoric and the reality on the ground.”